By Dave McCracken

The old-timers would construct diversions out in the active river to direct the water’s flow around where they wanted to dig.

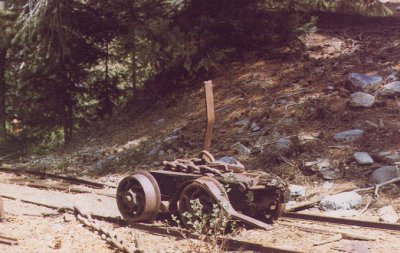

When looking at these single, stand-alone rock piles along our mining properties, it is important to understand what they are. Most of them were not formed off the backside of some massive gold recovery systems. In other words, they are not actually “tailings.” The huge single piles, as we see them on some of our mining properties, were mostly associated with large, mechanized derricks. These were used to drag buckets of material and boulders out of large hand-excavations that were being dug out in the river – or sometimes in the bars alongside the river.

The old-timers would construct diversions (called “wing dams”) out in the active river to direct the water’s flow around where they wanted to dig. Then they would roll and shovel streambed material into a large bucket or sling down in their excavations and use the derrick (often powered by a steam winch) to drag the material out of their way and into huge piles alongside their active excavations. They did this to get themselves down to the deeper pay-layers, just like we do these days. In other words, the material you see in these piles consists of the overburden and big rocks that the old-timers dragged out of their holes so that they could gain access to the richer pay-layers that were present deeper in the streambed.

Most often, the material you see in these big piles on the banks was never processed for gold-content. This explains why some of our members are already starting to recover gold out of the huge piles on one of our new claims. It also explains why some of our members have been doing so well processing the huge piles along other sections of the Klamath River.

Most often, the material you see in these big piles on the banks was never processed for gold-content. This explains why some of our members are already starting to recover gold out of the huge piles on one of our new claims. It also explains why some of our members have been doing so well processing the huge piles along other sections of the Klamath River.

Here are a few important things to understand about the huge piles:

1) Wherever you see them, you know the old-timers were working very rich ground. Because, even though a mechanized derrick was used to drag the material into a pile, it was all hand-work that placed the material into the buckets in the first place. Take a look at the size of those piles! They represent an enormous amount of organized physical effort! That labor had to be paid for. Mining companies paid for labor to perform that much work only because they were getting a return on their investment!

2) When you see more than a single huge rock pile in proximity, you know that the labor was paying off. Miners do not make repeated blunders in proximity. This new claim at K-2A has lots of huge piles. The whole Gottville mining district has them!

3) Since the rock piles did not wash away in the major flood events which occurred since they were made, we can look at the piles to get a good idea where the old-timers mined the claim. Looking at the piles, it looks to me like most of the property has yet to be mined. There will be serious, original (virgin) gold deposits present there. This is the reason we have been quietly, patiently waiting for our opportunity to buy the property.

- Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 1

- The Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 2

- Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 3

4) We must keep in mind that there was zero flood control (dams) on the Klamath River at the time when these rock piles were created. This means that all of the work to create the diversions (wing dams) and dig the excavations had to occur likely between the months of July through October. The first big rain in the fall would have put an end to the entire investment for that particular season. Following winter storm events will have completely buried the excavations. This means there was a short life span on each excavation where you see the rock piles.

5) It is likely, in many cases, that more time and effort was invested into getting an excavation down to the pay-dirt, than the time and effort invested into working the rich material.

6) No question, whatever was remaining of exposed pay-dirt had to be abandoned once the first flood event of the rainy season arrived. While it is likely that some mining companies returned to the same places during the following year, I’m certain that many did not. The fact that you don’t see continuous piles up along the whole river is evidence that much of the area remains un-mined. Good thing the old-timers did not have access to modern suction dredges or the whole claim would have been mined out!

7) Since a mechanized derrick could drag material from a long distance away, the height of the pile is not a read on how deep the streambed material is in the river. But you can look at the size of the piles to get a reasonable idea how big the excavation was in the river or on the bar.

8) To some degree, you can expect that a lot of the material you will find at the top of these rock piles will be from the places closest to the pay-layers which the old-timers were working. Add 60+ years of natural weathering (heavy rains), and you can find some nice gold concentrations in some of these piles. Otto Gaither showed me quite a stash of gold that he and some of his friends were mining out of one of their secret rock piles on the river several years ago. The gold was so good that I actually went to look at the pile. They were getting their gold right out of the top!

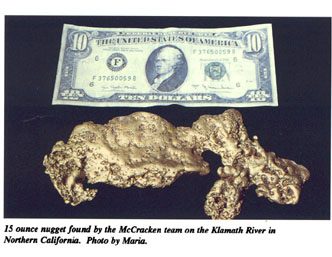

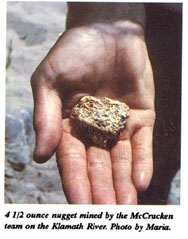

9) A wing dam was usually constructed on top of original (virgin) streambed and positioned to keep the water flowing on one side so they could excavate the material on the other side. I have seen or heard of it many times that all you have to do is mine under, and to the other side, of a wing dam to get at the very material which the old-timers were mining. My personal best day on the Klamath River (24 ounces of beautiful nuggets) was where Eric Bosch and I went just to the other side of a wing dam out in the river. We would have found a lot more gold that day, but we were too excited to work! That’s a true story! The wing dam was placed right adjacent to a huge rock pile like the ones on this new claim; a rock pile which was producing really well for several guys using high-bankers to recover gold out of the piles…

10) By now, everybody ought to know what hard-packed streambed is. This is compacted gravel and rocks which is laid down in layers during major flood events. Nearly all the high-grade gold we are going to find in the river or on the bars is going to be associated with hard-pack. I cannot overstress the importance that you need to know what hard-pack is. If you don’t, I strongly urge you to read my books and/or attend our scheduled weekend mining projects. There is a learning curve to prospecting for high-grade gold. The sooner you get through it, the sooner you will be pleased with your results. We are here to help. But it is up to you to make use of the services which we provide to help all members.

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy Gold Prospecting Equipment & Supplies.

- More about how to prospect for gold

- Schedule of upcoming events

- Books and Videos by Dave McCracken

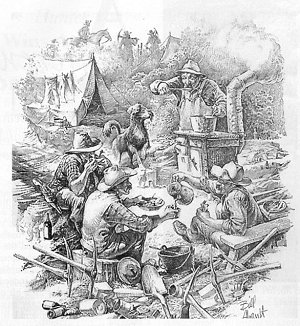

As I finished the last of the dinner dishes under my tarp “roof,” I looked out over our mining camp, nestled in the bottom of a steep, narrow, forested canyon. Camped in tents along the bank of our sparkling clear creek, we seemed very small in the miles of wilderness that surrounded us. We were three families, eleven people in all, with children ranging from five years to 21, and this was our first summer together as partners in a mining claim. Wet suits were drying on the clothesline, and the final

As I finished the last of the dinner dishes under my tarp “roof,” I looked out over our mining camp, nestled in the bottom of a steep, narrow, forested canyon. Camped in tents along the bank of our sparkling clear creek, we seemed very small in the miles of wilderness that surrounded us. We were three families, eleven people in all, with children ranging from five years to 21, and this was our first summer together as partners in a mining claim. Wet suits were drying on the clothesline, and the final  We continuously dredged-up reminders of former miners-square nails and mule shoes, hand-forged picks and other tools, and even old coins. Dimes from 1839, 1848 and 1849 and a “large” cent from 1832, all caused as much excitement as the

We continuously dredged-up reminders of former miners-square nails and mule shoes, hand-forged picks and other tools, and even old coins. Dimes from 1839, 1848 and 1849 and a “large” cent from 1832, all caused as much excitement as the  Our day finally arrived, and we were all up early, packing lunches and donning packs while the air was still crisp and dew sparkled around us on the plants. The sun was just rising over the mountain as we forded our creek and started up the mountain on the other side. It was a steep climb, and we paused often to admire the beautiful patches of wildflowers and pick raspberries.

Our day finally arrived, and we were all up early, packing lunches and donning packs while the air was still crisp and dew sparkled around us on the plants. The sun was just rising over the mountain as we forded our creek and started up the mountain on the other side. It was a steep climb, and we paused often to admire the beautiful patches of wildflowers and pick raspberries. As we looked around, sunlight streamed through large cracks between the wall-boards. How cold it must have been when the winter winds and snow came whistling through!

As we looked around, sunlight streamed through large cracks between the wall-boards. How cold it must have been when the winter winds and snow came whistling through! All too soon, it grew late and we had to cross back over the mountain and return home. We vowed we would return, but we only had two weeks left on the claim and we did not make it back. However, we planned to make the journey again the next summer.

All too soon, it grew late and we had to cross back over the mountain and return home. We vowed we would return, but we only had two weeks left on the claim and we did not make it back. However, we planned to make the journey again the next summer.

“Sourdough” was a miner who came south from Canada seeking to make his fortune in America. Most of the “Sourdoughs” returned home with empty pockets.

“Sourdough” was a miner who came south from Canada seeking to make his fortune in America. Most of the “Sourdoughs” returned home with empty pockets.

Can you imagine finding a slab of

Can you imagine finding a slab of  Have all the big nuggets and slabs of gold been found? I don’t think so. Several very interesting discoveries have been made in recent years. A California deer hunter tripped over a rock. When he picked the rock up, he found he was holding a fist-sized gold nugget.

Have all the big nuggets and slabs of gold been found? I don’t think so. Several very interesting discoveries have been made in recent years. A California deer hunter tripped over a rock. When he picked the rock up, he found he was holding a fist-sized gold nugget. One group of early miners, approximately eighteen men, traveled the millennia-old foot-trails of the Karuk people, up to a place of broad gravel bars and exposed bedrock two miles upstream from Clear Creek. For thousands of years the Karuk Indians lived along the river on similar “flat” campgrounds, ancient gold-bearing deposits of river gravel!

One group of early miners, approximately eighteen men, traveled the millennia-old foot-trails of the Karuk people, up to a place of broad gravel bars and exposed bedrock two miles upstream from Clear Creek. For thousands of years the Karuk Indians lived along the river on similar “flat” campgrounds, ancient gold-bearing deposits of river gravel!

Umm, I don’t quite know how to write this any other way than to report that the answer is no. That is, he may have looked at many of the sources, found some of them to be sure, and then wandered back to what he knew of as civilization. . . and then couldn’t find the place again. Or, he caught a fever and died or got shot in an argument over politics and couldn’t recover from the subsequent wounds. There are many instances where the discovery was made and the “natives” interrupted the process of removal and enforced strict “immigration regulations” by force of arms and left no survivors.

Umm, I don’t quite know how to write this any other way than to report that the answer is no. That is, he may have looked at many of the sources, found some of them to be sure, and then wandered back to what he knew of as civilization. . . and then couldn’t find the place again. Or, he caught a fever and died or got shot in an argument over politics and couldn’t recover from the subsequent wounds. There are many instances where the discovery was made and the “natives” interrupted the process of removal and enforced strict “immigration regulations” by force of arms and left no survivors. There is hardly a spot on earth larger than a ten dollar bill that does not have tales of lost mines and buried treasure connected with it. And one could spend three or four lifetimes just investigating the ones in his own neighborhood, unless he sharpened his investigative wits and began looking for hard evidence alone.

There is hardly a spot on earth larger than a ten dollar bill that does not have tales of lost mines and buried treasure connected with it. And one could spend three or four lifetimes just investigating the ones in his own neighborhood, unless he sharpened his investigative wits and began looking for hard evidence alone.