By Dave McCracken

Always set up a dry-washer downwind of where you are working!

Deserts consist of huge deposits of sedimentary material which have been affected by ancient ocean tides, ancient rivers, glaciers, floods, gully washers and windstorms. They are literally a gold mine of placer deposits.

There is also an enormous amount of gold-bearing mountainous dry placer ground which has remained relatively untouched by large-scale gold mining activity because of the scarcity of water required in those locations to support wet recovery methods.

Generally speaking, dry methods of gold recovery are not as effective or as fast as wet recovery methods. Yet, dry methods do work well enough that they can produce gold well if the ground is rich enough. Recent developments in dry washing equipment have made it possible for a one or two-man operation to work larger volumes of dry placer ground without water, and obtain good results in gold recovery.

Dry processing recovery systems generally use air flows to do the same job that water does in wet recovery systems. Under controlled conditions, air flows and mechanical motion and vibration can be made to effectively get rid of lighter, worthless materials. This causes a concentration of heavier materials similar to what occurs in wet processing.

SETTING UP TO WORK AN AREA

Sometimes a road can be bulldozed to your spot. Sometimes you can drive right in with a 2 or 4-wheel drive truck. In these situations, you might consider screening pay-dirt into the back of a truck and hauling it to a wash plant to be processed elsewhere. Actually, this is just slightly more difficult than shoveling directly into a wash plant. The hardest part is breaking the material away from the streambed and classifying it. It takes a little more time to haul the material to the wash plant, but that depends upon the distance and the condition of the road. It is also more difficult to shovel up into a truck. Some small operations use a portable conveyor belt to lift the material into their truck. Feeding the material from a truck into a wash plant is not as difficult, because it is usually down hill. An average one or two-person team should be able to move the equivalent of a pickup-sized load of screened pay-dirt and process it through a wash plant at another location in the period of a full day’s work-perhaps even two truckloads, depending upon the distances involved. If the material is paying well, they could do well at it, too.

DRY-WASHING PLANTS

If conditions do not allow you to truck the pay-dirt to a nearby water site to be processed by wet methods, you will have to consider processing the rich material by dry-production methods.

While dry-panning and winnowing do work, and have been broadly used as a means of production during the past, they are not normally as effective as some of the modern dry-washing plants which are available on today’s market.

Dry-washing machines use an air blowing fan or bellows-type device to blow a controlled amount of air-flow up through the dry material that is being processed. Air flows help blow off the lighter materials and allow the heaviest particles and gold to collect.

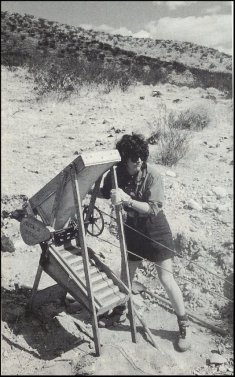

Dry-washing plants are available which can either be operated by hand or by lightweight engine and air-fan assemblies.

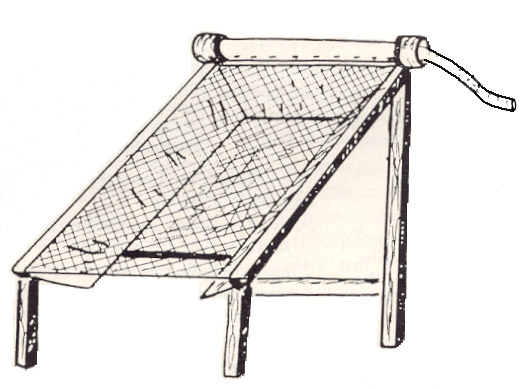

“Non-motorized dry-washing unit”

A hand-operated dry washing plant usually includes its own classification screen as part of the unit. Raw material can be shoveled directly onto it. The bellows air-blower is usually operated by turning a hand crank, which is often conveniently located so that one person can both shovel and alternately work the bellows at the same time. Under ideal conditions, two people working together can process up to a half-ton of gravel per hour by taking turns, one person shoveling while the other works the bellows.

Some units also have a 12-volt electric conversion kit to allow you the option to either hand-crank in the field or connect to a 12-volt battery for automatic bellows operation.

Various gasoline motor-driven dry concentrating units are available on the market which utilize static electricity and high-frequency vibration to help with gold recovery. Most commonly, there is a high-powered air-fan which pumps air through a discharge hose into the concentrator’s recovery system. The air currents which pass through the recovery system are adjustable so that the proper amount of flow of lighter materials through the recovery system can be obtained-similar to a sluice box in wet-processing. The purpose of the steady airflow is to “float off” the lighter materials through the box. Heavier materials like gold will have too much weight to be swept through the recovery system by the flow of air.

The bottom matting in this type of concentrator is usually made up of a specialized material which creates an electrostatic charge as high velocity air is passed through it from the air discharge hose. Fine pieces of gold, while not magnetic, do tend to be attracted to surfaces which have been electrostatically-charged, similar to the way iron particles are attracted to a magnet. So the bottom matting in these concentrators often attract fine particles gold to itself and tends to hold them there.

Some motorized dry concentrators also use a high-frequency vibrating device to keep the entire recovery system in continuous vibration while in operation. The way to get gold particles to settle quickly down through other lighter materials is to put the materials into a state of suspension. The vibrating device on this concentrator helps fine particles of gold work their way down through lighter materials that are being suspended by air-flows.

Here follows an excellent video demonstration which shows exactly how motorized dry concentrators work:

A motorized dry-washing machine is excellent for the production demands of a one or two-person operation. Under ideal conditions, it is able to process up to about a ton of raw material per hour, which is the equivalent of what a medium-sized wet sluicing operation can produce. This is as much or more than one or two people can usually shovel at production speed when working compacted streambed material. Most motorized dry-washers do their own screening of materials and almost everything else automatically. This leaves the operator free to produce at his or her own comfortable speed.

Total weight of the average motorized dry-washer is about 75 pounds, but the units do break down into separate pieces which can usually be carried around by a single person. So the electrostatic concentrator can be carried to a hot spot if it is worth a few trips to do so. They usually get about 3 hours to the gallon of gasoline.

SETTING UP A DRY-WASHER

There is no fixed formula for setting up the proper air flows and downward pitch on the recovery system of a dry-washer. A lot depends upon the nature of the material that you are processing, how heavy it is, whether or not the material is angular or water-worn and the purity (specific gravity) and size of the gold being recovered. Each of these variables is likely to affect how you must set your recovery system in each different place that it is operated.

The main thing to remember is that the machine needs to separate the gold from the lighter, valueless materials. If you only have a small amount of air-flow running through your dry-washer, then you will need more pitch on the recovery system-and you may need to feed the material slower. Too much air flow can also be a problem. Normally, you would compensate by adjusting to a lesser pitch on the riffle board.

Watch how the material flows over the riffle board. You should see the dirt rise up in an orderly fashion and flow over top of each riffle. It looks an awful lot like water. It is best to keep a steady feed of material going through a dry-washer at all times. The riffles should be filled about half to three-quarters, with a steady flow moving from one riffle to the next. The material in the riffles should have a fluid look to them; they should not be packed solid.

This following very important video sequence demonstrates how to set up and operate a motorized dry-washer, and it shows exactly what you should look for while making flow adjustments to obtain optimum gold recovery:

It is a good idea to shovel lower-grade material into your dry-washer while adjusting for the proper air flows and pitch. Once set, you can shovel in the pay-dirt.

One thing about dry-washing is that because it is generally slower than wet methods, the pay-dirt must have more gold. High-grade areas in the deserts certainly do exist! This is all the more reason to make sure your recovery system is set properly before processing pay-dirt. Chances are that you will not see any gold that might be discharged into the tailing pile through a dry-washer recovery system.

Another thing about setting up a dry-washing production program is that you always set up a dry-washer downwind of where you are working!

Once gold falls into the dead air space within the riffles, it will usually stay there. The air-flows are generally not strong enough to push gold out of there. There is a limit to this, however. Just like a water recovery system, a dry-washer will concentrate the heaviest materials which it processes. After some time, the heavier concentrates may require stronger air flows or a steeper pitch to keep them in suspension. At this point, it is probably time to clean up the recovery system and start all over again. If you are keeping a close eye on your recovery system, you can see when it is time to clean up. The fluidity of the material inside the riffles becomes more concentrated and slows down.

DRY-WASHING AND CLAY-LIKE MATERIALS

Material to be processed must be thoroughly dry to get the best results out of any dry-washing plant. Sometimes you will run into moist clays when out in the dry regions-just like you do in the wet streambed areas. It is also possible to find a pay-layer associated with the clay. Clays make dry-washing procedure more difficult, because they must be thoroughly dried out and broken up before being processed effectively by dry methods.

Sometimes this means the material needs to be set out in the sun to dry for a full day or more before anything further can be done with it. Sometimes it is necessary to dig clay a couple of days ahead of the processing stage. You can alternate spending a day digging and laying out material to dry, and then a day processing dried material. Sometimes, the dried clay can harden into clumps, which then must be broken down into dust and sand before you can recover the gold out of it. When necessary, all of these requirements require more time and energy. But if a good pay-streak is involved, you will find yourself doing whatever is necessary to recover the gold out of it.

It may be necessary to use rock-crushing machinery to break up hardened clay-like material and crush it down on any kind of a production -scale.

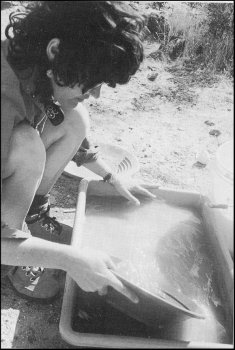

The clean-up of concentrates from a dry-washing plant is accomplished best by wet-processing methods. Usually, if you have room-enough to haul around a dry-washing plant in your vehicle, you will also have room for enough water to pan down your final concentrates, too. The following video sequence demonstrates how and when to perform a final clean-up during dry-washing:

If water is not available to you out in the field, the clean-up of your dry concentrates can sometimes be accomplished quite effectively by running them through your dry-washing plant several times. Final cleanup procedures can then be done to separate the gold from the last bit of remaining valueless material.

DESERT PLACER GEOLOGY

The chances of finding a hotspot out in the desert, or in some other dry region, are probably just as good or as your chances of finding a hotspot in the watersheds of the gold-bearing mountainous areas. These chances are pretty good, providing that you are willing to spend the time, study and work that is necessary to implement a good sampling plan.

Probably your best bet is to start off with a “Where to Find Gold” book and study the geological reports which apply to the area(s) of your interest. There has been some small-scale mining activity out in the dry regions. Much of it was lode mining, but some placer activity took place, as well. A good portion of prior activity is recorded information today. It can be of great value to you to know where gold has already been found. It is almost a sure thing that the areas which were once worked for gold at a profit were not entirely worked out. They might be worked again with today’s modern equipment at a profit. Any area which has once proven to pay in gold values is a good generalized area to do some sampling activity to see if additional pay-dirt can be found.

The desert areas were pretty-much left alone by the large-scale mining activities of earlier times because of the accessibility problem. Often, during earlier times, there was not enough water to sustain life, much less to process gold-bearing material.

But desert prospector should not limit him or herself to only the once-proven areas. Most of the desert regions have gone pretty-much untouched by past (effective) sampling activity because of accessibility problems, lack of water, and not having adequate equipment to do the job up until recent years. So the desert prospector has access to a lot of ground, and there are not that many competitors to worry about.

A single large rain or wind storm can change the entire face of the desert in just a few hours. There is very little undergrowth in these areas to prevent a good-sized rain storm from causing an incredible amount of erosion. And so you hear all the old-timers’ stories of finding bonanza-sized gold deposits, marking their position, going out after tools and supplies, and then returning to find the desert entirely changed and the bonanza apparently gone. Undoubtedly, some of these treasure stories are true. After all, many of those old-timers had gold to go along with their stories. Many of them spent the rest of their lives looking for their “lost gold mine.”

All of the placer geology concerning wet areas also applies to desert placer deposits (most which were developed during wet storm events). The same remains true of eluvial deposits-which is the gold that has weathered from a lode and been swept some distance away by the forces of nature. Eluvial deposits in the deserts (called “Bajada placers”) tend to spread out much more widely, and in different directions. This is because they are usually not eroding down the side of a steep mountainous slope. Therefore, they are sometimes a little more difficult to trace back to their original lodes. But it can be done. The answer is to do lots of sampling.

History has shown that one of the best locations to look for gold is where the hills meet the desert and fan out. This is where the water slows down during flood storms and drops gold in the gullies and washes. There also are likely to be more gold traps further up the hillside.

When doing generalized sampling in the desert, concentrate much of your activities in the washed-out areas, where natural erosion has cut through the sediments and created a concentration of heavier materials. Dry-washes, dry streambeds and canyons are good for this. Get an eye for the terrain, looking over the high points and the low points to get an idea of where the water flows during large flood storms. Areas where the greatest amount of erosion has taken place are areas where the highest concentration of gold values might be found. Remember that we are looking at many thousands of years of erosive impacts.

Bedrock will be exposed in some low areas, as in canyons and dry washes. These are ideal places for you to get into the lowest stratum of material-where the largest concentrations of gold values are often found. Large and small canyons have been formed by many years of erosion and are likely spots to find paying quantities of gold.

Caliche is cement-like false bedrock which is commonly found in desert placer areas.(photo USGS)

Caliche is cement-like false bedrock which is commonly found in desert placer areas.(photo USGS)

The desert and dry areas also commonly have a “false bedrock” layer specifically called “caliche.” Sometimes (often), this caliche layer is only a foot or two thick. In some areas, gold is concentrated along the caliche, just like on top of bedrock.

After a storm in the desert, in some places you can find small pockets of gold in the gravel traps, under rocks and under boulders which rest on top of the caliche. Sometimes the gold is pounded directly into the caliche and needs to be removed with a pick or crevice tool. Caliche layers which are close to the surface allow small-scale dry-washing operations to be economically feasible, because of the lesser amount of gravel and material which needs to be shoveled off the gold deposits.

Streambed material can be recognized by the smooth water-worn rocks. Anywhere in gold country, where streambed material is present, is a prime area to be doing some preliminary sampling. Such material indicates that it has been exposed to a substantial amount of running water. This means concentrating activity took place with those same materials. It is possible that the material was once washed out of an ancient river.

However, gravel and material does not need to be water-worn to carry gold in the desert areas. Rough and angular gravel, which has not been greatly affected by water, also sometimes carries gold in volume amounts. Testing is the key.

Sometimes it can be worthwhile to do some sampling in the different layers of desert material when they are present and exposed. Gold concentrations in and between flood layers can happen even more in the desert. This is because of the flash floods which can occur there.

Sometimes substantial gold concentrations can be found just beneath boulders which rest upon bedrock, or up in a layer above bedrock.

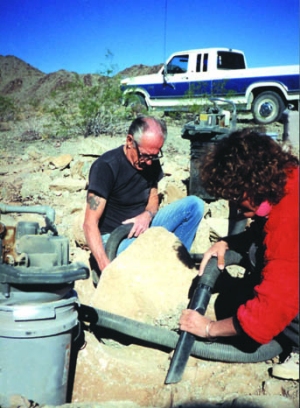

When you find a gold deposit in a dry area, whether on bedrock or the caliche, you will want to thoroughly clean the underlying surface upon which the gold is resting. Seldom will you visually see gold in dry placer material-even when there is a lot of gold present. Use a whisk broom or vack machine to clean all of the loose material. Sometimes, it is also productive to break up the surface of the caliche or bedrock with a pick or other crevicing tool.

Occasionally, in dry washes, you can actually see stringers of black sand along the bedrock or caliche-especially directly after a storm. You can sometimes do exceptionally well by following these stringers and digging out the concentrated gravel traps. Do not forget to test the roots from trees and other vegetation in such areas. Vegetation requires a certain amount of mineralization to grow. Roots can grow in and around high-grade gold deposits. I have heard of single roots which have been dug up and produced as much as three ounces of gold!

Some electronic prospectors use their metal detectors to trace concentrations of black sand. Then they follow up by testing the areas which produce the strongest reads from their detectors.

Some desert areas, like Quartzsite, Arizona, also have gold just lying around anywhere-even on top of the ground. Such places are excellent for electronic prospecting and dry-washing. The deserts of Australia are famous for this. I have a number of friends who have been very successful in the Nevada deserts, using metal detectors to recover large numbers of nuggets, some very large, directly off the surface of dry desert ground.

If you find a piece of gold on the surface of a dry placer area, it is likely that there are more pieces of gold in the immediate area. Electronic prospectors call these areas “patches.” Gold generally does not travel alone-unless it was dropped there by mistake.

Sand dunes in the desert are usually not very productive. This is because they mainly consist of lighter-weight sands that were deposited there by the wind. However, sometimes the wind can blow off the lighter-weight sands from a particular location, leaving the heavier materials exposed behind. This is similar to what happens after a big storm at the gold beaches. This is something that should be watched for.

When prospecting around in the dry areas, when you encounter tailing piles from past dry-washing operations, it might be worthwhile to do some raking of the tailings and scan around with a metal detector. Sometimes old tailing piles can be productive enough to run them through a modern dry-washer.

I remember, in my beginning days of prospecting, driving through the Upper Mojave Desert in Southern California, looking for mines to explore and tailings to scratch through. Occasionally, off to the sides of the road, I would spot small areas where dust and sand billowed up. At first, I thought that they must be “dust devils,” yet they never seemed to change position. In my imagination, I wondered if someone was sending up smoke signals, because that is what they appeared to resemble. One day, I decided to satisfy my curiosity and follow a dirt road up to the puffs of dust.

I remember, in my beginning days of prospecting, driving through the Upper Mojave Desert in Southern California, looking for mines to explore and tailings to scratch through. Occasionally, off to the sides of the road, I would spot small areas where dust and sand billowed up. At first, I thought that they must be “dust devils,” yet they never seemed to change position. In my imagination, I wondered if someone was sending up smoke signals, because that is what they appeared to resemble. One day, I decided to satisfy my curiosity and follow a dirt road up to the puffs of dust. My machine has

My machine has

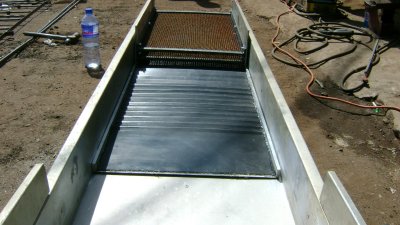

As I have explained elsewhere, I believe it is necessary to direct finer-sized material over lower-profile riffles that will continue to remain fluid under a mild flow of water, even when they are full of concentrated (heavy) material. If you have not reviewed the theory on this, I strongly suggest you read “The Size of Riffles.”

As I have explained elsewhere, I believe it is necessary to direct finer-sized material over lower-profile riffles that will continue to remain fluid under a mild flow of water, even when they are full of concentrated (heavy) material. If you have not reviewed the theory on this, I strongly suggest you read “The Size of Riffles.”

We invested quite a lot of time and energy into the prototype. All you have to do is look at how much (very fine) gold we found on that river in

We invested quite a lot of time and energy into the prototype. All you have to do is look at how much (very fine) gold we found on that river in

As an example, there is an overwhelming amount of heavy black sand and small iron rocks (and lead) along the

As an example, there is an overwhelming amount of heavy black sand and small iron rocks (and lead) along the

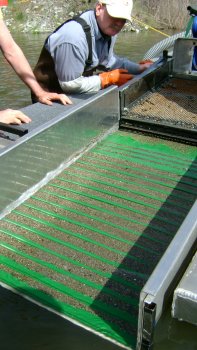

This image shows two sluice underlays following the header section (with no screens on top)

This image shows two sluice underlays following the header section (with no screens on top)

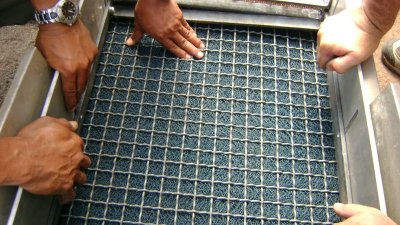

We finally found the right combination by using a wide, raised expanded metal over top of deep ribbed rubber matting. The aggressive expanded metal was dropping the gold out of the classified feed. Once it was in the ribbed mat, the gold was

We finally found the right combination by using a wide, raised expanded metal over top of deep ribbed rubber matting. The aggressive expanded metal was dropping the gold out of the classified feed. Once it was in the ribbed mat, the gold was

These add up to some weight; so you have to plan how to divide your sluice box into small-enough sections that you can lift the screen assemblies out of your sluice box without too much trouble. On the other hand, you want to minimize how many sections you have to make, because these are

These add up to some weight; so you have to plan how to divide your sluice box into small-enough sections that you can lift the screen assemblies out of your sluice box without too much trouble. On the other hand, you want to minimize how many sections you have to make, because these are  You have to use aluminum plate for the sides to keep the overall weight of the screen assembly from adding up too much. The height of the sides needs to be at least as tall as your sluice box. I build mine high enough that I have room to adapt a latch to snap everything down tight.

You have to use aluminum plate for the sides to keep the overall weight of the screen assembly from adding up too much. The height of the sides needs to be at least as tall as your sluice box. I build mine high enough that I have room to adapt a latch to snap everything down tight.

We have had good luck cutting the screens to size using a cutoff wheel on a hand-held grinder. If your side rails are made of thick material, you should be able to cut the screen to size and weld it down directly on top of the side rail frame. Grind all the edges nice and smooth, so your hands are not getting cut up once you start working with these screens on your dredge.

We have had good luck cutting the screens to size using a cutoff wheel on a hand-held grinder. If your side rails are made of thick material, you should be able to cut the screen to size and weld it down directly on top of the side rail frame. Grind all the edges nice and smooth, so your hands are not getting cut up once you start working with these screens on your dredge.

Possible need for added floatation: As I mentioned above, these double-screen assemblies are heavy. So if you do a refit of your sluice, you may also consider adding some floatation to your dredge. When I refit the original 6-inch Precision dredge for Cambodia (image above), I also had new, larger aluminum pontoons made up to provide enough floatation so that I could also stand on the dredge while it was running. Nice!

Possible need for added floatation: As I mentioned above, these double-screen assemblies are heavy. So if you do a refit of your sluice, you may also consider adding some floatation to your dredge. When I refit the original 6-inch Precision dredge for Cambodia (image above), I also had new, larger aluminum pontoons made up to provide enough floatation so that I could also stand on the dredge while it was running. Nice!

This is a picture that you will seldom see – me getting up at 5:30 a.m. full of excitement – to vacuum! Yet, I spent some of last summer and almost all of this past winter, doing just that. It wasn’t “dust bunnies” I was after, however; it was

This is a picture that you will seldom see – me getting up at 5:30 a.m. full of excitement – to vacuum! Yet, I spent some of last summer and almost all of this past winter, doing just that. It wasn’t “dust bunnies” I was after, however; it was  Finding new places to vack was not easy, as I have said. I have known for years, from experience, that the gold in the deserts isn’t always where it is supposed to be. What would look like great bedrock on the rivers often means nothing in the desert, mostly due to the lack of water volume and movement in the deserts. When I arrived at Quartzsite I met up with Al Powell, who is also a

Finding new places to vack was not easy, as I have said. I have known for years, from experience, that the gold in the deserts isn’t always where it is supposed to be. What would look like great bedrock on the rivers often means nothing in the desert, mostly due to the lack of water volume and movement in the deserts. When I arrived at Quartzsite I met up with Al Powell, who is also a  When I first heard about picking

When I first heard about picking  Finally, after many, many frustrating hours, the first nugget succumbed to my detector, minutes later, another. I really got excited, and I decided to share this new-found activity with my friends. I helped them learn what I had learned, and then we developed new methods and techniques. Detectors were getting better, and I purchased the latest equipment, knowing that I needed every edge that I could possibly acquire.

Finally, after many, many frustrating hours, the first nugget succumbed to my detector, minutes later, another. I really got excited, and I decided to share this new-found activity with my friends. I helped them learn what I had learned, and then we developed new methods and techniques. Detectors were getting better, and I purchased the latest equipment, knowing that I needed every edge that I could possibly acquire. It has never before been more possible to locate your own gold nuggets with the aid of a metal detector, than it is right now. It is not that there is more gold out there. In fact, each day, there is a little less. However, with the new instruments available today, millions upon millions of beautiful gold nuggets are now within easy reach of the intelligent, properly-equipped electronic prospector. You don’t need tons of equipment to haul around, nor do you need many thousands of dollars to get started. The exercise is mild; the air is fresh; and the pursuit of your own gold nuggets is done at your pace — no one else’s.

It has never before been more possible to locate your own gold nuggets with the aid of a metal detector, than it is right now. It is not that there is more gold out there. In fact, each day, there is a little less. However, with the new instruments available today, millions upon millions of beautiful gold nuggets are now within easy reach of the intelligent, properly-equipped electronic prospector. You don’t need tons of equipment to haul around, nor do you need many thousands of dollars to get started. The exercise is mild; the air is fresh; and the pursuit of your own gold nuggets is done at your pace — no one else’s.

When larger rocks are pushed through a sluice box by water force, they also create greater turbulence behind the riffles as they pass over, which may cause an additional loss of fine gold.

When larger rocks are pushed through a sluice box by water force, they also create greater turbulence behind the riffles as they pass over, which may cause an additional loss of fine gold.

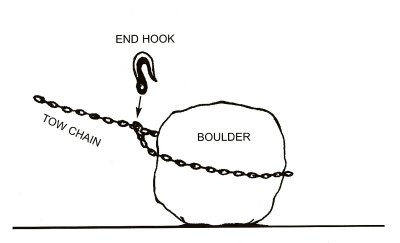

It takes an incredible force of water to move boulders in a river. Once they are moving in a

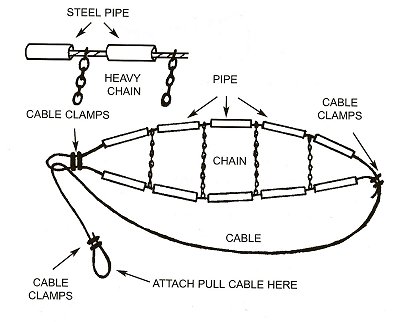

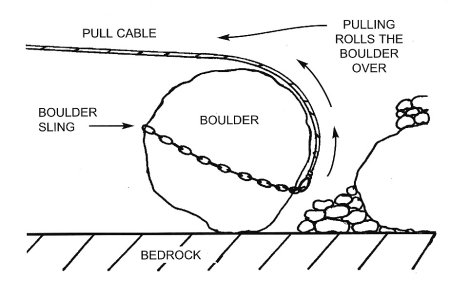

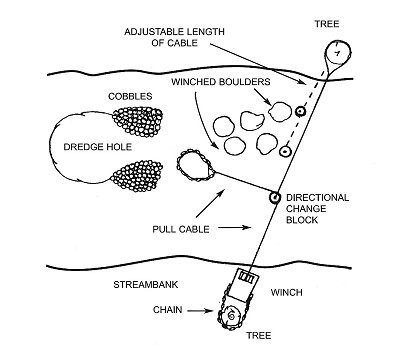

It takes an incredible force of water to move boulders in a river. Once they are moving in a  One of the most useful tools that can help a dredger move boulders is a 5-foot (or longer) steel pry bar. If a boulder is too large to be moved to the rear of the dredge hole by hand, it can sometimes be rotated around to one side so that you can dredge out from under part of it. Then, it can be rotated around the other way to access the remaining gold and material beneath. A long pry bar can be a

One of the most useful tools that can help a dredger move boulders is a 5-foot (or longer) steel pry bar. If a boulder is too large to be moved to the rear of the dredge hole by hand, it can sometimes be rotated around to one side so that you can dredge out from under part of it. Then, it can be rotated around the other way to access the remaining gold and material beneath. A long pry bar can be a  Also beware of fractured bedrock walls that tower over you. They can fall apart and drop in your dredge hole as you remove the streambed material that holds them in place.

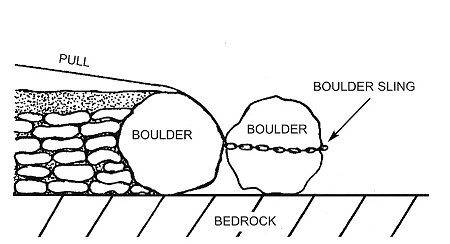

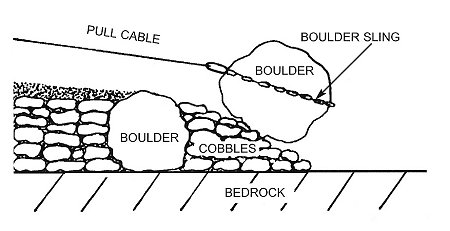

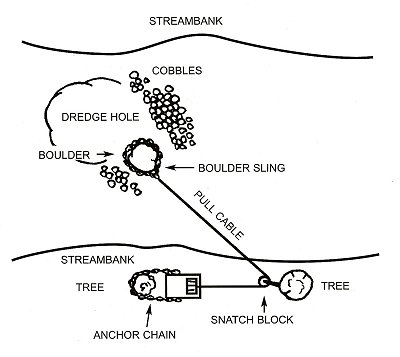

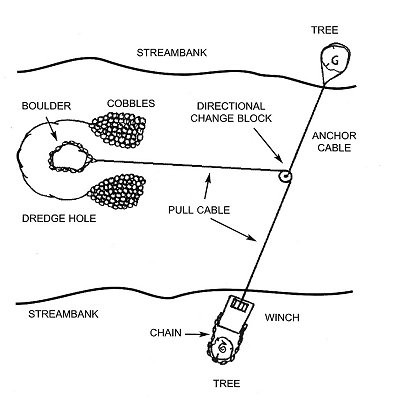

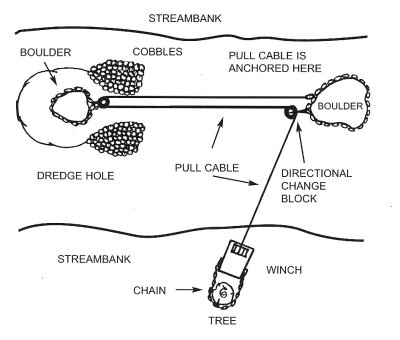

Also beware of fractured bedrock walls that tower over you. They can fall apart and drop in your dredge hole as you remove the streambed material that holds them in place.  When conditions are right for it, using a vehicle to pull smaller boulders can be much faster than using a come-along. One person operates the vehicle, while a diver is in the water, slinging the boulders. Safety becomes a greater concern when more than one person is involved in the pulling and the slinging of rocks. Communication and coordination between the “puller” and the “slinger” are very important to prevent serious accidents. Suggestion: If you turn the truck around and pull in reverse, you can better-see signals from your partner, and sometimes you get better traction, especially on a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Another suggestion: It is better to keep your vehicle a respectable distance from any drop-offs (like into the waterway), just in case the boulder gets momentum in the wrong direction. I know of guy who got pulled over the side of an embankment by a boulder gone wild!

When conditions are right for it, using a vehicle to pull smaller boulders can be much faster than using a come-along. One person operates the vehicle, while a diver is in the water, slinging the boulders. Safety becomes a greater concern when more than one person is involved in the pulling and the slinging of rocks. Communication and coordination between the “puller” and the “slinger” are very important to prevent serious accidents. Suggestion: If you turn the truck around and pull in reverse, you can better-see signals from your partner, and sometimes you get better traction, especially on a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Another suggestion: It is better to keep your vehicle a respectable distance from any drop-offs (like into the waterway), just in case the boulder gets momentum in the wrong direction. I know of guy who got pulled over the side of an embankment by a boulder gone wild!