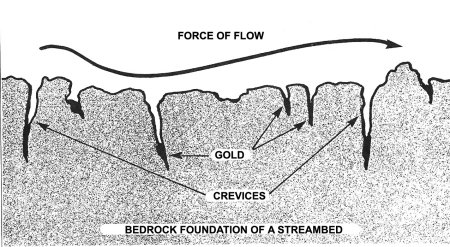

Dredging technique in gold-bearing streambeds mainly is focused upon removing the over-sized rocks (any rock which is too large to be sucked up the suction nozzle) from the work area of the dredge-hole. In most hard-packed streambeds, this removal of the over-sized material is the bulk of the dredger’s work. From a production standpoint, a large portion of this work has to do with freeing and removing the over-sized rocks from the streambed in an orderly fashion.

Hard-packed streambeds are laid down in horizontal layers during major flood storms. Generally, the streambed is put together like a puzzle, with different rocks locking other rocks into place. Usually, because of gravity, rocks higher up in the streambed (laid down later) are locking lower rocks (laid down earlier) into their position within the streambed.

Because of this, we have found the best means of production is to dredge the hole down a layer at a time. We call this a “top cut.” If you take down a broad horizontal area of the streambed all at once, you uncover a whole strata of rocks which are interconnected like a puzzle. Then, you can see which rocks must be removed first so that you can free the others more easily. This really is the key to production dredging!

Generally, there are two things that drastically slow down the production of less-experienced gold dredgers: (1) plug-ups and (2) “nitpicking.”

The time and energy spent freeing plug-ups from the hose and power-jet cuts directly into how much progress will be made in the dredge-hole.

Plug-ups are caused by rocks jamming in the dredge’s suction hose or power-jet. Everyone gets a few of these. Inexperienced dredgers get many! This comes from not understanding which types of rocks, or combination of rocks, to avoid sucking up the nozzle. Basically, this knowledge comes from hard-won experience in knocking out hundreds or thousands of plug-ups until you reach the point where you become more careful about what goes into the nozzle. I have covered this area quite thoroughly in my “Gold Dredger’s Handbook”

Plug-ups are caused by rocks jamming in the dredge’s suction hose or power-jet. Everyone gets a few of these. Inexperienced dredgers get many! This comes from not understanding which types of rocks, or combination of rocks, to avoid sucking up the nozzle. Basically, this knowledge comes from hard-won experience in knocking out hundreds or thousands of plug-ups until you reach the point where you become more careful about what goes into the nozzle. I have covered this area quite thoroughly in my “Gold Dredger’s Handbook”

During the past several years, some dredge manufacturers have started building dredges using over-sized power-jets. This means that the inside-diameter of the jet-tube is not reduced in size from the inside diameter of the suction hose, helping to greatly reduce the number of plug-ups a dredger will get while in production. Because of this, an oversized jet would be high on my personal priority list if I were in the market for a dredge!

So, the combination of some practice in learning which types of rocks to avoid sucking up the nozzle, and the over-sized power-jet on modern dredges, will eliminate most of the plug-ups that would otherwise hinder production.

The other main loss of production, which we are all guilty of to some extent, comes from a poor production technique which we call “nitpicking”. Nitpicking is when you are trying to free rocks from the streambed which are not yet ready to come out. Nitpicking is dredging around and around rocks which are locked in place by other rocks that need to be freed-up first. Nitpicking is when you are doing things out of the proper order!

When you find yourself making little progress, the key is almost always to widen your dredge-hole.

Production dredging means moving gravel through the nozzle at optimum speed. This is accomplished by making your hole wide enough to allow the over-sized rocks to be easily removed. As soon as you find the rocks are too tight to come apart easily, it is usually time to widen the hole again or take the next top cut. “Top cut” is the term we use to describe when we take a bite off the top-front section of a dredge hole to move the working face forward. “Working face” is the portion of the excavation that we are mining.

An underwater dredging helper can be a big help to remove over-sized material from the dredge-hole. Basically, there are two completely different jobs in an underwater mining operation: (1) nozzle operator (N/O) and (2) rock person (R/P). The nozzle operator is responsible for getting as much material up the nozzle as possible during the production day. Therefore, it is his or her responsibility to direct how the dredge-hole is being taken apart. The rock person has the responsibility to help the nozzle operator by removing those rocks that are immediately in the way of production.

Since there are plenty of oversized rocks that can be removed from a production dredging operation’s work area, it is important that the R/P have some judgment as to which rocks ought to be moved first. Ideally, he will pay attention to what the N/O is doing, and focus his or her efforts primarily on those rocks which are immediately in the nozzle’s way.

The rock person should be moving the very next rock that is in the nozzle’s way.

The rock person should be moving the very next rock that is in the nozzle’s way.

Silt is usually released when a rock is moved out of the streambed. So an R/P must be careful to not “cloud-out” the hole (loss of visibility). This can be avoided by concentrating on (a) moving those rocks that are near to where the N/O is working (this is the first priority), or (b) moving those rocks that have already been freed from the streambed, but not yet removed from the hole.

On occasion, an R/P unwittingly takes over the production operation by randomly moving whatever rocks he or she happens to see. This then causes the N/O to have to follow the R/P around, sucking up the silt which would otherwise cloud-out the dredge hole. This generally results in slowing down production. We have found that it is much better if the R/P accepts the position of being the N/O’s assistant, which allows the latter to direct the progress of the dredge-hole.

The nozzle-operator should communicate with his helpers where he wants to take a cut off the front of the hole.

The nozzle-operator should communicate with his helpers where he wants to take a cut off the front of the hole.

Since production is controlled by how efficiently rocks can be removed from the dredge-hole, it is important to understand that they must also be strategically discarded in a manner which, if possible, will not require them to be moved a second or third time. Generally, this means getting each rock well out of the hole–as far back as necessary. Good judgment is important on this point. You only have so much time and energy available. How far that over-sized rocks will need to be removed from the hole is somewhat dependent upon how deep the excavation is going to go. Early on, we often must guess about this. Sometimes, the streambed turns out to be deeper than we thought it would be. Then, we find ourselves turning around and throwing all the cobbles further back away from the hole. This is not unusual.

We also must use our best judgment to not waste our limited time and energy resources. We really do not want to move all those tons and tons of rocks any further than necessary to allow a safe, orderly progression in the dredge-hole.

As we move our hole forward, and as we dredge layers (“top cuts”) off the front of the hole, we try to leave a taper to prevent rocks from rolling in on top of us. This is an important safety factor. Also, since the N/O’s attention is generally focused on looking for gold, the R/P should be extra vigilant in watching out for safety concerns. Any rocks or boulders that potentially could roll in and injure a team-mate should be removed long  before they have a chance to do so.

before they have a chance to do so.

The rock-person’s attention should always be on safety. If there is danger, he or she should point it out immediately to the Nozzle-operator.

Some rocks will be too large and heavy to throw out of the hole. Therefore, it is good technique to leave a tapered path to the rear of your hole so that boulders can be rolled up and out. If you cannot remove boulders from your hole, the hole may become “bound-up” with over-sized material. This can create a nitpicking situation. It is important to plan your excavation to allow you a certain amount of (safe) working area along the bottom of your dredge hole so you can stay in balance while working.

If you see boulders being uncovered which are too large to roll out of the hole, you should immediately start making room for them on the bedrock at the back of your hole. You normally accomplish this by throwing or rolling other rocks further behind. This takes planning in advance.

Winch Operator Watching Closely For Diver Signals

Sometimes winching is necessary to remove large boulders or an abundance of large rocks from a dredge-hole. However, because winching takes additional time, the pay-streak usually must contain more gold to justify the time and effort that is required.

The amount of streambed material that you are able to process through a gold dredge will determine the volume of gold that you will recover. Actually, this volume-to-recovery ratio is true of any type of mining operation, whether it is a large-scale lode mine, a small-scale miner using a gold pan, or anything in-between.

The smaller the amount of material that a dredging program has the capacity to process, the richer the pay-dirt must be to recover the same amount of gold. Consequently, a smaller-volume operation often needs to invest more time and energy into sampling to find the more-scarce, higher-grade pay-streaks. For this reason, smaller-volume operations generally spend more time sampling, less time in production; and, therefore, usually recover less gold. But not always!

Having said that, I should also say that successful gold recovery depends upon more than the size of the dredge. A lot has to do with the skill of the operator(s).

As a general rule, gold mining on any scale is volume-sensitive. If you can dredge twice the volume of streambed material, not only can you recover twice the amount of gold, but you may find (many) more lower-grade gold deposits which can be productive when developed. You can also dredge deeper sample holes. This allows you to reach deeper pay-streaks. This is why we always advise beginning gold dredgers to go out and find an easy location where they can practice their basic gold dredge production techniques to improve their speed before they begin a serious sampling program.

It is a good idea to practice your dredging skills, so that you can operate the nozzle efficiently while moving your own oversize material out of the way.

It is a good idea to practice your dredging skills, so that you can operate the nozzle efficiently while moving your own oversize material out of the way.

An inexperienced dredge-miner will sometimes be so slow in volume-production, that he or she may miss valuable pay-streaks simply for lack of being able to process enough gravel, or lack of ability to dredge his or her sample holes large or deep enough during sampling. An inexperienced dredge operator also may not even be aware this is the problem.

When you dredge a sample hole, you must evaluate how much gold you recover against the amount of time and work it took to complete the test hole. If you are only moving at 20% of your potential production speed, you easily can make the mistake of walking away from excellent pay-streaks just because you will believe they are not paying well enough.

When we run larger-sized (8-inch or larger) gold dredges, we almost always have at least two divers working together underwater. The reason for this is because running an eight or ten-inch dredge in six feet or more of streambed material requires that an overwhelming number of over-sized rocks must be moved all the way out of the dredge-hole by hand. This varies from one location to the next. But generally, in hard-packed, natural stream-beds, somewhere between 60 and 75 percent of the material is too large to process through an eight-inch dredge. This is where second and third persons become a big help. A sole-operator in this type of material, when it is deeper than five or six feet, is going to spend a great deal of time throwing rocks out of the hole, rather than operating the suction nozzle.

The smaller the dredge, the shallower the material that a single operator will be able to manage efficiently. Also, some hard-packed streambeds require that most of the over-sized rocks be broken free with the use of a pry bar. This further decreases the amount of nozzle-time on a single-person dredging operation.

In the final analysis, it is the volume of material that is sucked up the nozzle (in any given location) that determines gold production. However, the efficiency with which the over-sized material is moved out of the way has a direct impact upon how much gravel and gold will be directed up the suction nozzle. So, gold production ultimately is controlled by how well the over-sized material (rocks too large to pass into the suction nozzle) is managed. The nozzle-operator’s focus, therefore, should be on directing the nozzle to suck up the gravel that will make it easier to free more over-sized rocks, rather than indiscriminately sucking up any gravel in the hole. In other words, the Nozzle operator should be actively pursuing a plan that keeps the Rock person busy right there where the action is happening!

If a rock person(s) is added to the operation, he or she must increase the program’s efficiency by at least as much as the percentage of gold which he/they is going to receive. This is not difficult to accomplish if conditions are right and the dredging team is organized.

On the other hand, if you are operating a dredge in two or three feet of hard-packed streambed, adding a second person may not increase your production speed enough to make it worthwhile to pay him for his time. This is because the material is shallow, and you may not have to toss the over-sized rocks very far behind in the dredge hole (less effort required to make progress).

When I am operating a production dredge in five or six feet (or more) of streambed material, I can literally bury a rock person with over-sized rocks, and make my helper work like an animal all day long. I also have to work like an animal to accomplish this. The result is a good-paying job for my helper and a substantial increase in my own gold recovery.

When I find myself working in eight or ten feet (or more) of material, I must have at least one or two (or more) rock person(s) to help me. Otherwise, I will be completely buried with cobbles and over-sized rocks all day long and will get in very little nozzle-time.

All of this also applies to smaller-dredge operations. Your ultimate success will be directly proportional to how much material you can get up the nozzle of your dredge in the right locations. The more efficiently you can make that happen, the quicker you will get your nozzle into pay-dirt.

Large-rock management is important! Since most of the material in a natural, hard-packed streambed will be too large to go through the suction nozzle, the progress and speed of your operation will directly depend upon how quickly and efficiently the oversize (cobbles and boulders) materials are moved out of the N/O’s way. Dredging is not just a matter of sucking up some gravel; at least not in the places where most pay-streaks are found.

As shown in the following important video segment, in most pay-streaks, the only gravel that gets sucked up is that which is found between the over-sized rocks. So the key to continued progress depends upon management of over-sized material:

A cutter-head consists of a rotating series of hardened-steel blades that are designed to cut into sand, clay or classified gravel. It does not have the capability to cut through hard-packed streambeds that are made up of over-sized rocks and boulders.This is the reason that cutter-head dredges do not work well in hard-packed streambeds; because they are continuously up against rocks that must be moved out of the way by divers. But it is too dangerous to put divers in a dredge excavation where a cutter-head is operating.

A cutter-head consists of a rotating series of hardened-steel blades that are designed to cut into sand, clay or classified gravel. It does not have the capability to cut through hard-packed streambeds that are made up of over-sized rocks and boulders.This is the reason that cutter-head dredges do not work well in hard-packed streambeds; because they are continuously up against rocks that must be moved out of the way by divers. But it is too dangerous to put divers in a dredge excavation where a cutter-head is operating.

So, there is a lot of good to be said about organizing a system to get the rocks moved out of your way as quickly and efficiently as possible. This is true in dredging on any scale and regardless of whether you are working alone or with a team.

The reason why larger dredges can get more accomplished in gold-bearing streambeds is usually not because they will suck up more gravel. It is because a larger hose and nozzle will suck up a bigger rock. Every rock that can go up the nozzle is a rock that does not need to be packed out of the dredge-hole by hand. This is the primary factor that speeds things up with a larger dredge.

Another major advantage of a two-person team is the substantial amount of emotional support which a second person can add to the operation—especially when you are dredging in deep material, or when you are sampling around for deposits and have not found any in awhile.

On the other hand, the wrong person can inhibit the operation, either physically or emotionally. So, you must be especially careful to select teammates who have work ethics, moral standards and emotional endurances that are similar to your own.

In my own operations, we have found that the key to good teamwork is in establishing standard operating procedures for nearly everything we do. We also work out standard underwater signals. This takes quite a bit of planning and communication in advance, and it is an ever-continuing process. We have standard procedures for removing plug-ups from the hose and jet. We have standard procedures for moving the dredges forward and backward during operation. And, we have standard procedures for every facet of the underwater work — from moving the raw material that is in front of us, to the placement of tailings and cobbles behind our dredge-hole.

As noted above, volume is the key to success—at least to the degree of success. We take this aspect of the work quite seriously in my own operations — to the point where every single moment and every single physical effort is regarded as important to the operational-moment while we are dredging. You will never find the members of my team socializing or goofing-off during the underwater production hours. We allow ourselves to relax during the off-work hours and lunch break. But during production-time, we are entirely focused on the needs of the operation. We treat the dredging-portion of the operation like a competitive team athletic sport. We are not competing against each other. In a team effort, we compete against the barriers that Mother Nature has constructed for us to overcome so that we can recover volume-amounts of gold. To us, our teamwork is kind of like running a relay race. It is rewarding this way when we really synchronize our efforts.

We try to spend a minimum of six hours doing production-dredging or sampling each day. In our operation, this is normally done in two three-hour dives. Other commercial operators prefer three or four shorter dives. I know one commercial dredger in New Zealand who prefers a straight six, seven or eight- hour dive. What an animal!

I like lunch. But, I also agree with the concept of long dives; the reason being that it takes a while to get a good momentum going underwater. Every time you take a break, you need to get that momentum going all over again. What do I mean by “momentum?” Momentum in dredging is very similar to the beat of the drum in driving music. It is the continuous flow of gravel up the nozzle, with the over-sized rocks being moved out of the way in their proper order at just the right moment so that the flow of material into the nozzle is never slowed down. It is everyone doing whatever is necessary to keep that flow happening. It is about synchronizing the right rhythm at optimum speed, and keeping the beat going!

In fact, team-dredging can be kind of like an art form. It is similar to playing music. Only, instead of notes being played on several instruments to form a harmonious melody, the team produces a stream of coordinated effort, using their bodies to move the suction nozzle and the over-sized rocks, in concert, so that all of the effort works together to achieve optimum momentum and harmony.

In his or her initial enthusiasm, an inexperienced R/P may, rather than move the next rock in the path of the N/O, instead, move the wrong rock and cloud-out the dredge-hole with silt. This causes the N/O to be slowed down (1) because of the decreased visibility, and (2) because he or she must now take the time to move the proper rock out of his own way. This is the equivalent of “playing off key,” or playing the wrong musical selection. Everybody else is playing one song, while the new guy is doing something entirely different. The bottom-line for your dredging operation: less volume through the suction nozzle, and less gold at the end of the day.

On the other hand, there is enormous personal and team-satisfaction to operating within a well-structured team-dredging system. Such a system functions best when the N/O is the conductor, and the R/P plays a supporting role, anticipating in advance and taking every possible action to contribute to the N/O’s momentum.

Four-man team on Author’s commercial operation. Notice how everyone is involved up where the action is happening at the suction nozzles.

Four-man team on Author’s commercial operation. Notice how everyone is involved up where the action is happening at the suction nozzles.

This is not just about the next rock which is in the way of the nozzle. It is also about moving the dredge forward a bit as necessary to give the N/O a little more suction hose when it is needed. It is also about the dozen or so other things that are necessary to keep the flow going without a lag.

Volume-momentum is lost every time the N/O has to put the nozzle down to take care of something. That will impact directly upon the success of the operation. Every effort should be made to keep this “down time” to a minimum.

Since volume is really the key, in my own operations, we try to treat dredging pretty-much like a team sport – competitive and physical! When I give my R/P the plug-up signal, he races to the surface to quickly clear the obstruction. He doesn’t just mosey on up there. He moves up there, like running for a touchdown or rounding the bases for the winning home run. This is also the sense of urgency with which he returns to the hole as soon as the plug-up is free. When he sees that rocks are stacking up in the hole, he doubles his pace to catch up. When caught up, he looks around to see where other cobbles might be moved out of the way, without clouding the hole. Or, he might grab the pry bar and start breaking rocks free for the nozzle operator. At the same time, when I am operating the nozzle, I am doing my own job—getting as much material through the nozzle as humanly possible while uncovering new rocks to be moved by the R/P, with the minimum number of plug-ups. And, I do not stop for anything if I can help it. If something else needs to be done, I delegate it to my R/P or other helpers so that I can keep pumping gravel up the nozzle. That’s my job! Everyone’s gold-income depends directly upon how much material is sucked up.

While this statement is also true when you work alone, every effort counts for something in production team dredging. Therefore, everyone needs to pay attention to what is going on in the dredge-hole. R/P’s particularly have to be able to switch gears quickly. At one point, there may be a pile of rocks which needs to be thrown out of the way. The next moment, even before the R/P has moved many of those rocks, he or she may notice something else that is directly impeding the N/O’s progress—like a boulder that needs to be rolled out of the way, or a particularly-difficult cobble which needs to be broken free with the pry bar. The main objective in everyone’s mind should be to support the N/O’s progress. Whatever impedes his progress should be the priority and get immediate attention.

While this statement is also true when you work alone, every effort counts for something in production team dredging. Therefore, everyone needs to pay attention to what is going on in the dredge-hole. R/P’s particularly have to be able to switch gears quickly. At one point, there may be a pile of rocks which needs to be thrown out of the way. The next moment, even before the R/P has moved many of those rocks, he or she may notice something else that is directly impeding the N/O’s progress—like a boulder that needs to be rolled out of the way, or a particularly-difficult cobble which needs to be broken free with the pry bar. The main objective in everyone’s mind should be to support the N/O’s progress. Whatever impedes his progress should be the priority and get immediate attention.

The key to a productive underwater support person is having him or her work to help keeping gravel flowing into the suction nozzle.

The only time I intentionally slow things down is when I am uncovering the gold. I have to keep an eye on that to follow the pay-streak. However, as explained in the following important two video segments, you can also slow down too much by looking. You have to find the proper balance between looking and getting volume up your nozzle:

If the pay-streak is good, I also point out the gold to my helpers as I uncover it. There is emotional gain from this. Everyone deserves the boost. The gold eventually gets spent or hidden away. The memories last your entire lifetime! As demonstrated in the following video sequence, there are few things in life that will give you a bigger emotional boost than finding one of Mother Nature’s rich golden treasures:

As the following video segment demonstrates, once you locate a high-grade pay-streak, it is also very important to invest enough time to locate the downstream and left and right outside boundaries of the deposit. This is to make sure that you are able to develop the whole deposit without burying part of it under tailings or cobbles:

When things get too confused inside the dredge-hole, sometimes the N/O must put down the nozzle and help organize in the hole (move cobbles and boulders out of the hole). But, everyone should be keenly aware of the operational situation that actual production momentum (gravel up the nozzle) has stopped and that it needs to get underway again just as soon as possible.

As noted earlier, and demonstrated in the following video sequence, we take top-cuts off the front of the dredge-hole in production dredging, and we take the material down to the bedrock in layers. We do this because it is the fastest, safest, and most organized method of production dredging:

Sometimes, when conditions are right for it, an R/P may be working right next to the nozzle, breaking the next rock free and quickly throwing it behind in the hole. However, on every top-cut, there comes a time when the N/O decides to drop back and begin a new cut to take off the next layer. The R/P has to pay close attention to this and follow the N/O’s lead. Otherwise, he or she might finish breaking free a rock up in the front of the hole when there is no-longer a nozzle there to suck up the silt. That would be an error.

In other words, the R/P has to keep one eye on what the N/O is doing all the time. Because, if the N/O is a dynamic and energetic person, he or she certainly will not be following the R/P around the dredge-hole. The N/O has to orchestrate the effort. So all of the support-players should be paying close attention and assisting in the N/O’s next move. A good nozzle operator takes apart the hole with an organized method that is easy to follow by the others.

Teamwork also extends up to the dredge-tender on the surface, if you have one. The dredge-tender should continuously monitor the water-volume flowing through the sluice box. If it visibly slows down, he should suspect a plug-up and take steps to locate and clear it. Sometimes, the water-volume has been reduced simply because the N/O has temporarily set the nozzle down over a large rock in the hole. But, on the occasions when there is a plug-up, it is a mark of great teamwork to have a tender handling the problem immediately without having to be told. Volume through the sluice box should also be continuously on the tender’s mind. When gravel stops flowing, he or she should be thinking that something might be wrong.

Teamwork also extends up to the dredge-tender on the surface, if you have one. The dredge-tender should continuously monitor the water-volume flowing through the sluice box. If it visibly slows down, he should suspect a plug-up and take steps to locate and clear it. Sometimes, the water-volume has been reduced simply because the N/O has temporarily set the nozzle down over a large rock in the hole. But, on the occasions when there is a plug-up, it is a mark of great teamwork to have a tender handling the problem immediately without having to be told. Volume through the sluice box should also be continuously on the tender’s mind. When gravel stops flowing, he or she should be thinking that something might be wrong.

When the flow slows down through the recovery system, the tender should just assume there is a plug-up that needs to be freed up from the surface.

That same level of anticipation and teamwork should also apply in other areas, as well. When the tender sees that the dredgers are moving forward in the hole, he should ensure that the dredge is being moved forward accordingly. This is so the N/O will always have a comfortable amount of suction hose to work with. As demonstrated in the following video sequence, different-sized dredges require different lengths of suction hose to allow the nozzle operator a comfortable amount of movement and flexibility:

Good teamwork involves a lot of close observation and timely anticipation to minimize the number of actual orders that need to be given and the consequent amount of down-time. Most of the activity is handled by standard operating procedures which require some planning and communication in advance.

As you might imagine, there are some different opinions about all of this. Some people are simply not running any races. This is fine; but they must understand that they do not have the same gold-recovery potential as others who are working at a faster pace—or, with a more organized system.

Generally, you will not hear anyone on my team complaining—especially when it is time to split-up the gold that we have recovered.

There is not anything difficult to understand about successful gold dredging techniques. The process is quite simple. Serious dredging on any scale is a lot of hard work. Volume is the game! The faster, deeper and more efficiently you can dredge the sample holes, the faster you will find the pay-streaks—and, the better you will make them pay. Even with smaller dredges.

At the times when you are not finding commercial amounts of gold, there is at least the satisfaction of knowing that you are accomplishing optimum performance. And, when you do locate the deposits, the sky is the limit!

Most intermediate and larger-sized gold dredges come with built-in hookah-air systems. These attach to the same engine that powers the water pump. As demonstrated in the following video segment, air for breathing underwater is generated by an air compressor, passes down through an air line, and provides air to a diver through a regulator, similar to what is used by SCUBA divers:

Most intermediate and larger-sized gold dredges come with built-in hookah-air systems. These attach to the same engine that powers the water pump. As demonstrated in the following video segment, air for breathing underwater is generated by an air compressor, passes down through an air line, and provides air to a diver through a regulator, similar to what is used by SCUBA divers: The early miners who came to California (and elsewhere) during the 1849 gold rush (and later) did find and recover many of the easy-to-find gold nuggets and rich deposits. During those early days, the deposits had to be easy to find and recover; because recovery methods and processing capabilities were very limited. Suction dredge technology allows modern-day gold and gemstone miners to prospect and mine for mineral deposits in places where earlier miners were not able to go. This is true in the deeper rivers (3-meters or more of water depth) all over the world. It is especially true in remote locations and/or within developing countries where modern technology is generally not available to village-miners.

The early miners who came to California (and elsewhere) during the 1849 gold rush (and later) did find and recover many of the easy-to-find gold nuggets and rich deposits. During those early days, the deposits had to be easy to find and recover; because recovery methods and processing capabilities were very limited. Suction dredge technology allows modern-day gold and gemstone miners to prospect and mine for mineral deposits in places where earlier miners were not able to go. This is true in the deeper rivers (3-meters or more of water depth) all over the world. It is especially true in remote locations and/or within developing countries where modern technology is generally not available to village-miners.

A cutter-head will just get bogged down (and damaged) in a normal hard-packed streambed.

A cutter-head will just get bogged down (and damaged) in a normal hard-packed streambed. If you want to do serious excavations with a suction dredge, you must leave the opening of the suction-nozzle as large in diameter as possible, while still reducing it enough to eliminate un-necessary plug-ups inside of the suction hose or power jet.

If you want to do serious excavations with a suction dredge, you must leave the opening of the suction-nozzle as large in diameter as possible, while still reducing it enough to eliminate un-necessary plug-ups inside of the suction hose or power jet.

A gold-dredger has an advantage, in that he or she is able to float equipment where he or she wants it to go, sucking up gravel (sampling) from various strategic areas. This is much easier than having to carry equipment around and set it up in each new area, as is required in conventional mining.

A gold-dredger has an advantage, in that he or she is able to float equipment where he or she wants it to go, sucking up gravel (sampling) from various strategic areas. This is much easier than having to carry equipment around and set it up in each new area, as is required in conventional mining. In fact, most of the work associated with suction dredging involves the organization and movement of cobbles and (sometimes) boulders.How well a person can organize and move the oversized material out of the way will determine how deep and fast the samples can be dredged efficiently. Consequently, this will also determine how quickly your sampling activity will lead you into high-grade pay-streaks. The following video segment further demonstrates this very important principle:

In fact, most of the work associated with suction dredging involves the organization and movement of cobbles and (sometimes) boulders.How well a person can organize and move the oversized material out of the way will determine how deep and fast the samples can be dredged efficiently. Consequently, this will also determine how quickly your sampling activity will lead you into high-grade pay-streaks. The following video segment further demonstrates this very important principle:

Over the many years, my various partners and I have experimented

Over the many years, my various partners and I have experimented

For example, because the weight-difference is so great, it is relatively easy to drop a particle of gold (19.6 times heavier than water) through a suspended medium of pre-sized quartz crystals (only 3 times heavier than water), because the difference in weight is more than 6 times. Therefore, with heavy metals, there is greater margin to introduce a larger variation of size-fraction (different sized material) into the jig, or a larger volume of pre-sized raw material, without forfeiting recovery.

For example, because the weight-difference is so great, it is relatively easy to drop a particle of gold (19.6 times heavier than water) through a suspended medium of pre-sized quartz crystals (only 3 times heavier than water), because the difference in weight is more than 6 times. Therefore, with heavy metals, there is greater margin to introduce a larger variation of size-fraction (different sized material) into the jig, or a larger volume of pre-sized raw material, without forfeiting recovery.

Water-flow through a jig is highly critical in the recovery of gemstones because they are so light.

Water-flow through a jig is highly critical in the recovery of gemstones because they are so light.

A dredge platform that you can move around, put divers and tenders on, pump raw material to; and pump classified materials from.

A dredge platform that you can move around, put divers and tenders on, pump raw material to; and pump classified materials from.

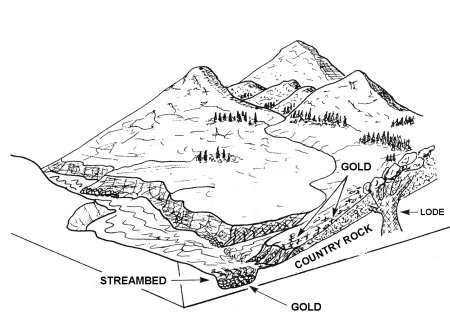

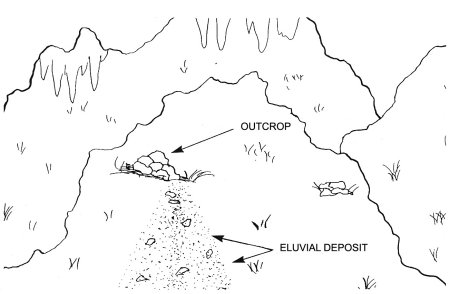

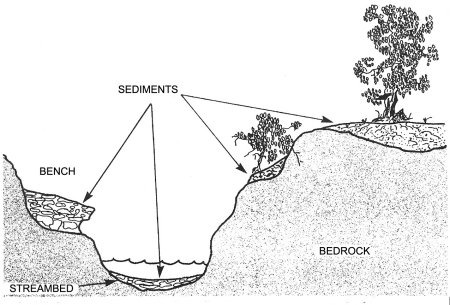

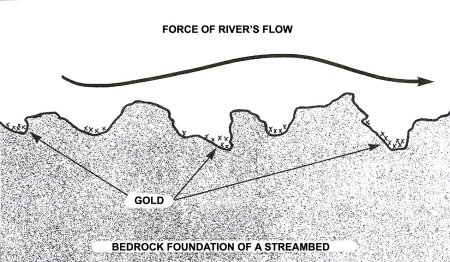

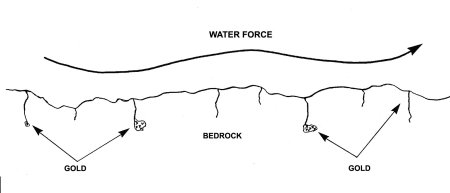

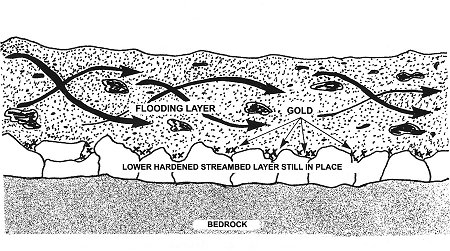

Thorndike/Barnhart’s Advanced Dictionary defines “placer” as “A deposit of sand, gravel or earth in the bed of a stream containing particles of gold or other valuable mineral.” The word “geology” in the same dictionary is defined as “The features of the earth’s crust in a place or region, rocks or rock formations of a particular area.” So in putting these two words together, we have “placer geology” as the nature and features of the formation of deposits of gold and other valuable minerals within a streambed

Thorndike/Barnhart’s Advanced Dictionary defines “placer” as “A deposit of sand, gravel or earth in the bed of a stream containing particles of gold or other valuable mineral.” The word “geology” in the same dictionary is defined as “The features of the earth’s crust in a place or region, rocks or rock formations of a particular area.” So in putting these two words together, we have “placer geology” as the nature and features of the formation of deposits of gold and other valuable minerals within a streambed

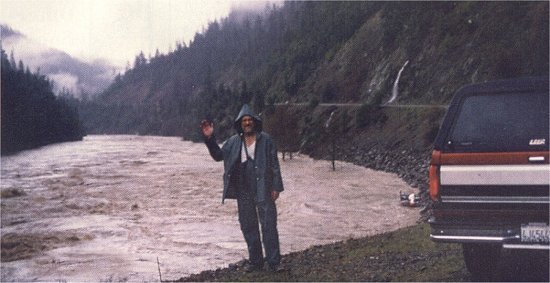

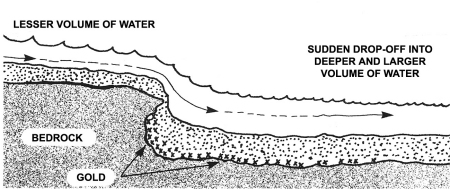

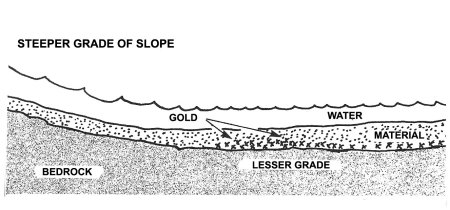

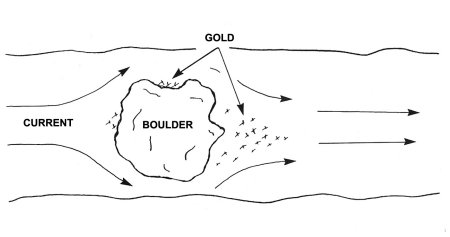

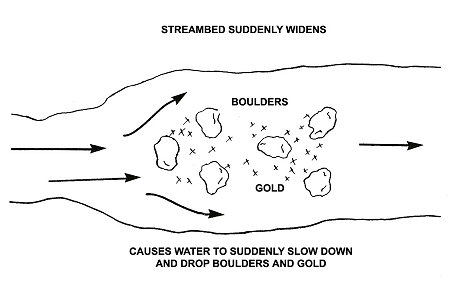

A large storm in mountainous country will cause the streams and rivers within the area to run deeper and faster than they normally do. This additional volume of water increases the amount of force and turbulence that flows over the top of the streambeds lying at the bottom of these waterways. Sometimes, in a

A large storm in mountainous country will cause the streams and rivers within the area to run deeper and faster than they normally do. This additional volume of water increases the amount of force and turbulence that flows over the top of the streambeds lying at the bottom of these waterways. Sometimes, in a

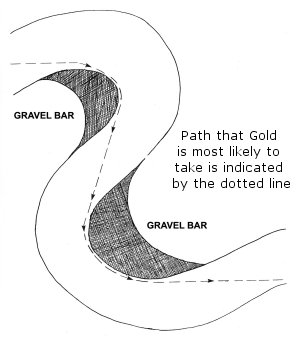

Take note that the route the gold is taking rounds each curve towards the inside of the bends in the river. While this might not be the route gold always takes in a streambed, it is true that when it comes to curves, the majority of gold deposits are found towards the inside of bends. In comparison, very few are found towards the outside. Centrifugal force causes a much greater energy of flow to the outside of the bend. This creates less force towards the inside, which allows for gold to drop there.

Take note that the route the gold is taking rounds each curve towards the inside of the bends in the river. While this might not be the route gold always takes in a streambed, it is true that when it comes to curves, the majority of gold deposits are found towards the inside of bends. In comparison, very few are found towards the outside. Centrifugal force causes a much greater energy of flow to the outside of the bend. This creates less force towards the inside, which allows for gold to drop there.

3) In what period of time?

3) In what period of time?

A well-done

A well-done  Some dredges are available with hydraulic-powered cutter-heads to help with the excavation. These are mechanical devices that help feed material evenly into the nozzle. They are most productive in doing channel-work in harbors or making navigation channels deeper or wider. Hard-packed streambeds which are made up mainly of oversized rocks and boulders will usually destroy a cutter-head device in short order.

Some dredges are available with hydraulic-powered cutter-heads to help with the excavation. These are mechanical devices that help feed material evenly into the nozzle. They are most productive in doing channel-work in harbors or making navigation channels deeper or wider. Hard-packed streambeds which are made up mainly of oversized rocks and boulders will usually destroy a cutter-head device in short order.

Plug-ups are caused by rocks jamming in the dredge’s suction hose or power-jet. Everyone gets a few of these. Inexperienced dredgers get many! This comes from not understanding which types of rocks, or combination of rocks, to avoid sucking up the nozzle. Basically, this knowledge comes from hard-won experience in knocking out hundreds or thousands of plug-ups until you reach the point where you become more careful about what goes into the nozzle. I have covered this area quite thoroughly in my

Plug-ups are caused by rocks jamming in the dredge’s suction hose or power-jet. Everyone gets a few of these. Inexperienced dredgers get many! This comes from not understanding which types of rocks, or combination of rocks, to avoid sucking up the nozzle. Basically, this knowledge comes from hard-won experience in knocking out hundreds or thousands of plug-ups until you reach the point where you become more careful about what goes into the nozzle. I have covered this area quite thoroughly in my  The rock person should be moving the very next rock that is in the nozzle’s way.

The rock person should be moving the very next rock that is in the nozzle’s way. The nozzle-operator should communicate with his helpers where he wants to take a cut off the front of the hole.

The nozzle-operator should communicate with his helpers where he wants to take a cut off the front of the hole. before they have a chance to do so.

before they have a chance to do so.

It is a good idea to practice your dredging skills, so that you can operate the nozzle efficiently while moving your own oversize material out of the way.

It is a good idea to practice your dredging skills, so that you can operate the nozzle efficiently while moving your own oversize material out of the way. A cutter-head consists of a rotating series of hardened-steel blades that are designed to cut into sand, clay or classified gravel. It does

A cutter-head consists of a rotating series of hardened-steel blades that are designed to cut into sand, clay or classified gravel. It does  Four-man team on Author’s commercial operation. Notice how everyone is involved up where the action is happening at the suction nozzles.

Four-man team on Author’s commercial operation. Notice how everyone is involved up where the action is happening at the suction nozzles. While this statement is also true when you work alone,

While this statement is also true when you work alone,

Teamwork also extends up to the dredge-tender on the surface, if you have one. The dredge-tender should continuously monitor the water-volume flowing through the sluice box. If it visibly slows down, he should suspect a plug-up and take steps to locate and clear it. Sometimes, the water-volume has been reduced simply because the N/O has temporarily set the nozzle down over a large rock in the hole. But, on the occasions when there is a plug-up, it is a mark of great teamwork to have a tender handling the problem immediately without having to be told. Volume through the sluice box should also be continuously on the tender’s mind. When gravel stops flowing, he or she should be thinking that something might be wrong.

Teamwork also extends up to the dredge-tender on the surface, if you have one. The dredge-tender should continuously monitor the water-volume flowing through the sluice box. If it visibly slows down, he should suspect a plug-up and take steps to locate and clear it. Sometimes, the water-volume has been reduced simply because the N/O has temporarily set the nozzle down over a large rock in the hole. But, on the occasions when there is a plug-up, it is a mark of great teamwork to have a tender handling the problem immediately without having to be told. Volume through the sluice box should also be continuously on the tender’s mind. When gravel stops flowing, he or she should be thinking that something might be wrong.

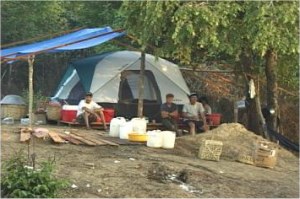

One of our first stops in Baguio was at the Department of Mining & Geology. We were looking for information and maps concerning the historical gold mining areas. Our hope was to find a sizable gold bearing river where local technology has not allowed deeper river

One of our first stops in Baguio was at the Department of Mining & Geology. We were looking for information and maps concerning the historical gold mining areas. Our hope was to find a sizable gold bearing river where local technology has not allowed deeper river

In Legaspi, our guide first took us to the beach, where local miners were recovering small amounts of gold from the beach sands using sluicing devices which were built on stilts to position them above the small waves washing up on the beach. Here follows a video segment that I captured which demonstrates the beach mining activity:

In Legaspi, our guide first took us to the beach, where local miners were recovering small amounts of gold from the beach sands using sluicing devices which were built on stilts to position them above the small waves washing up on the beach. Here follows a video segment that I captured which demonstrates the beach mining activity:

I have to say that these were perhaps the most qualified underwater prospectors I have

I have to say that these were perhaps the most qualified underwater prospectors I have  goodly amounts of gold for their effort, John and I still could

goodly amounts of gold for their effort, John and I still could