By Dave McCracken

You never really know what might lurk deep down in the depths of a muddy, tropical river…

This story is dedicated to my long-time loyal friend and fellow adventurer, Ernie Pierce. Ernie and I did three prospecting trips to Madagascar together, of which this is just one of the stories. He played a very important part on this project in working out how to increase fine gold recovery when processing heavy sands through standard riffles within the sluice box of a suction dredge. Ernie has an enthusiastic, magic disposition for being able to work out solutions to challenging problems in the field. He also overcame the primordial fear that every human being has of going down into deep, black underwater holes (where dangerous monsters lurk, if only in your imagination). I don’t know very many people who are willing to do that! It has been one of my greatest pleasures, and it has been a personal honor, to participate in adventures alongside of Ernie in California, and in multiple other interesting places all around the world.

It was difficult to see into the deep canyon, because it dropped off so steeply, and because the driver was veering around the bends in the road so fast, racing the Toyota Land Cruiser down the mountain road. This road had no guard rails to prevent us from plunging a thousand feet into the abyss. So, while I would like to have taken a better look at the breath-taking scenery, and I should have captured this part of the adventure with my video camera, all of my personal attention was riveted on the bumpy, narrow, winding road in front of us. I was scared that we were going to fly out over the edge to a certain and violent end! Once in a while, though, I did get a glimpse of a large river cascading down a steady series of natural falls. What an wonderfully-spectacular place! And I did manage to capture the incredible, wild river in the following video segment at one place where we stopped for a moment so I could relieve myself:

It was difficult to see into the deep canyon, because it dropped off so steeply, and because the driver was veering around the bends in the road so fast, racing the Toyota Land Cruiser down the mountain road. This road had no guard rails to prevent us from plunging a thousand feet into the abyss. So, while I would like to have taken a better look at the breath-taking scenery, and I should have captured this part of the adventure with my video camera, all of my personal attention was riveted on the bumpy, narrow, winding road in front of us. I was scared that we were going to fly out over the edge to a certain and violent end! Once in a while, though, I did get a glimpse of a large river cascading down a steady series of natural falls. What an wonderfully-spectacular place! And I did manage to capture the incredible, wild river in the following video segment at one place where we stopped for a moment so I could relieve myself:

The traffic obstacles that posed the most serious threat to our safety were the pain-stakingly slow, and what appeared to be an endless procession, of supply trucks that were inching their way up and down this very steep grade, taking advantage of the lowest gear they had, to save their brakes, those that even had breaks! Our driver, as did all the other drivers of the smaller vehicles moving in both directions, had the hair-raising

challenge of passing the slower vehicles without running into something coming from the other direction. One blind curve after the next placed us almost entirely in the hands of fate. Our driver had no way of knowing whether a vehicle was or was not coming from the other direction, as he committed our vehicle to many of the “go-for-it” passes that we made.

I was holding on for dear life!

I was holding on for dear life!

Madagascar was colonized by the French, so driving is done on the right side of the road. Being on the right side of the road put us dangerously-close to the precipice! At the high speed we were traveling, I was certain my time had finally come this late afternoon! On several occasions, by my calculations, there was no possible way that we were going to make it around the next curve! There just wasn’t enough room on the road to get past oncoming traffic without our wheels slipping over the edge of a very deep canyon. I couldn’t even see the canyon’s bottom! Each “go-for-it-pass” succeeded, either by divine intervention, or by the incredible driving ability of the young Malgasy man at the wheel.

I have lived a pretty gifted life, and I find myself counting my blessings pretty often. It’s not that very much was given to me; I have pretty-much had to climb the painful ladder of success several times. The end-result is all the more sweet when you have to work hard and sacrifice greatly to get there. I have lived on the cutting edge of danger a good part of the time; this is really true! There are not that many more things I feel I need to do before I meet my end of this life. So I find myself saying every once in a while that when the time comes, I am ready to move on to whatever is next. A lot of people say they/we are not scared to die. And you really feel that way when you are saying it! But we only feel that way when we are not looking death right in the eye! When sudden death lurks near, I feel the terror just like anyone else!

As quickly as the hair-raising ride began, we suddenly found ourselves safe at the bottom of the mountain. The immediate danger was over. We were graciously treated to a hot meal and a comfortable bed in the best (and only) hotel in the small village located at the base of the mountain. It was great to still be alive!

This was my fourth expedition to Madagascar in search of gold. Madagascar is the world’s fourth largest island. It is located about 400 miles off the south-east coast of mainland Africa. The country is approximately 1,200 miles long by 400 miles wide (at its longest and widest points). So it is no small country. The country is extremely poor, one of the poorest nations on earth. It is also extremely rich in mineral wealth. Especially in precious stones! Madagascar is an incredibly beautiful and scenic country! For the most part, the country is nearly undeveloped. Although, there are some larger towns that are quite developed. I captured the following video segment in the capital city of Antananarivo, a place where I have spent quite a lot of time:

This was my fourth expedition to Madagascar in search of gold. Madagascar is the world’s fourth largest island. It is located about 400 miles off the south-east coast of mainland Africa. The country is approximately 1,200 miles long by 400 miles wide (at its longest and widest points). So it is no small country. The country is extremely poor, one of the poorest nations on earth. It is also extremely rich in mineral wealth. Especially in precious stones! Madagascar is an incredibly beautiful and scenic country! For the most part, the country is nearly undeveloped. Although, there are some larger towns that are quite developed. I captured the following video segment in the capital city of Antananarivo, a place where I have spent quite a lot of time:

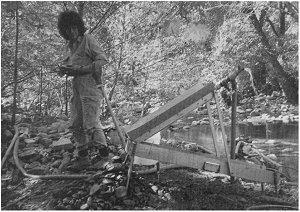

This preliminary dredge sampling program was on behalf of clients who own some gold mineral concessions in Madagascar. Ernie Pierce was along to assist with the sampling. We were there to get a preliminary idea of how much gold we could recover using suction dredges on two large rivers. We already knew gold was there because of an earlier expedition that we made into both locations to do a preliminary evaluation. Local gold miners were mining gold all over the place. They were mostly panning river gravel alongside the active river. Some were shoveling gravel from the active waterway in the shallow areas. Others were shoveling deeper-water areas out of dug-out boats, using the longest-handled shovels I have ever seen. The native miners were getting gold from everywhere!

This preliminary dredge sampling program was on behalf of clients who own some gold mineral concessions in Madagascar. Ernie Pierce was along to assist with the sampling. We were there to get a preliminary idea of how much gold we could recover using suction dredges on two large rivers. We already knew gold was there because of an earlier expedition that we made into both locations to do a preliminary evaluation. Local gold miners were mining gold all over the place. They were mostly panning river gravel alongside the active river. Some were shoveling gravel from the active waterway in the shallow areas. Others were shoveling deeper-water areas out of dug-out boats, using the longest-handled shovels I have ever seen. The native miners were getting gold from everywhere!

As this area was accessible by road, the logistics for setting up a dredging project were not too bad. We arrived with a substantial contingent of people and equipment. We had enough support to move us around, set up our camps, cook for us, do laundry and take care of all our basic needs.

As this area was accessible by road, the logistics for setting up a dredging project were not too bad. We arrived with a substantial contingent of people and equipment. We had enough support to move us around, set up our camps, cook for us, do laundry and take care of all our basic needs.

The company we were working for had quite a substantial base camp located where the end of the road met this river. There was a mess hall, some hot showers, individual bungalows; all the comforts of home! Unfortunately, the river near to and downstream of the base camp appeared to have deep sand deposits everywhere. There was no bedrock showing anywhere along that part of the river. Our initial impression was that the sand deposits in that lower section of river were going to be too deep to penetrate using our 5-inch sampling dredge. So we made a plan to pack all of our sampling gear and a fly camp (only basic needs) several kilometers upstream where the streambed deposits were shallow to bedrock. Our intention was to float down river, dredging sample holes through the entire distance back to the base camp.

After initially settling into our fly camp, the primary task at hand was for Ernie and I to determine whether or not the gold here was present in sufficient quantities (over a large enough area) to justify a production dredging program on this river. Ernie captured the following video sequence showing myself, Sam Speerstra (project manager) and Jack (Malagasy manager of our local support team) finalizing a sample plan after our camp was set up alongside the first river:

We spent the better part of a rather uneventful week dredging sample holes on this first river. Interestingly, while local miners were supporting their villages panning gold from placer deposits alongside the river, we could not find any high-grade gold deposits inside the active waterway. Ernie and I devoted long hours to making sizable excavations through hard-packed streambed material to bedrock. And while there was some amount of gold present everywhere, we could find no places where gold concentrated enough to justify any type of production dredging program. While we could speculate about the reasons why, the important thing was that we ruled out the possibility of a commercial dredging program in this area. This was what we went there to do. End of story!

As we did not bring anything extra with us when we packed our gear into the upper area of this river, I was not able to capture video until we arrived back down near the base camp. The video link just above includes a sequence that I took while we were dredging the final sample in front of the base camp. See how deep the light sand and gravel deposits appear to be? We did not expect to find the bottom of this loose streambed material, and we didn’t. But our sampling plan required that we at least try in several areas.

After spending a week on the first river, we were eager to relocate ourselves and our sampling infrastructure over to the second river that we intended to sample, which was several hundred miles away. That process took several days to accomplish. Prospects for commercial dredging opportunity on the second river looked much better to us during the earlier preliminary evaluation. We decided to save this area for last so we could devote most of our time there.

Normally, the first thing we do before making a sampling plan on a new section of river is walk, boat and/or swim the entire length if we can, to see what is there. This allows us to look everything over to see where the best opportunities appear to be. If lucky, we will come upon local mining operations. Those will communicate a lot to us about the prospects. This is because local miners, having spent generations prospecting for gold in the area, will already have a good idea where the best potential opportunities are for the type of mining that we do.

The following video segment found us making a plan on the first morning after we arrived at this second river. The person talking is Sam Speerstra:

Note the active shoveling operations in the river behind where we were pulling the dredge upriver.

How clear is the water?

The first and most important fact of note about the second river was that it was flowing with muddy water. Too bad! Water clarity is the first thing I look for when evaluating a river for dredging. Will I be able to see anything when I get on the bottom of the river? The answer in this case was an emphatic “NO!” This was pretty disappointing to me, because I had been assured by Sam months before, when we proposed the sampling program, that I could depend upon having clear water in this river. As it turns out, this particular waterway drains many thousand acres of upstream rice paddies. It never runs clear!

This was not Sam’s fault. It is nearly certain that you are going to get wrong information from locals in these types of places. With the help of even the best interpreters, communication and understanding tends to break down on technical things. What is clear water to me, and what is clear water to a rice farmer in remote Madagascar, are sure to be widely-different perceptions of reality. Especially when he has never even seen a face mask or a diver before! Over time, on the important things, I have learned to keep asking the same question over and over again in different ways. In doing so, it never ceases to amaze me how many different answers we come up with! Sometimes, no matter how many different ways you pose the questions, you can still never arrive at an answer that you have much faith in. This is not because the locals are lying. It is usually because their perception of the world is so vastly different than ours.

You have to be pretty flexible when conditions turn out not to be the way you expected them to be…

Sam Speerstra is the modern incarnation of “Indiana Jones.”

Sam Speerstra is the true-life incarnation of “Indiana Jones.” Sam has gotten me into and out of more (mis)adventures than anyone should experience in a single lifetime. The last dirty river Sam had me diving in was full of crocodiles and electric eels. That river was a nightmarish diamond project in Venezuela.

Without visibility, there was no way of knowing for certain what was on the bottom of this deep river! I’m not talking about the gold; we can figure that out through careful sampling. I’m talking about the critters!

When I initially evaluate a tropical river for a potential dredging project, the second condition that I evaluate after water clarity is whether or not there are life forms present that are potentially dangerous to me or my helpers. I do this mainly by visual observation. First, I look to see if the local people are working, washing, bathing and swimming in the water. If they are, and they appear healthy; I generally assume that the river is alright to dive in. Although, locals always have a stronger resistance to higher levels of bacteria in their local rivers. So our standard medicine kit on these projects always contains a supply of the best antibiotics to prevent serious types of internal or external infections.

I also ask the locals about sickness and dangerous critters. However, the problem with asking about critters in the water lies with the interpretation. You cannot depend upon only one inquiry or interpretation. For instance, I will never forget the size of the alligator I saw along a river in Borneo several years ago. This was after assurances from our local jungle-guides that alligators did not even exist there. We had been dredging the river several weeks when I suddenly encountered an alligator which must have been 18 feet long! It turned out that these man-eaters were being called “dragons” (not alligators) by the local village people! So I have learned to frame the most important questions in numerous different ways, and I keep asking them over and over again to different locals as I am trying to find things out about a new area.

A lot of local natives were in the river where Ernie and I wanted to sample, so it was probably safe — at least in the shallow portion. You never really know what might lurk deep down in the depths of a muddy, tropical river…

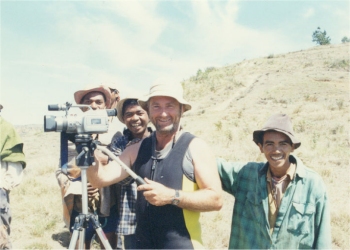

Ernie and his team capturing a little video…

Ernie and his team capturing a little video…

I have accomplished quite a few dredge sampling projects in dirty water. It is a very scary and difficult business. The work involves going down into deep, pitch-dark, frightening places “in the blind,” with no visual assistance. I know that there are live creatures down there that do not appreciate my intrusion into their territory (unless they intend to eat me). To move around cautiously, I have to feel my way by sticking my hand or foot out into complete darkness, feeling around for what is there. Most of the time, before going down, I don’t even know how deep the water is. Sometimes I have to find out by shimmying down the suction hose, reaching out tentatively with one leg at a time to see if I can touch bottom. I am in a state of heightened awareness, desperately hoping that I am not going to touch something that is big and alive. All the while, I am wondering, “How far am I going to have to go this time?”

It is one thing to read about this in the comfort of your computer within a safe environment and feel like you can do it. But you are not exactly the same person when you are dangling dangerously in the dark. You might be the same basic identity; but other parts of you (like terror) get switched on at full volume. I suppose you would really have to go through the experience to fully-appreciate it. Until you do; take it from someone who is used to living on the edge: Diving down in deep, muddy, tropical rivers is not easy!

Muddy water creates total darkness about three feet beneath the water’s surface, sometimes less. So, all you can see down there is what is in your imagination. Do you remember those terrifying nightmares that you had when you were a kid? They still lurk in your subconscious. When going down into deep, dark, terrifying physical places, memories of nightmarish dreams are brought immediately back to life. If you are someone who doesn’t think you are afraid of anything, you ought to try diving in deep, muddy, tropical rivers! You will find there that your deepest fears are just below the surface of your normal, everyday life.

Let me try this a different way: Do you know that feeling when someone startles you at just the right (wrong) time and frightens the heck out of you? Just for that split second, you feel a deeply-seated fear; right on the edge of a panic attack? That is exactly what you experience when you go down into the deep darkness of a tropical river; especially on the first dive.

Nevertheless, over time, I have learned to deal with dirty water. This does not mean that I am not still afraid. I am! It means that I have worked out a way to proceed. Dredging in dirty water is a much slower process. Everything must be done by blind feel, and therefore with care. The process is all about taking control over a single space in the darkness. You get to know every rock in the hole and every obstruction which defines the space. Sometimes, there are submerged trees or other obstacles that you must be very careful around to prevent your airline from becoming snagged. You must dredge alone in dirty water. Otherwise, you cannot toss rocks or roll boulders out of the excavation without a good chance of hurting someone else down there that you cannot even see.

Base camp

Several years ago, my lead diver on a dirty-water sampling operation in Cambodia had a portion of his ear bitten off by a fish. One quick bite and it was gone! That created lots of blood and drama to slow the job down! After that, none of the other guys that I had brought with me wanted to dive. Who could blame them? But we still needed to complete the job; that’s what we do! Surprisingly, it was the lead diver who had to continue the diving on that particular job. I did a little, too; but, that was mainly to show the other guys that I would not ask them to do something which I personally was not willing to do. We wore full dive hoods and dive helmets to protect ourselves from the biting fish, whatever it was. We never saw the creature that took the bite! And as it went, just a few more dives to finish the job proved-out one of the richest gold locations I have ever discovered. But underwater, we couldn’t see a thing!

The primary consideration in assessing a dirty river is how much more time we need to allow ourselves to get the job done in an underwater environment where the divers cannot see anything.

This is one main factor which nearly always undermines the commercial viability of a sizable dredging operation. Who is going to go down and run a 10-inch dredge in zero visibility, 6 hours a day, for a living? The gold deposits will have to be very rich to support this kind of program. I have found several underwater gold deposits that are moderately rich, but they are protected by dirty water conditions. The deposit that we found in Cambodia, for example, would make a dredging operation a lot of money if the diver-visibility problem could be overcome.

People often ask why we need to send divers down in the first place to conduct a gold dredging program. They want to know why the excavation cannot be managed from the surface using mechanical arms. The reason is that sizable rocks along the river-bottom must be moved out of the way of the suction nozzle. Otherwise, one oversized rock (too big to go up the nozzle) after another gets in front of the suction nozzle, blocking further progress until it is moved out of the way. Because of this, with few exceptions, there is no other effective way to proceed without putting divers down into the depths.

These two articles explain the underwater process in detail:

When Ernie and I first started watching the local gold miners on this particular river in Madagascar, we relaxed our fears; because even their small children were bathing and playing inside the river. This was a good break for us!

Now it was just a matter of deciding where to do our sample holes. Ernie and I used a two-pronged strategy that we have developed over the years for these situations. First, we dredge sample holes near and in line with where the local miners are actively achieving positive results. Most high-grade gold deposits follow a common line down along a waterway. For example, see how the following important video segment shows how the many local digging operations inside the river are following a common path. If you look closely, you can see tailings remaining from previous digging activity right on the same path. To get our own sampling operations off to a good start, we usually begin along the same path in the river where most of the local miners are working:

Secondly, Ernie and I offered financial rewards to the local miners for each place they showed us to dredge where we could find lots of gold. Such places are usually in the deeper areas where locals cannot gain access using the gear at their disposal. A “grande” reward goes to the person who shows us the place where we find the most gold. Wow, this incentive sure got Malagasy miners talking; and we started to find a lot of gold!

We moved our sample dredge in direct line with where local miners were doing well working out of dug-out canoes using long-handled shovels. This got us into rich gold right away!

Since we could not see how deep the water was in this dirty river, and because we had already established that there were some deep deposits of sand and loose gravel along the bottom that we wanted to avoid with our 5-inch dredge, before doing dredge samples, we used a long steel probe to find areas along the established gold path where the water was not too deep for us to reach bottom, and where we could reach hard-packed streambed without having to go through a deep layer of sand first. The following video segment shows how we performed this important pre-sampling process:

In one location, I decided to sample directly underneath a native “boat-mining” operation. I did this because I noticed the natives were working the location very aggressively. This is always a good sign! They were using long-handled shovels, about 20 feet long, from anchored boats well out into the river. The water was at least 12 feet deep! These shovels were especially designed to bring gravel up from deep water. The natives were very good at it. Have you ever tried shoveling material from underwater? Nearly all the material washes off the shovel before you can get it to the surface. Not with the Malagasy boat miners, however. They were bringing up full shovels every time. The material was being panned at the surface.

The following video segment provides a firsthand look and explanation of the boat-mining which we saw when we first arrived at this river. Seeing this type of active mining along the river by local miners was very encouraging, and immediately helped shape the sampling plan which Ernie and I would follow:

As it turned out, local miners from the boat-mining operations had plenty of gold to sell! They were anchoring their boats out in the river by driving hardwood poles deeply down into the streambed material, and then tying their boats off firmly to the poles at the water’s surface. The boats needed to remain stationary to allow the miners a firm platform from which to work the hard-packed streambed material along the bottom of the river. Consequently, we could look along the river and see many stakes remaining from earlier mining activity. Unsurprisingly, most of the stakes followed a common line down the river as far as we could see. We still needed to confirm it by sampling, but Ernie and I had a pretty good idea where the high-grade gold line was located in this river even before we unloaded our sample dredge from the truck. This was good!

The following video segment shows how we went about our sampling program. Notice the wooden poles out in the river? Because there was zero visibility underwater, you will see that Ernie had to keep jumping up to peak his head above water to steer himself and the dredge out in line with the poles. Where the water was too deep for that, we had to shimmy up the suction hose to have a look. Sometimes, it was so difficult to find our way in the dark, that we first positioned the dredge out on the river using ropes, and then shimmied down the suction hose in the dark to take a sample:

Ernie and I felt it was important to get one sample directly under one of the active boat-mining operations. This was so that our clients could estimate the value of gold deposits that local miners were developing in the river, and to see if they were excavating all the way to the bedrock. I was the one to dredge that particular sample. To accomplish this safely, we paid those particular boat-miners to stop digging for a few hours while I was under their boat.

As we had to drive our dredge out past the middle of the river to reach their hole on the bottom of the river, it was quite a challenge to find their hole in the pitch dark. When I finally found it, I was amazed to discover that they were actually penetrating deep into the hard-packed streambed material with their long-handled shovels. This must have presented them with a substantial challenge, because the cobbles were tightly interlocked together. At the bottom of their excavation, I found that their shovels were touching on bedrock, but that there was no way for them to take up the highest-grade material which was resting directly on bottom. They also were not able to clean the natural gold traps inside of the bedrock where most of the gold should have been. Too bad!

Being mindful that I was dredging in a high-grade deposit that had been previously located by other miners, I did not stay under the boat-miner platform any longer than it took to dredge up about a cubic meter of the hard-packed pay-dirt off the bottom. The material was only around four feet to bedrock; an easy place to dredge even in the dark water. We recovered a lot of gold proportionately to the volume of streambed that I processed. My estimation is that the river could produce 5 ounces of gold per day in dirty water using a 5-inch dredge.

The following video segment shows the gold we recovered from this sample, and captures my summation of what we needed to do to complete our preliminary sampling program on this part of the river:

The following video segment shows the gold we recovered from this sample, and captures my summation of what we needed to do to complete our preliminary sampling program on this part of the river:

The gravel being brought up from the river bottom by local miners was panning out very well!

As it turned out, the local miners were greatly impressed and worried by our dredging machine. They watched the volume of gravel wash across our sluice box, while they were bringing it up one small shovelful at a time. Prior to our arrival on the scene, they were the biggest and the best miners around! They could put two and two together, however. After our test under their boat, they began 24-hour boat-mining operations in that location. You could see their campfires down by the river (for light) burning all night long. Within a few days, there were a dozen boat-mining operations going full blast, 24 hours a day. They were worried we were going to return and dredge up all their gold. As good as their discovery was, we were not going to do that. Our sampling thrust thereafter was to determine if the high-grade streambed material extended downstream; and if so, how far?

There was certainly high-grade gold at the bottom of the river!

I’ll never forget Ernie’s first deep, dirty-water dredging dive. I could see that he was pretty nervous about taking the dive, so I offered to walk (crawl) him out into the river for the first time. He agreed to this. After everything was up and running, I took Ernie by the hand and crawled alongside of him in total darkness out to the middle of the river. It was a long way out to where Ernie was going to help finish the sample that I had already started. We grabbed onto the suction hose and dragged the dredge out into the middle of the river, instructing the dredge-tenders to allow the dredge to follow our bubbles. The water was about 12 feet deep in the middle of the river. I could tell that Ernie was having a difficult experience by the way he was gripping my hand. He was holding on for dear life! Finally, Ernie had enough and he began giving me the signal that he wanted to go back to the shore. I got the message immediately from the way he was grabbing me with both hands and jerking me toward the dredge. After we returned to the surface, Ernie told me that he was just “not up to it.” He had that look of panic in his eyes, a feeling I personally know very well! There is no use in trying to push anyone into doing something while they’re in a state of fear and panic. As I have said, it is not easy diving in dirty water! We all have a limit, beyond which we are not willing to go!

I’ll never forget Ernie’s first deep, dirty-water dredging dive. I could see that he was pretty nervous about taking the dive, so I offered to walk (crawl) him out into the river for the first time. He agreed to this. After everything was up and running, I took Ernie by the hand and crawled alongside of him in total darkness out to the middle of the river. It was a long way out to where Ernie was going to help finish the sample that I had already started. We grabbed onto the suction hose and dragged the dredge out into the middle of the river, instructing the dredge-tenders to allow the dredge to follow our bubbles. The water was about 12 feet deep in the middle of the river. I could tell that Ernie was having a difficult experience by the way he was gripping my hand. He was holding on for dear life! Finally, Ernie had enough and he began giving me the signal that he wanted to go back to the shore. I got the message immediately from the way he was grabbing me with both hands and jerking me toward the dredge. After we returned to the surface, Ernie told me that he was just “not up to it.” He had that look of panic in his eyes, a feeling I personally know very well! There is no use in trying to push anyone into doing something while they’re in a state of fear and panic. As I have said, it is not easy diving in dirty water! We all have a limit, beyond which we are not willing to go!

Instead, I urged Ernie to do some initial sampling in shallow water so he could get a feel for it. He could work standing up, with his head out of water, if he needed to. Ernie was up for this and immediately went to work closer to the shore. We needed to get some samples over there, anyway. A few minutes later, on his own determination, Ernie went bravely out into the middle of the river and was taking samples from the particular area where we really needed them; in line with where the locals were getting the most gold for their effort. Dirty water dredging is an experience you really have to ease into at your own pace. Ernie adapted quickly, and was soon working efficiently. I could tell this by the continuous gravel which was washing across the dredge’s sluice box.

Locals observing Ernie do a final clean-up

Each of us has our own personal limits. Would you walk a tight rope suspended a thousand feet in the air between two tall buildings? Most of us wouldn’t! What would it take to get you to do it?

It takes a lot of personal courage to go well beyond our normal comfort zone into the realm of personal terror. The type of work I do often allows me the opportunity to watch others confront their own personal limitations. In defining this particular character trait of an individual, it is unfair to make your judgment based upon where the initial limits are. True courage is tested when a person is confronted with the need to go beyond personal limits, no-matter where the limits are! I was very honored that day to be present when Ernie overcame very personal and serious fears, and went out into the middle of the river to help accomplish what we were there to do.

On one occasion, Ernie came up the suction hose in a real hurry! I saw the dredge bob up and down as he pulled himself up the suction hose. As it turns out, Ernie was walking around on the bottom of the river (total darkness), and he stepped off into a “bottomless hole”. When he got to the surface, Ernie said that it all had happened within a split second. He suddenly found himself dangling like fish bait from the end of the 20-foot suction hose directly over the “depths of hell.” Luckily, the weight of his body did not pull the suction hose free from the power-jet. I have had the same experience happen to me in dark water. So now, I am careful to take only small steps, feeling my way along the bottom slowly to avoid frightening surprises!

One of the most important things to do in any sampling program is test the efficiency of the recovery system that is being used. To do a proper job of it, you must establish how much of the target mineral (gold, gemstones or whatever) that your recovery system is not catching when processing the raw material from each sample. You cannot just assume the recovery system being used is providing 100% recovery. You have to make regular tests of your tailings using other recovery equipment that can provide the most accurate results possible. During a preliminary sampling program, this usually means careful panning of random tailing samples.

On this program, since we had plenty of very experienced local panners giving us support, whenever possible, we directed our dredge tailings over near the riverbank where our helpers could pan everything that passed over the dredge. They would then show us what we were losing from the dredge.

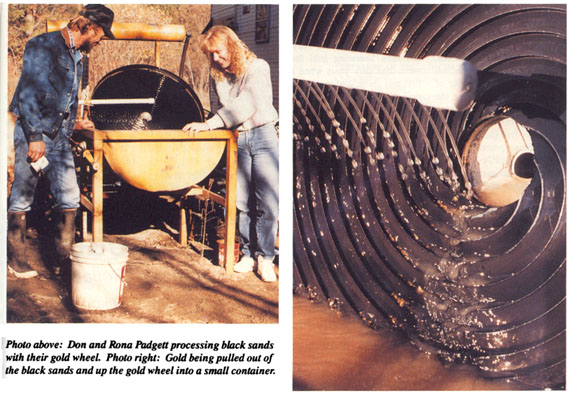

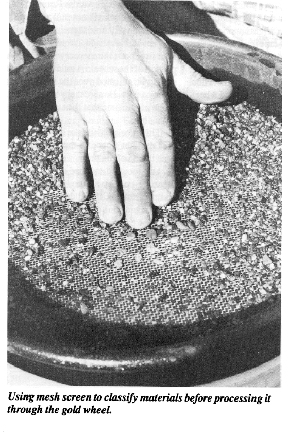

Since our most important samples were dredged out in deep water, Ernie and I ended up building a wooden box that we were able to suspend from its own floats and catch all the tailings from our dredge. After each sample was complete, while we processed the dredge concentrates through our special concentrator, local miners would carefully pan all our tailings for us.

As it turned out, our losses from the dredge initially were quite substantial. This river had a lot of fine-sized gold that was just passing through our recovery system into tailings with sand. Within the limitations of the tools we had available to us in the field, Ernie and I tried different ideas to improve the dredge’s recovery system. Ultimately, Ernie came to the conclusion that the classification screen needed to be raised further away from the riffles in our sluice box. This allowed more water flow to help the riffles to concentrate. Working this out in the field gave us important insight into what would be needed in the recovery system on a commercial dredge in that area.

The following video segment shows the process we were following to work out how to recover the substantial amount of fine gold we were finding in the river-bottom deposits on this river:

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy Gold Prospecting Equipment & Supplies.

- Books & Videos by this Author

- More Gold Mining Adventures

- More about Suction Dredging

- Different Kinds of Sampling

- Schedule of Events

Things were going good and looking better. Yesterday had been a long day, but not as long as I was able to work; about three and a half tanks of gasoline or seven hours. Today, as planned after the gold weigh-up last night, I was at the river early, determined to put in at least a four-tank day . . . and pull my first half-ounce of gold in a day!

Things were going good and looking better. Yesterday had been a long day, but not as long as I was able to work; about three and a half tanks of gasoline or seven hours. Today, as planned after the gold weigh-up last night, I was at the river early, determined to put in at least a four-tank day . . . and pull my first half-ounce of gold in a day!

Three months of planning, over a thousand miles of traveling, anticipation of

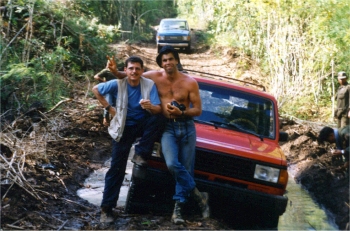

Three months of planning, over a thousand miles of traveling, anticipation of  The trip to Columbia was uneventful; but it was a very, very long drive. We finally arrived at the road which would lead us down to the river. As we descended, we saw ahead of us large billowing clouds of smoke coming over the mountain ridge. We could not believe that we had driven all this way and the mountain was on fire! This was

The trip to Columbia was uneventful; but it was a very, very long drive. We finally arrived at the road which would lead us down to the river. As we descended, we saw ahead of us large billowing clouds of smoke coming over the mountain ridge. We could not believe that we had driven all this way and the mountain was on fire! This was

A short time ago, my dredging partner and I were sampling in a new section of river. We were looking for

A short time ago, my dredging partner and I were sampling in a new section of river. We were looking for  This new section of river had slow water towards the bank. I had it figured that the pay-streak would be located out under the fast water — which is often the case. I don’t know why, but mother-nature often has a knack for hiding her natural treasures in areas which are more difficult to get into!

This new section of river had slow water towards the bank. I had it figured that the pay-streak would be located out under the fast water — which is often the case. I don’t know why, but mother-nature often has a knack for hiding her natural treasures in areas which are more difficult to get into! Having it in mind that the best gold would be further out into the current, I pushed the hole in that direction. The further I pushed, the more difficult it was. The bedrock out there showed no gold. My arms felt like spaghetti!

Having it in mind that the best gold would be further out into the current, I pushed the hole in that direction. The further I pushed, the more difficult it was. The bedrock out there showed no gold. My arms felt like spaghetti! If the streambed material had been deeper, it is likely I would not have tested toward the inside. Why? Because I had it in my mind that the pay-streak was out under the fast water; not under the slow water. But, because the streambed was shallow, and I had seen some gold on the bedrock where I first touched down, I decided to take a quick cut off the inside of the sample hole.

If the streambed material had been deeper, it is likely I would not have tested toward the inside. Why? Because I had it in my mind that the pay-streak was out under the fast water; not under the slow water. But, because the streambed was shallow, and I had seen some gold on the bedrock where I first touched down, I decided to take a quick cut off the inside of the sample hole. There is a lesson in this!

There is a lesson in this! The lesson is to never give up hope! Never say die! Sometimes, you will find that you are as close to winning as you can be, even though things have never looked worse. This is especially true in gold mining.

The lesson is to never give up hope! Never say die! Sometimes, you will find that you are as close to winning as you can be, even though things have never looked worse. This is especially true in gold mining. We manage

We manage  In many ways, this is not dissimilar to a person’s intention to accomplish a goal. Sometimes, we will find our immediate progress slowed down or stopped altogether. But if we maintain our intention, and study the barriers to our progress, we can usually find other ways to make progress. The key is in maintaining the intention, keep pushing along, and having a little patience.

In many ways, this is not dissimilar to a person’s intention to accomplish a goal. Sometimes, we will find our immediate progress slowed down or stopped altogether. But if we maintain our intention, and study the barriers to our progress, we can usually find other ways to make progress. The key is in maintaining the intention, keep pushing along, and having a little patience.

Author’s note: This story is dedicated to Alan Norton (“Alley”), the lead underwater mining specialist who participated in this project. Under near-impossible conditions, Alan made half of the key dives which enabled us to make this a very successful venture.

Author’s note: This story is dedicated to Alan Norton (“Alley”), the lead underwater mining specialist who participated in this project. Under near-impossible conditions, Alan made half of the key dives which enabled us to make this a very successful venture. The dual engine aircraft was

The dual engine aircraft was  It took about an hour to pack the airplane completely full of mining equipment. Since we had to remove the seats to make room for gear, Alley and I were directed to lay up on top of the gear that was stacked up in the belly of the plane. No seat belts! And the plane was loaded so heavily, even the pilot was not sure whether or not we were going to make it off the runway when we took off. We barely made it, and the plane was very sluggish to fly for the remainder of that trip.

It took about an hour to pack the airplane completely full of mining equipment. Since we had to remove the seats to make room for gear, Alley and I were directed to lay up on top of the gear that was stacked up in the belly of the plane. No seat belts! And the plane was loaded so heavily, even the pilot was not sure whether or not we were going to make it off the runway when we took off. We barely made it, and the plane was very sluggish to fly for the remainder of that trip. After quite some time, at a point when the clouds cleared away just long enough to see, Sam pointed down to a short runway cut out of the jungle. At first, we could not believe we truly were going to try and land there. Sure enough, it was the base camp for the concession. We made one low pass over it. The base camp looked large and well equipped. There was also a small local village right near the base camp. The landing strip was filled with puddles and looked to be mostly mud. Alley and I were a little nervous after Sam’s big buildup, and we had very good reason to be nervous.

After quite some time, at a point when the clouds cleared away just long enough to see, Sam pointed down to a short runway cut out of the jungle. At first, we could not believe we truly were going to try and land there. Sure enough, it was the base camp for the concession. We made one low pass over it. The base camp looked large and well equipped. There was also a small local village right near the base camp. The landing strip was filled with puddles and looked to be mostly mud. Alley and I were a little nervous after Sam’s big buildup, and we had very good reason to be nervous. Local villagers came out to help us unload the plane. They all seemed like very nice people. After having a chance to load our gear into the bungalow, Sam gave us a short tour of the base camp. The whole area was fenced in. There were numerous screened-in bungalows for the various crew member sleeping quarters, a large kitchen, an office, and a large screened-in workshop area. The company had spent a lot of money getting it all set up. There was a jeep and two off-road motorcycles—all in a poor state of repair. They operated, but without any brakes.

Local villagers came out to help us unload the plane. They all seemed like very nice people. After having a chance to load our gear into the bungalow, Sam gave us a short tour of the base camp. The whole area was fenced in. There were numerous screened-in bungalows for the various crew member sleeping quarters, a large kitchen, an office, and a large screened-in workshop area. The company had spent a lot of money getting it all set up. There was a jeep and two off-road motorcycles—all in a poor state of repair. They operated, but without any brakes. We met the chief, who looked totally wasted on something–probably the Cochili drink. And immediately upon our arrival, the chief ordered some children to bring glasses and drink for everyone. Promptly, our glasses were filled to the rims. Sam quickly downed his first glass, licked his lips, smiled and said, “This is all in the name of good local public relations!” To be polite, I downed half my glass and did my best to choke back my gag. The stuff tasted terrible! I realized my mistake right away when one of the kids immediately took my glass and refilled it to the brim. Alley was paying close attention and slowly sipped his drink, and I followed suit. There was no place to spit if out without being seen, so we had to drink it down. Sam put down three or four more glasses and shortly was slurring his Spanish in final negotiations with the chief. I’m not really sure they understood each other concerning any of the details, but everyone seemed happy with the negotiation.

We met the chief, who looked totally wasted on something–probably the Cochili drink. And immediately upon our arrival, the chief ordered some children to bring glasses and drink for everyone. Promptly, our glasses were filled to the rims. Sam quickly downed his first glass, licked his lips, smiled and said, “This is all in the name of good local public relations!” To be polite, I downed half my glass and did my best to choke back my gag. The stuff tasted terrible! I realized my mistake right away when one of the kids immediately took my glass and refilled it to the brim. Alley was paying close attention and slowly sipped his drink, and I followed suit. There was no place to spit if out without being seen, so we had to drink it down. Sam put down three or four more glasses and shortly was slurring his Spanish in final negotiations with the chief. I’m not really sure they understood each other concerning any of the details, but everyone seemed happy with the negotiation. One very interesting thing about this jungle is that huge trees, for no apparent reason at all, come crashing down. At least several times a day, we would hear huge trees crashing down in a deafening roar. On one occasion, Alan and I were returning to base camp on the jeep trail. We had just come up that trail fifteen minutes before. As we were going down a muddy hill and rounding a bend, we ran smack right into a huge tree which had just fallen across the trail. Good thing I was driving! We smashed into the tree with both of us flying off the bike. Luckily, neither of us were hurt more than just a few bumps and bruises, although the front-end of the motorcycle was damaged. Chalk up one more for the jungle.

One very interesting thing about this jungle is that huge trees, for no apparent reason at all, come crashing down. At least several times a day, we would hear huge trees crashing down in a deafening roar. On one occasion, Alan and I were returning to base camp on the jeep trail. We had just come up that trail fifteen minutes before. As we were going down a muddy hill and rounding a bend, we ran smack right into a huge tree which had just fallen across the trail. Good thing I was driving! We smashed into the tree with both of us flying off the bike. Luckily, neither of us were hurt more than just a few bumps and bruises, although the front-end of the motorcycle was damaged. Chalk up one more for the jungle. We had a three hundred-foot roll of half-inch nylon rope with us for the mining operation. The following day, Alley and I allocated one hundred and fifty feet of that rope to be used to tie our cots up into the shelter beams to keep us well away from the ground. Our Indian guides were quite amused by this. The rest of the rope was used in the dredging operation.

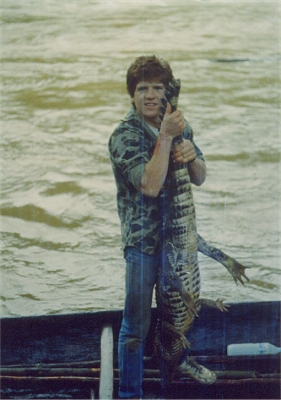

We had a three hundred-foot roll of half-inch nylon rope with us for the mining operation. The following day, Alley and I allocated one hundred and fifty feet of that rope to be used to tie our cots up into the shelter beams to keep us well away from the ground. Our Indian guides were quite amused by this. The rest of the rope was used in the dredging operation. On top of that, the natives caught a hundred-pound Cayman (alligator) with a net out of one of our dredge holes where they had been fishing. It was certainly big enough to take a man’s arm off. At that point, the natives told us these animals came much larger on the river.

On top of that, the natives caught a hundred-pound Cayman (alligator) with a net out of one of our dredge holes where they had been fishing. It was certainly big enough to take a man’s arm off. At that point, the natives told us these animals came much larger on the river. The diving was extremely dangerous. Each time one of us went down, we did so knowing there was a definite possibility that we would not live through it. The only other option was to

The diving was extremely dangerous. Each time one of us went down, we did so knowing there was a definite possibility that we would not live through it. The only other option was to  Our main native guide was named Emilio. He was a real jungle man in every sense of the word. He walked with a limp because of an earlier airplane crash in which he was the sole survivor. His family hut had been hit by lightning several years before, and everyone in the hut was killed except Emilio. He was a real survivor! One night, he went hunting with our shotgun–which was only loaded with a single round of light bird shot. In the darkness of the jungle at three o’clock in the morning, Emilio snuck right up on a five-hundred pound female wild boar and shot it dead–right in the head. We had good meat for several days, and even the disgruntled cook cooperated with some excellent meals.

Our main native guide was named Emilio. He was a real jungle man in every sense of the word. He walked with a limp because of an earlier airplane crash in which he was the sole survivor. His family hut had been hit by lightning several years before, and everyone in the hut was killed except Emilio. He was a real survivor! One night, he went hunting with our shotgun–which was only loaded with a single round of light bird shot. In the darkness of the jungle at three o’clock in the morning, Emilio snuck right up on a five-hundred pound female wild boar and shot it dead–right in the head. We had good meat for several days, and even the disgruntled cook cooperated with some excellent meals.

canoes over top of submerged logs and through rapids. A lot of the time the boats were loaded so heavily that there was only about a half-inch of freeboard on each side. Yet, we never swamped a boat.

canoes over top of submerged logs and through rapids. A lot of the time the boats were loaded so heavily that there was only about a half-inch of freeboard on each side. Yet, we never swamped a boat. While we were hauling our gear along the mile and a half-long trail to the landing strip, I was swarmed by African killer bees. It was terrifying! I heard them coming from quite some distance away. It sounded like a bus coming through the jungle. First, there were only a few bees around me, then a whole bunch. In panic, I was running down the trail at full speed like a mad man out of control, swinging my hat about. Then they were gone. I put my hat back on only to get stung right on top of the head. I felt completely spent. It was time to go home.

While we were hauling our gear along the mile and a half-long trail to the landing strip, I was swarmed by African killer bees. It was terrifying! I heard them coming from quite some distance away. It sounded like a bus coming through the jungle. First, there were only a few bees around me, then a whole bunch. In panic, I was running down the trail at full speed like a mad man out of control, swinging my hat about. Then they were gone. I put my hat back on only to get stung right on top of the head. I felt completely spent. It was time to go home. It is common knowledge that if one is both wealthy and strange, he or she is called eccentric. Most miners I have run across are not wealthy, but the word eccentric suits them very well.

It is common knowledge that if one is both wealthy and strange, he or she is called eccentric. Most miners I have run across are not wealthy, but the word eccentric suits them very well. One evening in the same area, the bears came across the river and tore up the campsite of another miner while looking for their dinner. They ate all the fresh fruit, eggs and meat (except for the bologna) and other packaged sandwich meat. They also left the white bread. Perhaps we can learn something from these bears!

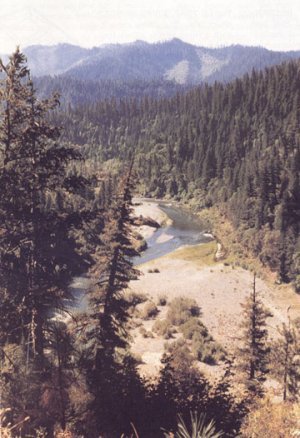

One evening in the same area, the bears came across the river and tore up the campsite of another miner while looking for their dinner. They ate all the fresh fruit, eggs and meat (except for the bologna) and other packaged sandwich meat. They also left the white bread. Perhaps we can learn something from these bears! He told me as he was walking along the road in an unhurried fashion, an osprey suddenly flew from his nest and began calling to him. As the miner looked up, he thought, “What a magnificent creature you are and what beautiful feathers you have.” He was trying to imagine the view the bird would have 300 feet above the river. The miner’s view was almost overwhelming in its beauty, and he was only 100 feet or so above the river. With that, the bird continued to call the miner, flapped its wings with great force and seemed to stop in midair. From the bird, a perfect feather fell landing near where the miner stood. The feather is carefully and lovingly displayed in the miner’s home as a memento. He says it is a gift from “one of God’s creatures.”

He told me as he was walking along the road in an unhurried fashion, an osprey suddenly flew from his nest and began calling to him. As the miner looked up, he thought, “What a magnificent creature you are and what beautiful feathers you have.” He was trying to imagine the view the bird would have 300 feet above the river. The miner’s view was almost overwhelming in its beauty, and he was only 100 feet or so above the river. With that, the bird continued to call the miner, flapped its wings with great force and seemed to stop in midair. From the bird, a perfect feather fell landing near where the miner stood. The feather is carefully and lovingly displayed in the miner’s home as a memento. He says it is a gift from “one of God’s creatures.”

If one were to ask a miner about an Entosphenus tridentatus or an Ocorhynhus Kisutch or a Salmo Gairdneri, he would probably not be able to tell you these are a Pacific Lamprey, a Silver Salmon or a Steelhead Rainbow Trout in that order. Nevertheless, there is a working arrangement between the miner and the creatures of the river.

If one were to ask a miner about an Entosphenus tridentatus or an Ocorhynhus Kisutch or a Salmo Gairdneri, he would probably not be able to tell you these are a Pacific Lamprey, a Silver Salmon or a Steelhead Rainbow Trout in that order. Nevertheless, there is a working arrangement between the miner and the creatures of the river.

The meaning of “Good Gold” is a matter of perspective and experience. This phrase is generally used in terms of quantity and ease of extraction. A couple of old-timers, sitting around the fire talking gold, will often have enough shared-experiences to know what the other means by “good.”

The meaning of “Good Gold” is a matter of perspective and experience. This phrase is generally used in terms of quantity and ease of extraction. A couple of old-timers, sitting around the fire talking gold, will often have enough shared-experiences to know what the other means by “good.” Building a workable dry-washer would be a snap. I have always been good at figuring out how machines work and how they should be constructed. Ten minutes with a friends’ bellows dry-washer was enough to get me started on our own machine. A few days later, we were packed and driving to the desert with our newly-built dry-washer and an old 3-horsepower Briggs and Stratton engine. I just had to test my new creation. When it comes to gold, to me,

Building a workable dry-washer would be a snap. I have always been good at figuring out how machines work and how they should be constructed. Ten minutes with a friends’ bellows dry-washer was enough to get me started on our own machine. A few days later, we were packed and driving to the desert with our newly-built dry-washer and an old 3-horsepower Briggs and Stratton engine. I just had to test my new creation. When it comes to gold, to me,

Successful mining in streambeds is generally accomplished in two steps: (1)

Successful mining in streambeds is generally accomplished in two steps: (1)

When hard-packed streambed is being mined, the cobbles and boulders (i.e., rocks that are too large to pass through the recovery system) are tossed back onto a pile behind the production area. As the production area moves forward, piles of boulders and cobbles are left behind in place of the original hard-packed streambed. Sometimes, sand, silt and gravel that is processed through the recovery system is dropped on top of the cobbles. Later, winter storms also wash sand, silt and gravel across the top of the cobbles. The sand, silt and light gravel then filters down and fills in most of the space between the cobbles. Therefore, tailings usually end up as loose stacks of cobbles with sand, silt or light gravel filling the spaces.

When hard-packed streambed is being mined, the cobbles and boulders (i.e., rocks that are too large to pass through the recovery system) are tossed back onto a pile behind the production area. As the production area moves forward, piles of boulders and cobbles are left behind in place of the original hard-packed streambed. Sometimes, sand, silt and gravel that is processed through the recovery system is dropped on top of the cobbles. Later, winter storms also wash sand, silt and gravel across the top of the cobbles. The sand, silt and light gravel then filters down and fills in most of the space between the cobbles. Therefore, tailings usually end up as loose stacks of cobbles with sand, silt or light gravel filling the spaces.

One group of early miners, approximately eighteen men, traveled the millennia-old foot-trails of the Karuk people, up to a place of broad gravel bars and exposed bedrock two miles upstream from Clear Creek. For thousands of years the Karuk Indians lived along the river on similar “flat” campgrounds, ancient gold-bearing deposits of river gravel!

One group of early miners, approximately eighteen men, traveled the millennia-old foot-trails of the Karuk people, up to a place of broad gravel bars and exposed bedrock two miles upstream from Clear Creek. For thousands of years the Karuk Indians lived along the river on similar “flat” campgrounds, ancient gold-bearing deposits of river gravel!