BY MICHAEL WARREN

The Oak of the Golden Dream sits beside a quiet stream in what is now known as Placerita Canyon. It was here that gold was first discovered in California, clinging to the roots of some wild onions dug up one March afternoon by Francisco Lopez, a local rancher. The year was 1842, six years before gold was found at Sutter’s Mill.

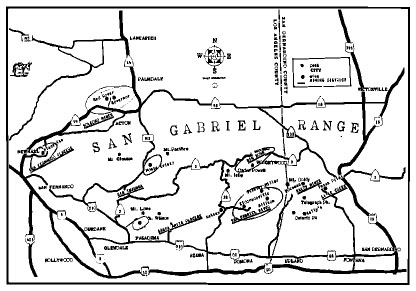

Lopez’ discovery sparked California’s first gold rush. Since then, thousands of miners have picked and panned the San Gabriel Mountains north of Los Angeles, some continuing to the present day. The years have worn away most evidence of this forgotten gold rush. But hidden high up in quiet canyons or on treacherous granite ridges, one can still find reminders of a time when hardy souls extracted a living from these mountains.

Placerita Canyon State Park, three miles east of Newhall, is where it all got started. The Oak of the Golden Dream, a twisted old California Live Oak, stands at the west-end of the park, north of the highway. Some old machinery and a small museum mark the site where early prospectors took $80,000 in gold out of this canyon (no panning is allowed anymore within the park boundaries). The small stream runs only a few months each year and was bone dry this past July, the fifth straight year of drought in the state.

Lack of water was a major obstacle for the placer miners of the 19th century. The Mexicans who did most of the mining in Placerita and nearby canyons used dry panning to winnow out the gold, but the process was not efficient. Even so, the placer gold soon gave out. By 1870 the streambeds yielded little to prospectors.

But soon they were locating the veins where the placers originated. Copper ore was discovered while surveying for a railroad to connect Los Angeles with the Mojave Desert in 1853; but at the time, it was not considered important. It was not until 1861 that miners went back after the copper – and then discovered, in the process, silver and gold.

Thus began the boom in Soledad Canyon. The town of Soledad, also known as Ravenna, quickly sprang to life. Then it died, then it revived again. By 1868, it had enough residents that a U.S. post office came to town. Through the lean years, the Mexican miners kept things going. They weren’t of the boom mentality that kept their Anglo counterparts hopping from one bonanza to the next.

The Soledad lode mines proved much more profitable than early placer operations. Mines such as the Governor, the Don, and the Red Rover boomed and busted for almost a century until they went dormant in the early 1950’s. When the Governor mine shut down in 1942, it had produced more than $1.5 million–making it the best-paying mine in Los Angeles County. Not much mining continues in the old Soledad District these days, but the sites have left a permanent mark on the hills.

Lu Anne Warren, author’s wife, standing in front of the entrance to the Monte Cristo Mine

The Legendary Monte Cristo find in Placerita Canyon was not the first discovery of gold in California, either. It was simply the first documented claim. Rumors of gold circulated as far back as the late 1700’s. One legend surrounds the Lost Padres Mine, which was supposed to have been connected with Mission San Fernando. Vast amounts of gold were said to exist at Mill Creek.

The Legendary Monte Cristo find in Placerita Canyon was not the first discovery of gold in California, either. It was simply the first documented claim. Rumors of gold circulated as far back as the late 1700’s. One legend surrounds the Lost Padres Mine, which was supposed to have been connected with Mission San Fernando. Vast amounts of gold were said to exist at Mill Creek.

The legend can’t be verified, but gold does exist high up in Big Tujunga Canyon near Mill Creek. A small gold rush hit this area in the late 1880’s, and some mining continues to this day. Some speculate that the Lost Padres Mine would later become known as the Monte Cristo, the best producer of the Big Tujunga mines.

The two-mile hike up to Monte Cristo mine from Monte Cristo Campground on Angeles Forest Highway takes you past the Black Crow mine (only the foundation of two buildings are left) and the Black Cargo–a small operation that is continuing today. About a half-mile beyond is the Monte Cristo, which has also been worked recently.

The Monte Cristo, which is not posted, looks like its tenants moved out just last week. Several abandoned houses sit in the junction of two creeks. Old machinery is strewn about, including an old rusted-out, bullet-riddled car. Little of it appears to date back to the mine’s peak years of 1923-1928. Fairly new-looking beer cans suggest the area is populated on the week-ends, if not worked occasionally.

The mine was first discovered by Mexicans and perhaps Indians before that. The first documented, full scale mining began around 1893 and was abandoned shortly thereafter. In 1895, Captain Elbridge Fuller took over the mine. Fuller seemed to have difficulty keeping partners. He either sold them out or drove them away. One of them was found dead with his head blown off. Fuller abandoned the mine after two decades.

Bur Fuller moved too soon, it seems; because the next owner turned the mine into a success. Fred Carlisle developed six tunnels and made $70,000 during 1927. But Carlisle too, saw the ore run low. The mine closed in 1942 by order of the War Production Board.

Close to Home: Probably the most accessible of the old mines, is the Dawn Mine, in Millard Canyon just above the Altadena. It’s a five-mile round trip hike, involving a lot of boulder hopping and stream crossings. A worthwhile hike even without a mine at the end, it takes you through a beautiful riparian woodland, a wonderful seclusion remarkable for its proximity to the city below.

Gold was found here in 1895 and the mine was worked into the early 1950’s. Like most of the mines of the San Gabriels, it was more ambitious than profitable. The main shaft, which ran 1,200 feet into the mountain, is still open (short assays can be found nearby on the canyon walls). Old machinery litters the canyon bottom, some of it crushed like aluminum cans between the boulders. The foundation of the miner’s cabin is located a quarter-mile below the mine. One of its owners built a trail up the canyon to connect with the Mount Lowe Railway, a marvelously-engineered railroad that ran from Altadena to Mt. Lowe in the early part of this century.

“The Dawn Mine followed the pattern of the great majority of mining ventures in the San Gabriels: initial promise, hard work, diminishing returns, and abandonment,” writes John w. Robinson, an expert on the San Gabriel Mountains.

For anyone still looking for gold in the San Gabriel Mountains, the most likely place to find it is in and around the East Fork of the San Gabriel River. The most profitable mining in the mountains was done here, and it’s still the best spot for recreational-scale mining.

Little is left of the placer operations here; but at one time, this canyon teemed with miners. The East Fork was the best-producing district of the San Gabriel Mountains. As much as $13 million in gold was recovered here. Once again, water was a major problem. But this time, it was the flood waters that periodically wiped out operations–one reason so little is left of the streambed operations.

The small town of Eldoradoville was wiped out in 1859. Eldoradoville was a tough little town of three stores and half a dozen saloons. One miner claimed he made more money by sluicing the sawdust from the floor of a local saloon, than by mining the canyon. The place was rebuilt after a flood and then prornptly destroyed again in 1862. There is a campground there now, a more conservative gamble against nature.

Hydraulic mining began in the canyon around 1871 and closed down in 1874 due to legal difficulties. Nevertheless, the energy and creativity invested into establishing hydraulic works, and the amount of gold extracted by it, was tremendous. The two major operators each extracted many thousands of dollars per month in gold by hosing down the canyon walls.

The East Fork saw a boom during the Great Depression. Eldoradoville became, “Hooverville,” a town of cardboard shacks populated by jobless men trying to make some money by gold panning. The town was washed away in a flood during 1938. Along with the town, all of the road was washed away except for a bridge that arches 250 feet above the East Fork Narrows. It’s called “The Bridge to Nowhere.”

Profitable lode mining was done on the rugged mountains above the East Fork, as well. The largest mine was the Big Horn. The spectacular mill remains in good shape. But recent exploration has begun again in the mine and the road is fenced, blocking any view of the mill.

The mine was discovered in 1895 by Charles Vincent who was hunting big-horn sheep. During its peak years of 1903-1906, $40,000 in gold was extracted–about $100,000 in all. Mining continued sporadically until the early 1940’s. Occasional exploratory work has been done since, .and the mine is currently owned by Centurion Gold Ltd.

The four mile round trip hike from Vincent Gap to the mine yields a terrific view of the East Fork watershed. Mt. Baldyand Iron Mountain fill the view to the southeast. Even the ridge that connects the peaks–some of the most rugged terrain in the San Gabriels was mined in the early part of this century .The Allison, the Baldora, the Gold Dollar, the Eagle and the Stanley-Miller are in this vicinity. Only the Allison is reasonably accessible, but even it requires one of the toughest hikes in the mountains. Not much gold was taken out of any of them the Allison extracted about $50,000 from the mountain. These high-altitude mines are monuments more of courage than business acumen.

There ~gold in the San Gabriel Mountains, but so far the hills have beaten back the prospectors. Until a new bonanza is discovered, California’s first gold rush remains only a colorful page in history.

For more information. The best resources available on historical mining in the San Gabriel Mountains are by John W. Robinson. See his books, Mines of the East Fork, Mines of the San Gabriels, and his trail guide Trails of the Angeles. Also check out Where to Find Gold in Southern California by James Klein

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy a basic gold prospecting kit.

- More on the history of gold

- More about gold

- More about how to find gold

- Schedule of upcoming events