BY NANCY CRAGO

It is common knowledge that if one is both wealthy and strange, he or she is called eccentric. Most miners I have run across are not wealthy, but the word eccentric suits them very well.

It is common knowledge that if one is both wealthy and strange, he or she is called eccentric. Most miners I have run across are not wealthy, but the word eccentric suits them very well.

There is a miner living in the Klamath National Forest who has four gnomes near his home. They are comfortably arranged in the fallen leaves under a majestic madrone tree. When it rains, it is difficult to distinguish the brightly colored ceramic gnomes from the brilliant orange bark of the tree. There is a legend that gnomes protect gold; and in this case, the array of possessions outside, too. Last winter, their bright red hats peeked out of the snow. Very close to them, next to the manzanita bush, was a life-size miner snowman kneeling with his gold pan and pick. What else would one expect at a miner’s home near Happy Camp?

This is only one example of the magical things I have seen since learning to view the world through miners’ eyes. The miners seem to blend right into the woods and rivers and are accepted by the creatures who live there. Could it be that the “eccentric” miners are better understood by the creatures of the woods than by their fellow “civilized” men?

Last summer, while dredging on the Klamath River, I met miner-Bob (miners rarely have last names). Bob was a great hulk of a man. He would always chat a bit when passing by on the trail on his way down river. When asked when he would be coming back after work, he would say, “That depends on when the black bears want their dinner — nothing should keep a man or bear from his food.”

It seems this man would work until dusk when he saw the black bears coming from across the river to eat their evening meal. Because the forest was so dense on the opposite side, few berries and apple trees grew there. But on our side, the wild blackberry bushes were everywhere with berries as big as your thumb. It was touching to think this man, wearing a custom-made wet suit, size XXXLarge, would respect a bear’s dinner-time.

One evening in the same area, the bears came across the river and tore up the campsite of another miner while looking for their dinner. They ate all the fresh fruit, eggs and meat (except for the bologna) and other packaged sandwich meat. They also left the white bread. Perhaps we can learn something from these bears!

One evening in the same area, the bears came across the river and tore up the campsite of another miner while looking for their dinner. They ate all the fresh fruit, eggs and meat (except for the bologna) and other packaged sandwich meat. They also left the white bread. Perhaps we can learn something from these bears!

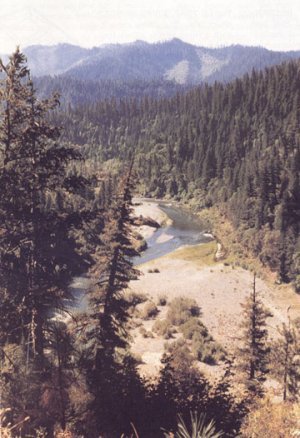

As one drives west along the beautiful, wild and scenic Klamath River road, Highway 96, one eventually comes to the Dillon Creek area. Near this area is an old highway no longer maintained. This road, with weeds growing in the middle of it, wraps around the mountains. It ends abruptly at a bridge abutment left useless by the 1964 flood.

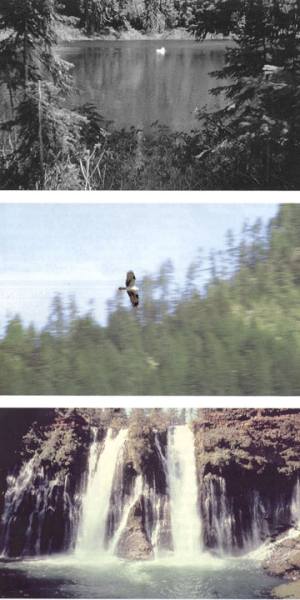

The area is much loved by the osprey, who build their nests on the broken off tops of dead trees, called snags. An old grizzled miner friend of mine went up that road on Sunday. He said, “It’s better than going to church for me, I can talk to God and his creatures up there.”

He told me as he was walking along the road in an unhurried fashion, an osprey suddenly flew from his nest and began calling to him. As the miner looked up, he thought, “What a magnificent creature you are and what beautiful feathers you have.” He was trying to imagine the view the bird would have 300 feet above the river. The miner’s view was almost overwhelming in its beauty, and he was only 100 feet or so above the river. With that, the bird continued to call the miner, flapped its wings with great force and seemed to stop in midair. From the bird, a perfect feather fell landing near where the miner stood. The feather is carefully and lovingly displayed in the miner’s home as a memento. He says it is a gift from “one of God’s creatures.”

He told me as he was walking along the road in an unhurried fashion, an osprey suddenly flew from his nest and began calling to him. As the miner looked up, he thought, “What a magnificent creature you are and what beautiful feathers you have.” He was trying to imagine the view the bird would have 300 feet above the river. The miner’s view was almost overwhelming in its beauty, and he was only 100 feet or so above the river. With that, the bird continued to call the miner, flapped its wings with great force and seemed to stop in midair. From the bird, a perfect feather fell landing near where the miner stood. The feather is carefully and lovingly displayed in the miner’s home as a memento. He says it is a gift from “one of God’s creatures.”

A novice lady-miner friend of mine wanted a nugget for her husband’s birthday present. He had never dredged one up. Not having a great deal of extra money available, she decided the best way to get one was for her husband to dredge it up. When she and her husband set out that day toward their dredge on the river, she commented she just knew he would find something special that day. As the lady stood in the river tending the dredge, a Monarch butterfly flew near her head and landed on her wide brimmed straw hat. It made no attempt to flyaway.

She remembered a local Karuk Indian saying that butterflies are the communicators for the animals, and they will bring good luck. A short while later, she walked around the triple sluice box of the dredge and there in the second riffle from the bottom in the center box lay an exquisite 22-grain nugget. She thought immediately about what a third generation old miner, Allan Copp, said in his book, “The native nugget you find in a river is unique; it is one of its kind in all of creation, and no other human hand has ever touched it…don’t sell it.”

If you want to know where someone has “punched a hole” in the river, just follow the schools of happy little fish. They fill the Klamath River, especially during the summer months. As the dredgers displace rocks in different areas along the river-bottom, word quickly spreads in the fish community. No sooner has a rock been shifted than the little fish are there to gobble up the algae and other food growing on the rocks.

Another creature who loves the dredges is the lamprey eel. They hang out in a dredger’s hole during the evening. Because of the lack of current in the hole, this is an ideal spot for them to rest. Most dredgers, when they go to work in the morning, are surprised to see the long slender snake-like body in their “office”, as one miner refers to his hole.

Steelhead and salmon prefer spending time in dredge holes because the water is much cooler and deeper, and they can rest for a while before continuing their swim upriver to their spawning grounds where they were born. Cobbles and boulders piled up in the rear of a dredge hole create hiding spots where trout and salmon can rest in comfort from predators. These holes are quickly filled in by the first fall storm, and the tailing piles are leveled out. The soft pack remaining is a nice home for the Crayfish.

If one were to ask a miner about an Entosphenus tridentatus or an Ocorhynhus Kisutch or a Salmo Gairdneri, he would probably not be able to tell you these are a Pacific Lamprey, a Silver Salmon or a Steelhead Rainbow Trout in that order. Nevertheless, there is a working arrangement between the miner and the creatures of the river.

If one were to ask a miner about an Entosphenus tridentatus or an Ocorhynhus Kisutch or a Salmo Gairdneri, he would probably not be able to tell you these are a Pacific Lamprey, a Silver Salmon or a Steelhead Rainbow Trout in that order. Nevertheless, there is a working arrangement between the miner and the creatures of the river.

Perhaps the least welcomed by lady miners are the water snakes. They, too, tend to gather near the miners working near the bank, looking for food. I noticed the numbers grew during the summer months — again the word was out — food! Miners are not the type of people who make a big deal out of what they do — except when they find a good pay-streak. If they notice something that needs to be attended to, they do so — usually quietly.

A miner I met last year noticed the highway was littered with pop cans and trash. He mentioned this to a few buddies, and one bright sunny day 40 miners quietly picked up 20 miles of trash, loaded it into their pickup trucks, and took it to the dump. They were not paid by anyone. They did it because they wanted to and “it needed to be done,” said the miner who arranged it.

A mining couple who are friends with friendly smiles and shiny eyes volunteered a story to me. They returned to their campsite one cold evening a little discouraged from their day of sluice-mining. There on the top of their tent sat a fluffy owl peering through the darkness. They considered this a gift and positive omen of abundance. It was!

There are thousands of miners who flock to the river and creeks to enjoy, not destroy. They come to see their trees and to breathe the fresh air and to sleep under the stars. They come to see the wild mallards and the black-tail deer and the otter play. They come to share a mining experience with people they never met, and end up being partners before the season is over.

As one small-scale miner said, “I never knew how proud I was to be an American until I saw an American bald eagle fly up the river at dusk. I stood there and cried at its great strength and beauty and realized these freedoms are slowly being taken away from the miner and the American people.”