It takes an incredible force of water to move boulders in a river. Once they are moving in a flood storm, they can deposit in low-velocity areas, just like gold does. But, since boulders do not have a higher specific gravity, mass for mass, than most of the other streambed materials, they can be washed downstream just about anywhere in the river during a major storm. So you should not only use the presence of boulders to guide you in sampling. You would be much better advised to focus your attention on the boulders that have been deposited along the common path of gold’s travel.

It takes an incredible force of water to move boulders in a river. Once they are moving in a flood storm, they can deposit in low-velocity areas, just like gold does. But, since boulders do not have a higher specific gravity, mass for mass, than most of the other streambed materials, they can be washed downstream just about anywhere in the river during a major storm. So you should not only use the presence of boulders to guide you in sampling. You would be much better advised to focus your attention on the boulders that have been deposited along the common path of gold’s travel.

In shallow streambed material, you can sometimes detect where important bedrock changes are located by noting where the boulders have deposited within the waterway. For a boulder, or a group of boulders, to be found in a specific location along the river’s path, there may be a sudden bedrock drop-off, a large crevice, or some other kind of lower-velocity condition in that area which caused the boulder(s) to be deposited there. Everything in the waterway happens for a reason, even if you cannot always see what it is!

If the boulder(s) is located somewhere along the common gold path, that would be a prime spot to do some sampling. In this situation, I suggest that you do not limit your sampling to the area just behind (downstream) of the boulder, though. Go around to the upstream side of it, as well. Look for any bedrock change which may have caused the boulder to stop there. If gold has moved through that area, that same bedrock change could also have caused gold to concentrate there. Finding the bedrock change that stopped the boulder, and following the bedrock change across the waterway, is a great way to locate the common gold path.

You do not always find boulders with every rich pay-streak deposit. But, it is not uncommon to find many boulders keeping company with a good pay-streak. When you do find them, most of them will probably have to be moved out of your way as you work forward through the deposit.

MOVING BOULDERS BY HAND

There can be a lot of gold deposited under and around the boulders located within a pay-streak. To get most of the gold out from under a boulder and into your suction nozzle, usually the boulder has to be moved at least a little bit.

One of the most useful tools that can help a dredger move boulders is a 5-foot (or longer) steel pry bar. If a boulder is too large to be moved to the rear of the dredge hole by hand, it can sometimes be rotated around to one side so that you can dredge out from under part of it. Then, it can be rotated around the other way to access the remaining gold and material beneath. A long pry bar can be a big help to you in moving boulders around in this way.

One of the most useful tools that can help a dredger move boulders is a 5-foot (or longer) steel pry bar. If a boulder is too large to be moved to the rear of the dredge hole by hand, it can sometimes be rotated around to one side so that you can dredge out from under part of it. Then, it can be rotated around the other way to access the remaining gold and material beneath. A long pry bar can be a big help to you in moving boulders around in this way.

The key concern while working around boulders is safety! Loose boulders in and around a dredge hole are the gold dredger’s greatest danger, especially when working alone. Boulders resting up in the streambed material are usually more dangerous than those resting on the bedrock. But, those on the bedrock can cause trouble, too, if they are loose and able to roll – particularly, if the bedrock has any slant to it.

As they are uncovered in a dredge hole, loose boulders should be moved and safely secured as a top priority. They should be placed at the rear of the hole, if possible. But, wherever they are placed, they should be positioned so they no longer pose any threat of rolling into the hole and on top of someone working there. You can place smaller rocks and cobbles under the boulders as necessary, to make certain they will not roll or slide.

If you start to uncover a boulder that is resting up in the streambed material, do not forget about it. Until it has been moved and secured safely, a loose boulder should be foremost in your mind. If it is not yet ready to be moved, and you still need to dredge around it to free it up some more, it can be useful to place an arm or a shoulder against the boulder. This way, you can feel if it starts to loosen up in the material. Do not place your arm, head, or shoulder near the underside of the boulder, however. Because, sometimes a boulder will loosen up and crash down very quickly, without much warning. Physical contact with the boulder is helpful when you cannot keep your eyes on it at every moment. The face mask limits your visual perception underwater – especially when you need to watch what is going up the suction nozzle.

The main concern here is to take all necessary precautions to keep yourself from becoming pinned or crushed beneath a boulder in your dredge hole. If a boulder pins any part of your body to the bottom, it may be difficult or impossible for you to get the necessary leverage to move the boulder enough to get out from under it. And, if you are working by yourself …? I know of two dredgers who ended their careers in just this way.

Also beware of fractured bedrock walls that tower over you. They can fall apart and drop in your dredge hole as you remove the streambed material that holds them in place. I got pinned once by a slab of bedrock that broke free of a wall as I dredged away the material that was holding it there. Luckily for me, it landed on my steel-tipped boot, and that I was dredging with another guy on that day!

Also beware of fractured bedrock walls that tower over you. They can fall apart and drop in your dredge hole as you remove the streambed material that holds them in place. I got pinned once by a slab of bedrock that broke free of a wall as I dredged away the material that was holding it there. Luckily for me, it landed on my steel-tipped boot, and that I was dredging with another guy on that day!

The second greatest danger to a dredger usually comes from a cobble falling off the side of the dredge hole and hitting the dredger in some way — like on top of the head. This can finish off a dredger just as surely as a boulder. Or, it may cause some serious pain/injury. Fingers and other body parts can get smashed if you are not careful!

Most trouble with cobbles and boulders can be prevented simply by taking your hole apart with safety in mind. The proper method of taking a dredge hole apart has already been fully covered in my Gold Dredger’s Handbook, so I will not repeat it again here. But, as a point of emphasis, the fastest way to take apart a streambed also happens to be the safest way.

Production dredging goes very smoothly and quickly when you have some area of exposed (dredged) bedrock between the non-dredged material in front of you and the cobbles, boulders and tailings behind you. When you start uncovering a boulder in the material, you should immediately begin planning where you are going to move it, once it is ready.

If you run across an occasional boulder that you cannot move by hand, sometimes you can dredge the material (and gold) out from around and under it without having to move it out of the dredge hole. You accomplish this by moving other, smaller rocks out of the hole to make room for the boulder. In this way, if there are not too many boulders, you can keep moving forward on the pay-streak without the few boulders slowing you down very much.

But, if there are a lot of large boulders down along the bedrock, you will likely discover that at least some of them will need to be completely removed from your excavation if you expect to uncover very much bedrock with your suction nozzle. Some boulders will need to be removed to make room for other boulders as you move forward on the pay-streak. If you cannot remove the boulders from your dredge hole by hand, then you will need some mechanical assistance.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF WINCHES

COME-ALONG: A “come-along” is a portable, hand-operated winching device that can be of considerable help to a small-sized digging program. It can be used to move those boulders that are not huge, but which are too large to be moved by hand. Come-alongs range in size. I recommend a larger version of the better quality, rather than the really cheap, imported models. Come-alongs have a great accessibility factor, because you can carry one just about anywhere. Their operation is somewhat slow. But, they will give you that extra edge when you need to move just a few boulders, and you do not own or want to set up a power winch.

GRIP-PULLER: Several companies make a hand-winching device that rides along on a steel cable. There is a handle that you crank back and forth, similar to a come-along. Each time the handle is cranked in each direction, the device moves an inch or two along the cable. These units also come in different sizes. In my opinion, grip-pullers are a substantial step up from a come-along, both in pulling-power and dependability. I have used these units underwater, but find that the water resistance adds substantial work to the cranking action. Still, when you are working alone, having this device in the hole with you allows you to see what the boulder is doing while you are winching it

Where you can buy winching supplies

USING YOUR TRUCK AS A WINCH: If your vehicle can be driven to a nearby position, you can stretch a cable from the vehicle to the boulder. The proper direction of pull can be rigged up by running the cable through snatch blocks (heavy-duty pulleys) which can be anchored to trees, boulders or whatever is available. Then you can use the pulling-power of your truck to help move the boulders out of the way. Four-wheel drive vehicles work better for this, especially when they are carrying a load to increase tire traction. Suggestion: It is better to connect the cable to something on the vehicle’s frame, rather than just the bumper!

When conditions are right for it, using a vehicle to pull smaller boulders can be much faster than using a come-along. One person operates the vehicle, while a diver is in the water, slinging the boulders. Safety becomes a greater concern when more than one person is involved in the pulling and the slinging of rocks. Communication and coordination between the “puller” and the “slinger” are very important to prevent serious accidents. Suggestion: If you turn the truck around and pull in reverse, you can better-see signals from your partner, and sometimes you get better traction, especially on a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Another suggestion: It is better to keep your vehicle a respectable distance from any drop-offs (like into the waterway), just in case the boulder gets momentum in the wrong direction. I know of guy who got pulled over the side of an embankment by a boulder gone wild!

When conditions are right for it, using a vehicle to pull smaller boulders can be much faster than using a come-along. One person operates the vehicle, while a diver is in the water, slinging the boulders. Safety becomes a greater concern when more than one person is involved in the pulling and the slinging of rocks. Communication and coordination between the “puller” and the “slinger” are very important to prevent serious accidents. Suggestion: If you turn the truck around and pull in reverse, you can better-see signals from your partner, and sometimes you get better traction, especially on a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Another suggestion: It is better to keep your vehicle a respectable distance from any drop-offs (like into the waterway), just in case the boulder gets momentum in the wrong direction. I know of guy who got pulled over the side of an embankment by a boulder gone wild!

Larger-sized trucks, tractors, bulldozers, and other heavy equipment can sometimes be used to move bigger rocks with even better results.

AUXILIARY TRUCK WINCHES: Auxiliary automotive winches are also able to move small to mid-sized boulders for a dredging operation with excellent results. Some of those little winching units have a wondrous amount of power. A typical 8,000 or 10,000-pound electric winch will move a surprisingly-large boulder!

If you are going to be using an electric winch, you may want to consider installing dual batteries in your vehicle. It also helps to keep the engine running while you are winching, so the batteries can quickly regain their charge between pulls.

When using a truck-mounted auxiliary winch to pull boulders, it is a good idea to block all four wheels. This precaution helps to keep the vehicle from moving, rather than the rock you are trying to pull. The front tires should be blocked especially well. If there is an embankment to worry about, it is also a good idea to run a safety chain or cable from the vehicle to some additional anchor behind, like a tree or another truck. This will protect against losing your vehicle over the embankment if the boulder happens to roll the wrong way. Sometimes this added measure is necessary just to keep the vehicle from sliding during the pull.

Probably the best kind of auxiliary vehicle winch for dredging purposes is one that can be attached mechanically to the “power take-off unit” on your vehicle’s transfer case, if it has one. With this kind of winch, you can use the full power of your truck’s engine to pull rocks. Not only will this provide you with more pulling power, but you will not have to worry about your batteries running down.

There is also a lot of good to be said for the portable electric and hydraulic winches on today’s market. I know of many smaller-scale and commercial dredgers who use them. They are quite powerful! Portable electric winches can be framed up to (1) attach to a vehicle, (2) be taken out to the dredging site, or (3) even be floated on a platform, where there is deeper water. All that is needed is an automotive battery and a means of keeping it charged up. The portable hydraulic winches can be similarly effective. The winch controls can be extended out on a longer cable and even modified to work underwater, which can be very helpful!

LOG SKIDDERS: Most gold-dredging country is also logging country. So there are quite a few log skidders around that can be leased or hired to pull boulders for you. Log skidders are usually equipped with powerful winches. They can really do a job in pulling the larger boulders! Also, you can drive them into some pretty difficult areas. Hopefully, you can work out a deal that will be ideally suited to your operation; a deal perhaps, where you pay by the hour and have the skidder arrive at a certain time each day, or whenever you are in need of it’s services.

PORTABLE POWER WINCHES: Gasoline-powered, mechanical and hydraulic winches are available in all sizes. Generally, the larger they are, the more winching-power that they produce. But, the added size and weight also makes them more difficult to pack into some of the less accessible areas.

If you find a widespread, rich pay-streak with plenty of large boulders that need to be moved, you should set up on your dredging site the most powerful winch that you are able to haul in there. The more pulling-power you have available, the smoother and faster winching will go.

I never recommend that a dredger buy a portable power winch just because he or she will be dredging. It is probably better to wait until you know exactly what your needs are. I have worked many pay-streaks where no winching was needed at all. And, in many of the pay-streaks that did require winching, a number of the boulders were so large that the small, portable store-bought type of winch would not have been adequate for the job.

You can find some pretty heavy-duty used winches for sale at about the same cost as a lighter-weight, new portable unit. I advise waiting to see what you will need before putting your money into a winch.

Having said that, here is something to consider: Mechanical winches seldom have a control mechanism which can allow the operator to stand away from the machine where all the wrestling is going on (and in the line of fire if a cable breaks). While I have used some wonderful mechanical winches, there was never a time that we were pulling a big rock that I was not worried about something going wrong with all those tons of energy happening right next to me. There is a lot to be said about electric or hydraulic units that will allow you to step away from the danger with the controls in your hand.

WINCHING COBBLES IN DEEP MATERIAL OR SHALLOW WATER

As I have stressed in other articles about dredging, the main limiting factor to progress is in how quickly oversized material (rocks that are too large to be sucked up the nozzle) can be moved out of the ongoing excavation. In deeper streambed material, there can be so many cobbles that there is no longer any room directly behind the dredge hole to throw them. You can run into a similar problem in shallow water, where the cobbles must be lifted out of the water (where they become a lot heavier) to get them behind the dredge hole. In these types of situations, it is common to fill cargo nets with your cobbles and winch them out of your dredge hole in bulk. The following video sequence was taken in an operation where we were removing big lots of cobbles from a deep excavation in just this way:

SETTING UP A HOLE FOR WINCHING

Before you start winching boulders, it is a good idea to first make sure that you have located the lower (downstream) end of the pay-streak. You do not want to winch boulders onto any part of the pay-streak that you will be working at a later time. While the winter storms could possibly move some of the cobbles and dredge tailings which were placed on a pay-streak in error, it takes much more than a winter storm to move boulders from where you winch them. Believe me; it is much better to plan ahead, so you only need to move boulders one time!

BUILDING A RAMP

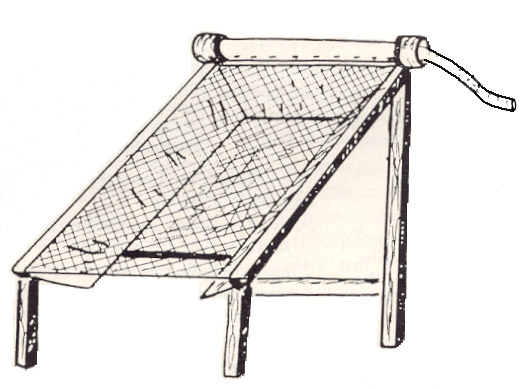

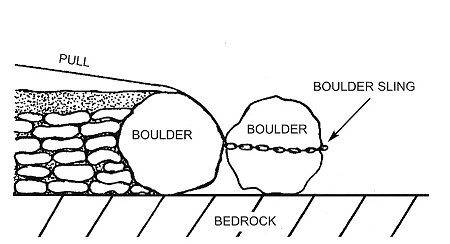

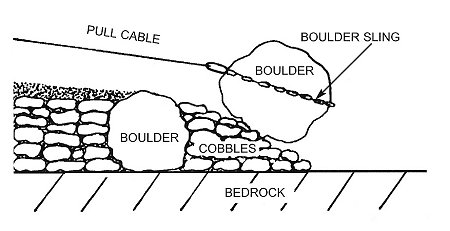

It takes a tremendous amount of winching-power to pull a boulder up and over another boulder from a dredge hole. The direction of pull is all wrong, and the second boulder will act like a barrier. The winching is much easier, smoother, and far less dangerous, if a ramp is built so the boulders will have an inclined runway to be pulled along. Cobbles can be used to make an effective boulder ramp. Therefore, an important part of setting up your dredge hole for winching is to construct a ramp/runway that can be used to easily remove the boulders, without them encountering difficult obstructions.

It can be really tough to pull a boulder out of a hole without a ramp.

Cobbles can be used to make an effective ramp for winching boulders out of a dredge hole.

One approach to setting up your hole is to dredge around a number of boulders as much as possible to free them up for winching. This way, more boulders can be pulled out of the hole once winching is begun. Then you can come back later to clean up the bedrock with your dredge.

To perform winching effectively, you will need plenty of air line attached to your hookah system. This is because it is necessary for the diver to sling each boulder and follow it to its final destination where he will disconnect it. Then, the sling and cable must be pulled back and attached to the next boulder. Since this process requires a lot of movement, depending upon the distance involved, you may need to attach an extension onto your air line to accomplish this smoothly.

FEASIBILITY OF MOVING BOULDERS

A dredging operation that requires a lot of boulders to be winched is going to move slower than if little or no winching is required. A winching operation almost always requires the involvement of at least one other person, sometimes even two or more. Those “extra hands” will usually expect to get something for their active participation in your dredging project. So you will find that when you need to use a winch, you will be moving slower through the pay-streak, and it will usually cost more to run the operation. Therefore, a pay-streak that has lots of boulders usually needs to pay pretty well to make the additional effort worthwhile.

The following video segment will give you a look at an organized winching program where multiple persons were involved:

Sometimes, you may discover an excellent pay-streak, but find that it lies beneath many boulders that have to be moved. Even though there may be plenty of gold under the boulders, after figuring the time and expense involved in winching, you may conclude that the gold recovery, though excellent, is still not sufficient to make the project economically feasible. Big boulders are not easy to move. Moving them takes time and money; more, sometimes, than the gold is worth. So, to avoid getting bogged down in an unworthy project, keep track of your daily expenses and your daily gold recovery. Then you will have some basis for calculating whether it is financially worthwhile to continue dredging in that specific location.

If your winching helpers are not full-timers on your dredging operation, and if the location is not too remote, you might arrange to have them arrive at a certain time each day to help pull boulders. That way, you can spend the morning setting up the hole to winch as many boulders as possible. Then, when your help arrives, the boulders can all be winched out of the hole at one time. After winching is completed for the day, you can let your winch helpers go, while you go back down and clean up the hole with your dredge. This way, you are not paying helpers to stand around with nothing to do while you are dredging. It can make a difference.

SETTING UP A WINCH FOR OPERATION

When you are using a portable power winch to move boulders in a dredging operation, the winch must be set up on a solid and stable foundation. It takes a tremendous amount of force to move a boulder. Sometimes, the boulder will move quickly. Or, sometimes, the sling will slip off the boulder, causing the cable to suddenly go slack. Maybe the boulder will loosen up and roll the wrong way, causing a sudden, heavy stress on the cable. When these things happen, and they do happen, you do not want your winch bouncing around or sliding off the platform. That could be extremely dangerous! The winch must be stable!

The winch also should be anchored to a solid object behind it which will hold its position much more securely than the boulders that are to be moved. A fair-sized tree, or a large boulder, directly behind the winch platform can work well for this purpose.

Also, the cable or chain being used to anchor the winch must be considerably stronger than the winch’s capability to pull. The last thing you need is your anchor chain or cable breaking while you are pulling a large boulder! This could cause the winch, and the winch operator, to be yanked off the platform, resulting in a serious accident. Undamaged, heavy-duty truck tow chains with the adjustable end-hooks are excellent for anchoring a winch. Make sure you get chains that are strong enough.

Your winch should also be anchored to a point which is lower than it is. If the winch is anchored from a low point, when boulders are being pulled, the winch will be held down more solidly onto the platform. If the winch is anchored to a higher point, during pulling the winch can be lifted off its platform. This can also be dangerous.

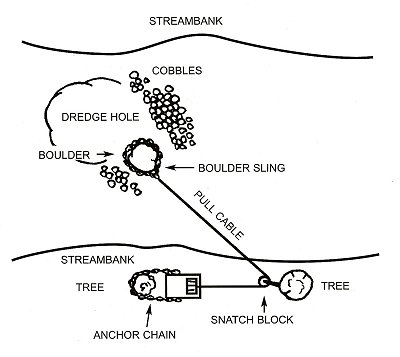

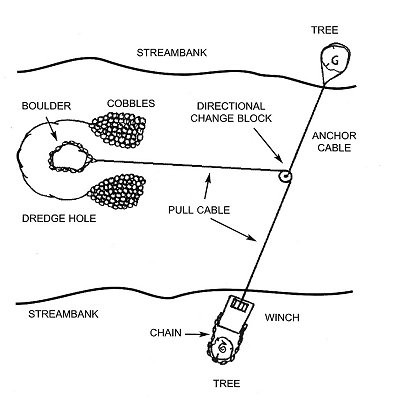

Sometimes, you will not be able to find a good location for your winch along the streambank. You prefer a location where the winch can be set up to directly face the boulders to be pulled, and which provides a level, solid foundation with a properly-located, fixed object from which to anchor the winch. But if that is not available, you can almost always find an acceptable foundation somewhere between two large objects along the bank. The platform may require a little concrete work to get it right. The winch can be anchored to one of the objects, while the other object can be used to attach a snatch block (heavy-duty pulley). The cable can then be run from the winch, through the snatch block, to the boulders that need to be moved. One advantage to this rigging setup is that if the cable does happen to break under a great strain, it will be less likely to fly directly at the winch and its operators.

Positioning the winch between two anchors on the bank,

because there is no easier way to get a straight pull with the winch.

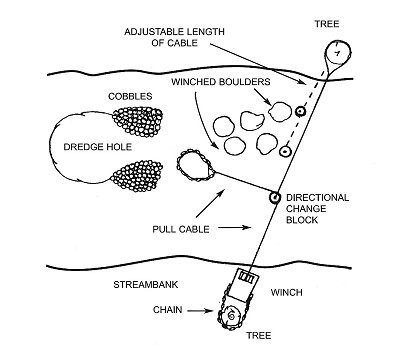

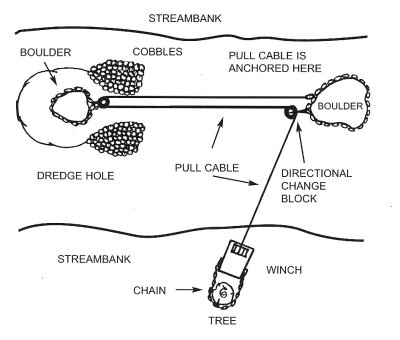

When you set up a winch, it is usually best to position it so the boulders will be pulled as much as possible in the desired direction. The boulders will also need to be pulled far enough away from the dredge hole that they will not have to be moved again at a later time. Often, you will not be able to set up the winch in a position where you can directly pull the boulders in the desired direction. For example, you may want to pull them downriver, rather than toward the stream bank. This situation is most commonly corrected by using directional-change snatch blocks. A snatch block (pulley) can be anchored at a point from the exact direction that you want to pull boulders. The cable then runs from the winch, through the snatch block, to the boulder. In this way, you can usually move the boulders in any direction that you desire from a stable winching position along the bank.

Setting up the proper direction of pull by anchoring a snatch block directly downstream in the river.

Directional-change blocks for winching should be very heavy-duty. They need to be stronger than the cable being used, or the capability of the winch to pull. The best pulley is one that can be quick-released from the cable. This way, you do not have to feed all the cable through the block to get rigged for winching. Good winching pulleys are generally available at industrial equipment supply stores and at marine equipment shops. Directional-change blocks can be attached to trees or boulders with the use of additional cable, chokers or heavy-duty chain. You will find that a few extra tow chains (long ones) and chokers will come in very handy when setting up a winching operation. Chains which have the end-hooks on them are best, so you can adjust their length to meet your needs.

To minimize damage to the environment, you can place pieces of wood between the cable or chain and the trunk of any tree that you use as an anchor. When you anchor a directional-change block to a tree or boulder, you are almost always better off anchoring to a low point. This will reduce the chances of rolling the boulder over or pulling down a tree.

When you use a cable to anchor a winch or directional-change block to a boulder, set it up so that the pull will not cause the cable to become pinched (between two boulders or between a boulder and the bedrock) or be pulled into the material underneath the boulder. Otherwise, after the winching, you may have trouble retrieving your cable without having to move the anchoring boulder as well.

At times, you may need to set up a directional-change block, to pull boulders in a desired direction, but cannot find a downstream boulder that is large enough to use as an anchor. In this case, you can run an additional cable out from a fixed object further downstream on the opposite side of the waterway, and attach your directional-change block to the cable. Then, by increasing or decreasing the length of the cable, you can position the block right where you want it.

Setting up a directional-change block by extending it out on a cable from the other side of the waterway.

It is not a good idea to winch boulders with rope, even the smaller boulders being pulled by your truck or a come-along. When you use rope for winching, the rope stretches even if it is doubled-back multiple times for extra strength. And, it stretches. And, it stretches. Then, it breaks. Such breaks can be dangerous when working around boulders. Also, it can quickly exhaust your supply of rope. Rope is just not strong enough for the job. Steel cable is best. You might get a deal on good, used steel cable from the scrap metal yards. Call around to find out who has it when you need it. Scrap yards usually sell it at scrap prices, by the pound, even if it is in good condition.

The cable you use on your winch should always be considerably stronger than your winch’s pulling capacity. The last thing anyone wants to see is a bunch of out-of-control steel cable flying wildly back in his direction. Faulty or worn cable should be replaced immediately and never used thereafter for winching.

Winching boulders involves an incredible amount of force. So does hauling logs by cable. Similar cables are used in logging operations to pull trees to the loading area. I have heard stories of logging cables snapping, flying back, and cutting a man in two. You are dealing with a similar amount of force when winching the larger boulders in a dredging operation.

WINCHING SIGNALS

During a winching operation, it will be necessary to have a diver in the water to set the sling on the boulders. The diver will also need to remove the sling from each boulder after it has been moved, and then return the sling and cable back to the dredge hole for use in moving the next boulder. This process will continue until all the boulders for that stage of the dredging operation have been moved.

Unless the diver is slinging boulders and operating the winch (a very slow way to go, unless the controls to the winch are in the water with the diver), another person must operate the winch, truck or other device that will be doing the pulling. Once you have more than one person involved in the operation, communication becomes a critical part of the process.

If the winch is a smaller one, or if a truck is being used to pull boulders, and the pulling position is in sight of the target boulders, the job might be accomplished with only one winch operator. On the other hand, in a normal two-man operation, if the winch operator is unable to maintain constant eye contact on the area where the winching is taking place, perhaps a third person will be needed to help with the communication. Each situation will be different. Since this need for immediate and accurate communication is a safety matter which requires on-site judgment, you will have to decide how many people are needed to winch safely.

Sometimes a truck can be turned around to pull backwards, and the driver can directly see and simultaneously carry out the diver’s signals. The controls on an electric winch will often allow a second person to be positioned well enough to see what is happening where the rocks are being moved.

While a boulder is being moved, the diver can watch its progress and signal the winch operator to stop pulling and/or give slack on the line so the boulder sling can be adjusted, if necessary, to successfully complete the movement as planned. The main point is that the diver must be able to communicate to the winch operator quickly and without error. The greater the pulling-power and/or speed of the winch, the more important it is that these signals be accurately received and acted upon quickly. Imagine that you are using a powerful winch to pull a large rock with a heavy steel cable and solid anchoring objects. If your boulder gets jammed against something else in the dredge hole so that it will not move, and you continue pulling with great force, something is eventually going to give. And, it might not be the boulder! This uncertainty is what you want to avoid.

If you are using a winch that does not automatically feed the cable evenly onto the drum, the operator will sometimes need to manually guide the cable. Otherwise, on hard pulls, if the cable starts crossing itself and is allowed to pinch itself on the drum, it may become damaged and thereafter be dangerous for further winching. For this reason, the winch operator may need to focus some attention on the winch, rather than on the diver. In this type of situation, it is wise to include an additional person to help relay communication. Someone needs to be watching for the diver’s signals at all times.

Gasoline-powered winches make noise. So does a gasoline-powered hookah-air system supplying air to the diver. The diver also usually has a regulator in his mouth. With all of this noise present, and the diver having his mouth full, verbal signals are usually not very dependable – especially, if there is a substantial distance between the diver and the winch operator. For these reasons, I have often found visual signals to be more trustworthy, particularly when there is a person positioned at the winch to relay the diver’s signals to the winch operator.

In shallow water, hand signals can usually work pretty well. You really only need three of them: “PULL” , “STOP” and “GIVE SLACK ON THE CABLE”. I highly suggest you take a look at the standard set of signals that my partners and I use in our own dredging operation. These can be found in a special video segment included with an article I wrote about teamwork. Otherwise, create your own signals so that they can be quickly and clearly understood, and one signal cannot be confused with another. There is also a section on winching and signals in my video, “Advanced Gold Dredging & Sampling Techniques.” You might want to check it out to get some ideas.

At times, you may be faced with the need to winch boulders out of a dredge hole located in deeper water. In this case, the diver will be heavily weighted down to stay on the river-bottom. He may also be some distance from the streambank. In this setting, it may be nearly impossible for the diver to surface to give timely signals to the winch operator. The process of getting up to the surface can simply take too long! When this is your situation, and if the water is not moving too fast, you may consider using a buoy, tied to a rope that is anchored near the dredge hole, to relay your signals. I personally have found the best and safest signals to be: (1) buoy underwater means, “PULL” (2) buoy floating at the surface means, “STOP PULLING” and (3) buoy bobbing up and down in the water means, “GIVE SLACK”.

This method of buoy-signals is relatively safe. If the buoy is anchored a short distance from the boulder, in order to pull the buoy underwater and hold it there, the diver would have to be away from the boulder on the “PULL” signal. If the buoy is floating, the diver can be anywhere, which is why it is the best choice for the “STOP” signal. You need to make certain, however, that nothing is allowed to snag the buoy’s rope (like the pull cable or an air line) which could pull the buoy underwater and cause a false “PULL” signal!

One other safety note:All divers must always watch their own hookah air lines during winching, to make sure an air line (or the signal rope to the buoy) is not snagged up in the cable or rolled over by the boulder as it is moved.

BOULDER SLINGS

When slinging boulders, try to make sure the pull cable will not rub too heavily or get crushed against other boulders. It is always best to protect the pull cable and let the boulder sling take the pounding. The boulder sling is going to be pounded anyway. Because of this rough duty, boulder slings should be replaced or repaired periodically.

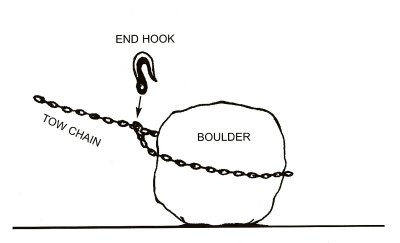

One type of boulder sling often used out in the field is a long, heavy-duty tow chain with end-hooks which allow the chain to be quickly and easily adjusted to any length. This system gives you a fast set up. Just wrap the chain around the boulder in the proper place, connect the end-hook to give you the right fit, and she’s ready to go.

Tow chain boulder sling with end hook.

However, some boulders are smoother and rounder, which makes it more difficult to get a good “bite” with a sling made out of chain. Every time you start to pull, the boulder might move just a little and then the chain slips off. You can waste a lot of time working on a single boulder in this way; it can get quite frustrating.

Logging cable-chokers are also useful for making a cable sling that will tighten up on the boulder as you pull. This may improve the situation, but still not work problem-free on smooth, round rocks.

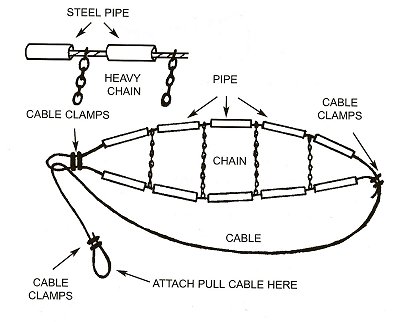

For round and smooth boulders, I have found the best remedy to be an auxiliary “boulder harness.” This homemade boulder harness consists of heavy cable, chain, steel pipe and cable clamps. It is very easy to construct. The sections of steel pipe slide onto the cable to protect it and to keep the cross-chains properly positioned. The harness is set up like a lasso. It pulls tighter around the boulder as stress increases on the line. And, it generally works well in pulling even the most difficult boulders.

How to put together an excellent boulder harness for winching.

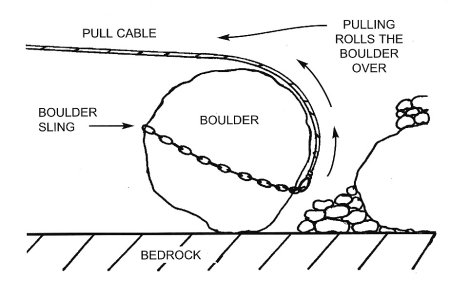

PULLING BOULDERS

Some boulders come easy and some do not. A lot of the problem is in breaking the boulder’s initial suction/compaction in the streambed. If your winch does not have the power to pull a boulder the way you have slung it, sometimes you can break the boulder free by using a rolling hitch A “rolling hitch” is rigged by slinging the boulder backwards, then running the chain or cable over top of the boulder. This places the winch’s pulling-power along the most-leveraged position on the boulder. This will sometimes free a stubborn boulder by rolling it.

How to sling a rolling hitch.

When pulling boulders up and out of a dredge hole, you should pull them some distance away from the hole. Otherwise, if there are more boulders to be moved, they may begin backing up along your ramp and block the passage of any more boulders. This could require you to move them all again, which is a time-waster that you can avoid with proper planning in the first place. For example, take a look at the image at the beginning of this article. That is a top view of a winching operation we did on one of our Group Mining Projects a short while ago. See how we were pulling the boulders back well out of our ongoing excavation?

If you are dealing with relatively deep streambed material and a lot of boulders, you may want to set up an adjustable, directional-change block behind the hole. This way, the boulders can be winched out of the hole in several different directions. This will prevent them from backing up so quickly.

Setting up an adjustable directional-change block to pull boulders in several different directions.

Once the dredge hole has been opened enough, some of the boulders can be winched or rolled to the backside of the hole, rather than taking them up the ramp. Winching will start to go faster when you get to this stage. Depending upon the situation, it may be necessary to winch some of the boulders up the ramp and out of the hole to prevent too much jamming. Be sure to keep access to the ramp free and clear. Otherwise, you may get closed in with too many boulders in the rear of your hole. The more boulders that are jammed up, the more difficult it can be to clear them out of the hole.

Sometimes, when you have winched your boulder to its destination, it will end up on top and pin your sling underneath. If you are using a tow chain as your sling, you can usually just unhook it and have the winch pull it out from underneath the boulder. But, if you are using a sling made of cable, you may not be able to pull it out from under the rock without damaging the harness. For this reason, it is a good idea to have a second sling on hand to help move the boulder off the other harness when this happens.

DIVER’S SAFETY

A diver will be safest by staying well away from the area where a boulder is being winched, and the path it will be taking as it is being pulled. The forces involved in winching are more than enough to cause a very serious accident. Since the diver is underwater, the winch operator sometimes cannot see what is happening where the bolder is located.

What can happen down there, though, is when the diver sees the boulder getting hung up on things as it is being pulled along, he wants to move in and help it along with his pry bar. The less power that your winch provides, the more the diver will naturally feel the need to help the boulder along in this way. Never forget that your safety margin is considerably reduced when you get near a boulder while it is being pulled! A safer course of action would be to stop the pulling and reset the harness, or reset the direction of pull, or improve the boulder ramp, or find a stronger winch for the job. Or, you can increase the pulling power of your existing winch by double blocking…

DOUBLE BLOCKING

“Double blocking” is accomplished by attaching a snatch block to the boulder sling, running the pull cable through that block, and then back to the last directional-change anchor. This type of rigging will nearly double the amount of pulling force that can be exerted against the boulder by the winch and pull cable.

Double blocking back to the last directional-change anchor

will nearly double the winch’s pulling power against the boulder.

If even more power is needed, another block can be set up on the line to run the pull cable back to the boulder sling. The pulling force of any winching device can be increased by continuing to double block in this way. There is a disadvantage to all this rigging, however. It takes much more cable to pull boulders any significant distance. Also, it is equally more difficult for the diver to pull the boulder sling and cable back to the dredge hole after each boulder has been moved. With all that cable going back and forth, it can get pretty complicated – especially if you are dealing with a limited amount of visibility. Quick-release snatch blocks are a must when double blocking. This way, you can detach the pulleys from the cable without having to feed it all the way through.

Actually, one double block is not that hard to manage as long as you have enough cable. It is when you double block a second time that it starts getting difficult to keep track of which cable is going to where? But, this alternative is available to you if you need the extra pulling power to move a particularly large boulder.

Directional-change blocks, by themselves, do not give you an increase in pulling power. For a power increase, the cable must be doubled back so that the boulder is moved only half the distance that the winch is pulling on the cable.

As I have explained elsewhere, I believe it is necessary to direct finer-sized material over lower-profile riffles that will continue to remain fluid under a mild flow of water, even when they are full of concentrated (heavy) material. If you have not reviewed the theory on this, I strongly suggest you read “The Size of Riffles.”

As I have explained elsewhere, I believe it is necessary to direct finer-sized material over lower-profile riffles that will continue to remain fluid under a mild flow of water, even when they are full of concentrated (heavy) material. If you have not reviewed the theory on this, I strongly suggest you read “The Size of Riffles.”

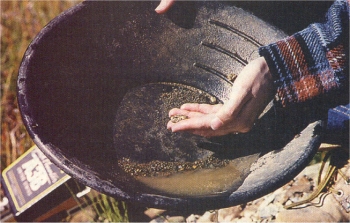

We invested quite a lot of time and energy into the prototype. All you have to do is look at how much (very fine) gold we found on that river in

We invested quite a lot of time and energy into the prototype. All you have to do is look at how much (very fine) gold we found on that river in

As an example, there is an overwhelming amount of heavy black sand and small iron rocks (and lead) along the

As an example, there is an overwhelming amount of heavy black sand and small iron rocks (and lead) along the

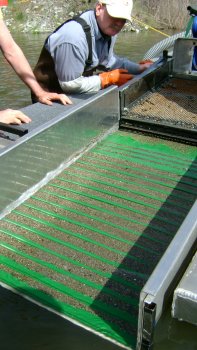

This image shows two sluice underlays following the header section (with no screens on top)

This image shows two sluice underlays following the header section (with no screens on top)

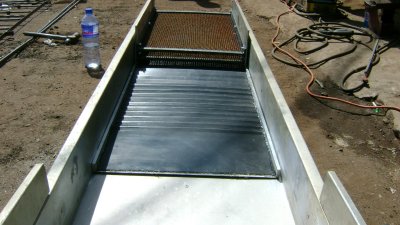

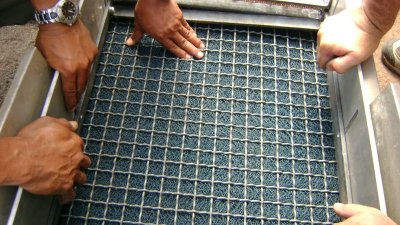

We finally found the right combination by using a wide, raised expanded metal over top of deep ribbed rubber matting. The aggressive expanded metal was dropping the gold out of the classified feed. Once it was in the ribbed mat, the gold was

We finally found the right combination by using a wide, raised expanded metal over top of deep ribbed rubber matting. The aggressive expanded metal was dropping the gold out of the classified feed. Once it was in the ribbed mat, the gold was

These add up to some weight; so you have to plan how to divide your sluice box into small-enough sections that you can lift the screen assemblies out of your sluice box without too much trouble. On the other hand, you want to minimize how many sections you have to make, because these are

These add up to some weight; so you have to plan how to divide your sluice box into small-enough sections that you can lift the screen assemblies out of your sluice box without too much trouble. On the other hand, you want to minimize how many sections you have to make, because these are  You have to use aluminum plate for the sides to keep the overall weight of the screen assembly from adding up too much. The height of the sides needs to be at least as tall as your sluice box. I build mine high enough that I have room to adapt a latch to snap everything down tight.

You have to use aluminum plate for the sides to keep the overall weight of the screen assembly from adding up too much. The height of the sides needs to be at least as tall as your sluice box. I build mine high enough that I have room to adapt a latch to snap everything down tight.

We have had good luck cutting the screens to size using a cutoff wheel on a hand-held grinder. If your side rails are made of thick material, you should be able to cut the screen to size and weld it down directly on top of the side rail frame. Grind all the edges nice and smooth, so your hands are not getting cut up once you start working with these screens on your dredge.

We have had good luck cutting the screens to size using a cutoff wheel on a hand-held grinder. If your side rails are made of thick material, you should be able to cut the screen to size and weld it down directly on top of the side rail frame. Grind all the edges nice and smooth, so your hands are not getting cut up once you start working with these screens on your dredge.

Possible need for added floatation: As I mentioned above, these double-screen assemblies are heavy. So if you do a refit of your sluice, you may also consider adding some floatation to your dredge. When I refit the original 6-inch Precision dredge for Cambodia (image above), I also had new, larger aluminum pontoons made up to provide enough floatation so that I could also stand on the dredge while it was running. Nice!

Possible need for added floatation: As I mentioned above, these double-screen assemblies are heavy. So if you do a refit of your sluice, you may also consider adding some floatation to your dredge. When I refit the original 6-inch Precision dredge for Cambodia (image above), I also had new, larger aluminum pontoons made up to provide enough floatation so that I could also stand on the dredge while it was running. Nice!

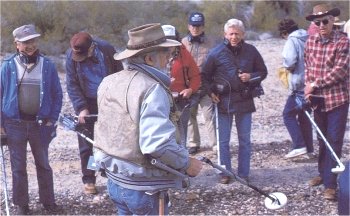

The title of this article can mean different things to different people and thereby add to the mystique surrounding the entire field of metal detecting, for that is what “Electronic Treasure Hunting” is all about. The word electronic should mean the same to everyone. What goes on in that metal box may be a mystery to most of us, but we all know it isn’t magic.

The title of this article can mean different things to different people and thereby add to the mystique surrounding the entire field of metal detecting, for that is what “Electronic Treasure Hunting” is all about. The word electronic should mean the same to everyone. What goes on in that metal box may be a mystery to most of us, but we all know it isn’t magic. I first wanted one when I read about a million-dollar nugget found in Australia by an “

I first wanted one when I read about a million-dollar nugget found in Australia by an “

When larger rocks are pushed through a sluice box by water force, they also create greater turbulence behind the riffles as they pass over, which may cause an additional loss of fine gold.

When larger rocks are pushed through a sluice box by water force, they also create greater turbulence behind the riffles as they pass over, which may cause an additional loss of fine gold.

It takes an incredible force of water to move boulders in a river. Once they are moving in a

It takes an incredible force of water to move boulders in a river. Once they are moving in a  One of the most useful tools that can help a dredger move boulders is a 5-foot (or longer) steel pry bar. If a boulder is too large to be moved to the rear of the dredge hole by hand, it can sometimes be rotated around to one side so that you can dredge out from under part of it. Then, it can be rotated around the other way to access the remaining gold and material beneath. A long pry bar can be a

One of the most useful tools that can help a dredger move boulders is a 5-foot (or longer) steel pry bar. If a boulder is too large to be moved to the rear of the dredge hole by hand, it can sometimes be rotated around to one side so that you can dredge out from under part of it. Then, it can be rotated around the other way to access the remaining gold and material beneath. A long pry bar can be a  Also beware of fractured bedrock walls that tower over you. They can fall apart and drop in your dredge hole as you remove the streambed material that holds them in place.

Also beware of fractured bedrock walls that tower over you. They can fall apart and drop in your dredge hole as you remove the streambed material that holds them in place.  When conditions are right for it, using a vehicle to pull smaller boulders can be much faster than using a come-along. One person operates the vehicle, while a diver is in the water, slinging the boulders. Safety becomes a greater concern when more than one person is involved in the pulling and the slinging of rocks. Communication and coordination between the “puller” and the “slinger” are very important to prevent serious accidents. Suggestion: If you turn the truck around and pull in reverse, you can better-see signals from your partner, and sometimes you get better traction, especially on a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Another suggestion: It is better to keep your vehicle a respectable distance from any drop-offs (like into the waterway), just in case the boulder gets momentum in the wrong direction. I know of guy who got pulled over the side of an embankment by a boulder gone wild!

When conditions are right for it, using a vehicle to pull smaller boulders can be much faster than using a come-along. One person operates the vehicle, while a diver is in the water, slinging the boulders. Safety becomes a greater concern when more than one person is involved in the pulling and the slinging of rocks. Communication and coordination between the “puller” and the “slinger” are very important to prevent serious accidents. Suggestion: If you turn the truck around and pull in reverse, you can better-see signals from your partner, and sometimes you get better traction, especially on a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Another suggestion: It is better to keep your vehicle a respectable distance from any drop-offs (like into the waterway), just in case the boulder gets momentum in the wrong direction. I know of guy who got pulled over the side of an embankment by a boulder gone wild!

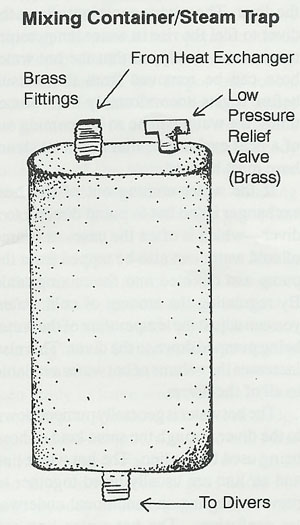

As far as I’m concerned, if you are going to dredge long hours in cold water, a hot water system is definitely the way to go! Water is usually heated with a heat-exchanging device mounted to the cooling or exhaust system of the dredge motor. The dredge pump is tapped to provide a water supply, which runs through the heat-exchanger, then through a steam trap/mixing tank, and then down through a hose to pour a constant volume of warm water into the dredger’s wet-suit. Some dredgers are using propane continuous-demand hot water heaters, but most use heat exchangers mounted to their engine exhaust systems.

As far as I’m concerned, if you are going to dredge long hours in cold water, a hot water system is definitely the way to go! Water is usually heated with a heat-exchanging device mounted to the cooling or exhaust system of the dredge motor. The dredge pump is tapped to provide a water supply, which runs through the heat-exchanger, then through a steam trap/mixing tank, and then down through a hose to pour a constant volume of warm water into the dredger’s wet-suit. Some dredgers are using propane continuous-demand hot water heaters, but most use heat exchangers mounted to their engine exhaust systems. The mixing container must be large enough to absorb a shot of extremely hot water, but not so large that it allows the water to cool down before it is pumped to the diver. The mixing container allows the diver to feel the rise in water temperature much more slowly, so that the hot water hose can be removed from the wetsuit before it gets uncomfortably hot. Sometimes, the water can be so hot coming out of a heat exchanger, that a special steam hose must be used. In fact, just for safety, I always use heat hose on the connection from the heat exchanger to the mixing tank.

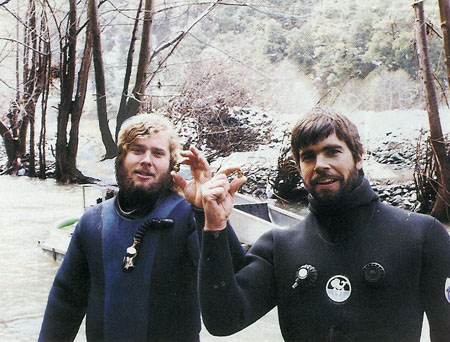

The mixing container must be large enough to absorb a shot of extremely hot water, but not so large that it allows the water to cool down before it is pumped to the diver. The mixing container allows the diver to feel the rise in water temperature much more slowly, so that the hot water hose can be removed from the wetsuit before it gets uncomfortably hot. Sometimes, the water can be so hot coming out of a heat exchanger, that a special steam hose must be used. In fact, just for safety, I always use heat hose on the connection from the heat exchanger to the mixing tank. Author was developing some of the early hot-water heaters on his first dredge in 1981 while working in the frigid waters of the Trinity River in Northern California.

Author was developing some of the early hot-water heaters on his first dredge in 1981 while working in the frigid waters of the Trinity River in Northern California.

Even if you are able to handle most of the cold water problems with the use of good equipment, another factor winter dredgers often have to deal with is higher and faster water. While the higher water will allow you to mine further up on the edges of the river, in many areas it will prevent you from mining out in the

Even if you are able to handle most of the cold water problems with the use of good equipment, another factor winter dredgers often have to deal with is higher and faster water. While the higher water will allow you to mine further up on the edges of the river, in many areas it will prevent you from mining out in the  As a side note on this, my commercial dredging buddies and I ate

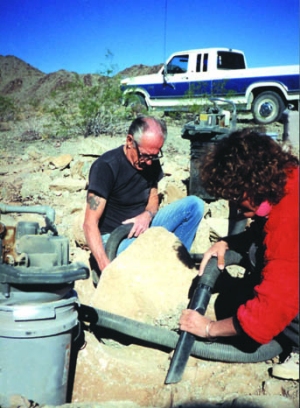

As a side note on this, my commercial dredging buddies and I ate  This is a picture that you will seldom see – me getting up at 5:30 a.m. full of excitement – to vacuum! Yet, I spent some of last summer and almost all of this past winter, doing just that. It wasn’t “dust bunnies” I was after, however; it was

This is a picture that you will seldom see – me getting up at 5:30 a.m. full of excitement – to vacuum! Yet, I spent some of last summer and almost all of this past winter, doing just that. It wasn’t “dust bunnies” I was after, however; it was  Finding new places to vack was not easy, as I have said. I have known for years, from experience, that the gold in the deserts isn’t always where it is supposed to be. What would look like great bedrock on the rivers often means nothing in the desert, mostly due to the lack of water volume and movement in the deserts. When I arrived at Quartzsite I met up with Al Powell, who is also a

Finding new places to vack was not easy, as I have said. I have known for years, from experience, that the gold in the deserts isn’t always where it is supposed to be. What would look like great bedrock on the rivers often means nothing in the desert, mostly due to the lack of water volume and movement in the deserts. When I arrived at Quartzsite I met up with Al Powell, who is also a