I have been managing these weekend group mining projects for the past 26 years. All this experience has taught me that every single group has its own chemistry. There are probably a lot of different things that contribute to this; the different personalities, the weather, how the bigger world is doing at the moment, and perhaps even how I am feeling. But every group is different.

We always begin with a morning of theory on Saturday. This gives me an opportunity to size up the participants and the group-chemistry, organize things with my experienced helpers and provide a presentation of the long-proven procedures that we have developed to find gold. We call this a “sampling plan.”

These days, we do the initial meeting and the morning presentation at the Grange Hall in Happy Camp. Nearly everyone was already present there when I showed up at about 9 AM. And I knew even before I got out of my car that this was going to be a lively bunch. They were already having a lot of fun. This is all good; because my seasoned helpers and I know how to direct all that enthusiasm into the hard work which would be necessary later in the day, and especially on Sunday.

After going over the weekend plans and covering the theory on sampling, I always take time to answer everyone’s questions before we break for lunch. But this time, I had to cut it short with this lively group or we would not have had time for lunch! I know the participants are really into it when they are asking all the right questions.

Saturday afternoon found us all up at k-15A, otherwise known as the Mega Hole. This is one of our more popular high-banking areas. By high-banking, I am talking about mining up out of the water. We also have a very popular camping area at K-15A. This makes it convenient for participants to just walk down to the gravel bar where we are doing the project. K-15A is quite a long mining property. Over the many years, we have done plenty of weekend and week-long mining projects there, on both sides of the river. The property has been very productive for us, and we are lucky to have it.

On this particular project, we were up towards the upper-end of the property. We have been doing these weekend events there, because boats are not required when we have larger groups, and because there is this very distinct brown layer which is usually only a about a foot deep into the gravel bar. We get lots of nice gold right off the top of that layer!

I am lucky to have a bunch of experienced members who enjoy coming out and helping me to organize these events. With their help, we split the larger group into smaller ones, each with one of my helpers as a team leader. The team leaders went out and did some sampling in advance on Saturday morning, while the rest of us were still busy at the Grange Hall. So, when we showed up out on the gravel bar on Saturday afternoon, my helpers just pointed to several hot-spots where I could provide a sampling and gold panning demonstration. It’s always better if I turn up some gold in the sample. This gets everyone motivated to find more gold!

Participants get to keep any gold they find on Saturday afternoon. So after seeing the gold from my sample, this group went right to work. It wasn’t long before people started showing me the gold in their pans. For many, these weekend projects provide the first gold they ever found. “First gold” is always the most precious! I still remember my first gold. It didn’t come this easy! But it was still a very magic moment. So I enjoy this part as it unfolds, sharing the “first gold” moments with others, watching for the sparkle in their eye at the first moment of realization. I love my job!

Really, we were just going through the motions out there on Saturday afternoon. My helpers had already confirmed where we were going to dig on Sunday. So we devoted the afternoon assisting beginners to dial in their gold panning techniques. It’s not that panning is difficult. It just takes a little practice to teach your body the correct motions. This bunch was catching on fast!

As the afternoon progressed, we set up the high-bankers close to the places where we would dig pay-dirt. We wanted everything to be ready for an early start on Sunday morning. This is because we like to get most of the physical work done before the summer heat of the day sets in.

A high-banker is a portable sluicing device, like an aluminum trough with baffles (called riffles) along the bottom edge. Since gold is 5-to-6 times heavier than normal gravel and sand, it gets trapped in the riffles, while the lighter material is washed through by water. Because water is pumped to it, the recovery system of a high-banker can be set up close to the dig-site. This eliminates the need to pack the pay-dirt closer to water.

After getting everything set up, my helpers and I left to go get set up for the evening meal. There were a bunch of participants lagging behind out there still panning for gold. Some of them probably stayed until dark!

Nearly everyone met up back at the Grange Hall that evening to participate in our Saturday evening pot-luck. These pot-lucks are a tradition that dates all the way back to 1986 when we started The New 49’ers. Mostly, they are just get-togethers. Lots of members come. We have a great meal, enjoy each other’s company, exchange helpful information and do a prize drawing. Mostly we just have a good time.

Almost everyone was out on the bar ahead of me on Sunday morning. The team leaders had everyone organized, and Rich Krimm informed me that two or three hundred buckets of pay-dirt had already been processed. This was good! Man, there was a lot of productive activity going on. The enthusiasm was infectious. I’m not sure I have ever seen so many people having so much fun playing in the dirt! Here are some explanations of what was going on:

Since most of the work gets done before lunch on Sunday, we just encouraged the flow of material from off the top of that brown layer, into buckets, and through the high-bankers. The harmonious sound of picks, shovels, rocks being tossed out of the way and material being poured into the high-bankers is like music to my ears. There was a lot of laughing and joking going around. Morale was high out there. This always makes me feel good!

We don’t normally shut things down for lunch on Sunday. People just take breaks when they are ready. We usually only stop when the water pumps run out of fuel. This also gives us an opportunity to clean-up one of the high-grade portions a one of the high-bankers. A “high-grader” is a smaller portion of the high-banker that recovers perhaps about 50 percent of the gold. Because it can be cleaned up fast, you can get a good idea how an area is producing when you run production samples. A few hundred buckets is a pretty substantial sample!

Rich made quick work of recovering the gold from one of the high-graders. Then he made sure to take it around and show everyone out there on the work site. You would have thought we were at a sports event the way everyone was cheering. The hard work was really paying off!

We actually do this on every project so everyone can see how their physical energy is being converted into Mother Nature’s most-favored treasure – gold! This always motivates at least another few hundred buckets once the pumps get fueled up. But on this day, the group never stopped filling buckets even while we were preparing for a second run. They only stopped digging when they saw that others were cheering over the gold! The following video sequence captured how jacked up this bunch was:

So that we can be completely finished by dinnertime on Sunday, with everything put away and the gold split up, we like to end off on the dig by about noon. This was a real struggle with this group, because they just wanted to keep digging. I imagine some of them would still be out there digging if we didn’t shut the high-bankers down!

After cleaning out the high-banker recovery systems, we ran the concentrated material over a special “Le-Trap” sluice that we use to reduce the amount of iron with no loss of gold. It is always a treat to watch the gold accumulate in the riffles. Some of the participants were wondering where the ice cold beer was! But that would have to come later, since we were not yet finished with our day. Here are two video sequences which captured a Le Trap demonstration, and also the fun we were having during clean-up:

After back-filling the holes we had dug out on the bar, we made plans to meet back up at the Grange Hall where we would finish the clean-up and split the gold.

Let me just say that this is real mining. The participants get to assist in every step along the way. In addition to being part of the process, the experience rubs off on all the participants, allowing everyone the knowledge to do it on their own. I demonstrate the process exactly how I do it in my own mining programs.

Once we got it all separated and cleaned up, our work from several hours of hard work that morning produced 290 grains of gold, which is 6/10ths of an ounce. That’s around a thousand dollars, and it would have bought us plenty of beer. And pizza, too! There were also 21 nuggets, the largest being 6 grains. We split it all up evenly between the 43 participants, and I’m not sure I have ever seen a happier bunch of people!

High-banking in California this Season

While Oregon is more user-friendly towards suction dredging; our best high-banking opportunities remain along our extensive properties on the Klamath River in northern California. Therefore, Our Weekend Group Mining Projects will take place during 2012 near our headquarters in Happy Camp. They are scheduled as follows: June 2 & 3; June 23 & 24; July 14 & 15; August 4 & 5; August 25 & 26. These events are free to all active Members, and everyone is invited to attend. Please contact our office in advance to let us know you will be there: (530) 493-2012.

New Legal Fund Prize Drawing

We will be giving away 15 prizes in our new legal-fund raiser:

Grand Prize: 1-ounce American Gold Eagle

Four ¼-ounce American Gold Eagles

Ten 1/10th-ounce American Gold Eagles

The drawing will take place at our weekly potluck in Happy Camp on Saturday, 7 July (2012).

The girls in our office automatically generate a ticket in your name for every $10 legal contribution that we receive ($100 would generate 10 tickets, etc). There is no limit to the size or frequency of your contributions, or to the number of prizes you can win. Contributions can be called in to our office at (530) 493-2012, or they can be mailed to The New 49’ers, P.O. Box47, Happy Camp, CA 96039. Or you can do it on our web site by going here: Make a Donation

We greatly appreciate help from you in regenerating our legal fund!

2012 Group Insurance Policy

All Members are eligible to sign up for $10,000 of accidental medical Insurance which covers you while camping, prospecting for gold, and also during any activities which we sponsor. Dental accidents are included, along with $2,500 for accidental death or dismemberment. The policy has a $100 deductable. It is an annual policy which extends through January of 2013. This insurance is available for $30 per year, per person. More information can be found here.

Sign up for the Free Internet Version of this Newsletter: We strongly encourage you to sign up for the free on line version of this newsletter. The Internet version is better, because you can immediately click directly to many of the subjects which we discuss; because the on line version is in full color; because we link you directly to locations through GPS and Google Earth technology; and because you can watch the free video segments which we incorporate into our stories.

The New 49’ers Prospecting Association, 27 Davis Road, Happy Camp, California 96039 (530) 493-2012

www.goldgold.com

In

In  Several years then quickly passed by while the deposits we found during the

Several years then quickly passed by while the deposits we found during the  Since we were not using a

Since we were not using a  Dredging under a five-ton boulder (underwater estimated weight) and trying to calculate just how much you can take out to loosen it up enough to roll, without taking so much that it rolls in on top of you, is also a dangerous game. We call these boulders “Loomers.” It is a very high-risk job, because it is

Dredging under a five-ton boulder (underwater estimated weight) and trying to calculate just how much you can take out to loosen it up enough to roll, without taking so much that it rolls in on top of you, is also a dangerous game. We call these boulders “Loomers.” It is a very high-risk job, because it is  So I did not have my full attention on the state of the bedrock wall that was hanging over me. I noticed that it was fractured and the cracks were big. The problem was that we were dredging under a cave-like overhang of bedrock on the side of the river. We just had our best production days right behind us. I was watching out for big rocks on the working face, and I was paying a lot of attention to the gold I was seeing on the bedrock!

So I did not have my full attention on the state of the bedrock wall that was hanging over me. I noticed that it was fractured and the cracks were big. The problem was that we were dredging under a cave-like overhang of bedrock on the side of the river. We just had our best production days right behind us. I was watching out for big rocks on the working face, and I was paying a lot of attention to the gold I was seeing on the bedrock! I sincerely believe that if it is at all possible, it is best to stay in the immediate vicinity of a location in which you have suffered severe injury or fear until the immediate shock wears off. I feel the body and mind will heal itself faster, and I also don’t like to leave right away because it leaves me feeling like I am running away. I could see by the look in my partner’s eyes that he did not approve, but I insisted.

I sincerely believe that if it is at all possible, it is best to stay in the immediate vicinity of a location in which you have suffered severe injury or fear until the immediate shock wears off. I feel the body and mind will heal itself faster, and I also don’t like to leave right away because it leaves me feeling like I am running away. I could see by the look in my partner’s eyes that he did not approve, but I insisted. And now? I have dropped back on the pay-streak and have incorporated

And now? I have dropped back on the pay-streak and have incorporated

Please

Please

We believe that the future of small-scale prospecting could largely depend upon how effectively we as an industry pull together in a responsible way to meet the challenges which we will face together. Much of this effectiveness and dedication is contingent upon gaining exposure to existing operations which are already effective. This is because, generally, the more skilled you are as a gold prospector, the better your chances of realizing your expectations, ambitions, and goals. Moreover, it is generally true that if you are successful, you radiate your success to others and our entire industry flourishes and grows.

We believe that the future of small-scale prospecting could largely depend upon how effectively we as an industry pull together in a responsible way to meet the challenges which we will face together. Much of this effectiveness and dedication is contingent upon gaining exposure to existing operations which are already effective. This is because, generally, the more skilled you are as a gold prospector, the better your chances of realizing your expectations, ambitions, and goals. Moreover, it is generally true that if you are successful, you radiate your success to others and our entire industry flourishes and grows.

The New 49’ers provide all of the dredges, motorized sluicing equipment and boats used in these projects. Participants will need to have their own wet-suits (for those who will dredge) or other protective clothing and footwear, a dive mask and transportation. Participants provide their own lodging and nourishment.

The New 49’ers provide all of the dredges, motorized sluicing equipment and boats used in these projects. Participants will need to have their own wet-suits (for those who will dredge) or other protective clothing and footwear, a dive mask and transportation. Participants provide their own lodging and nourishment.

Most intermediate and larger-sized gold dredges come with built-in hookah-air systems. These attach to the same engine that powers the water pump. As demonstrated in the following video segment, air for breathing underwater is generated by an air compressor, passes down through an air line, and provides air to a diver through a regulator, similar to what is used by SCUBA divers:

Most intermediate and larger-sized gold dredges come with built-in hookah-air systems. These attach to the same engine that powers the water pump. As demonstrated in the following video segment, air for breathing underwater is generated by an air compressor, passes down through an air line, and provides air to a diver through a regulator, similar to what is used by SCUBA divers: The

The

A cutter-head will just get bogged down (and damaged) in a normal

A cutter-head will just get bogged down (and damaged) in a normal  If you want to do serious excavations with a suction dredge, you must leave the opening of the suction-nozzle as large in diameter as possible, while still reducing it enough to eliminate un-necessary

If you want to do serious excavations with a suction dredge, you must leave the opening of the suction-nozzle as large in diameter as possible, while still reducing it enough to eliminate un-necessary

A gold-dredger has an advantage, in that he or she is able to float equipment where he or she wants it to go, sucking up gravel (sampling) from various strategic areas. This is much easier than having to carry equipment around and set it up in each new area, as is required in conventional mining.

A gold-dredger has an advantage, in that he or she is able to float equipment where he or she wants it to go, sucking up gravel (sampling) from various strategic areas. This is much easier than having to carry equipment around and set it up in each new area, as is required in conventional mining. In fact, most of the work associated with suction dredging involves the organization and movement of cobbles and (sometimes)

In fact, most of the work associated with suction dredging involves the organization and movement of cobbles and (sometimes)

Running a successful mining operation is one thing. Helping someone else to be able to run a successful operation is something else altogether. During the past several years, we have

Running a successful mining operation is one thing. Helping someone else to be able to run a successful operation is something else altogether. During the past several years, we have  I personally know a fair number of successful gold miners; some who we worked with and some who learned on their own. Some are successful on a smaller-scale. Some mine gold to support themselves and their families.

I personally know a fair number of successful gold miners; some who we worked with and some who learned on their own. Some are successful on a smaller-scale. Some mine gold to support themselves and their families. One of the primary common denominators I recognize being present in successful miners alike is a never-ending drive, or hunger, or urge to get on and stay on the

One of the primary common denominators I recognize being present in successful miners alike is a never-ending drive, or hunger, or urge to get on and stay on the  I’m focused on being the world’s best underwater mining specialist–and on helping others, also, to be very good at it.

I’m focused on being the world’s best underwater mining specialist–and on helping others, also, to be very good at it. Successful people win their games by focusing themselves towards accomplishment within the rules of the game. Don’t like the rules? Do something effective to bring about agreement to have the rules changed. Winning the game by the rules brings great satisfaction, and successful people are willing to put out the necessary effort to gain each step along the way. Sure, it’s always a bit more difficult to not take the unethical short cuts which present themselves. But real progress is built upon a solid foundation of the ability to accomplish.

Successful people win their games by focusing themselves towards accomplishment within the rules of the game. Don’t like the rules? Do something effective to bring about agreement to have the rules changed. Winning the game by the rules brings great satisfaction, and successful people are willing to put out the necessary effort to gain each step along the way. Sure, it’s always a bit more difficult to not take the unethical short cuts which present themselves. But real progress is built upon a solid foundation of the ability to accomplish.

We use extra heavy-duty airline, the kind that does not kink under normal working conditions. I have tossed cobbles onto it hundreds or thousands of times; I have rolled boulders over it; and I have never had an instance where the airline was damaged in any visible way. That is, until this time.

We use extra heavy-duty airline, the kind that does not kink under normal working conditions. I have tossed cobbles onto it hundreds or thousands of times; I have rolled boulders over it; and I have never had an instance where the airline was damaged in any visible way. That is, until this time. Here are a few other pointers we have learned about airlines from our experience: Stay aware of where your airline is. Do not allow it to get wrapped and tangled around objects, the suction hose, tangled with other divers’ airlines. Immediately untangle your airline if it does get caught up in any way that might prevent you from getting quickly to the surface or the stream bank in an emergency.

Here are a few other pointers we have learned about airlines from our experience: Stay aware of where your airline is. Do not allow it to get wrapped and tangled around objects, the suction hose, tangled with other divers’ airlines. Immediately untangle your airline if it does get caught up in any way that might prevent you from getting quickly to the surface or the stream bank in an emergency. And we always replace or repair a damaged or defective airline without delay. Murphy (as in Murphy’s Law) lurks behind every corner! There are so many details to get right in a dredging operation of any size. There are many things which can possibly go wrong. We try to do everything right to avoid problems. But one thing we should never get lazy about is maintenance action on our air systems. If it even looks like it could be a problem, fix it now! And use quality repairs! Clamping copper tubing between two pieces of airline is not the way to do it!

And we always replace or repair a damaged or defective airline without delay. Murphy (as in Murphy’s Law) lurks behind every corner! There are so many details to get right in a dredging operation of any size. There are many things which can possibly go wrong. We try to do everything right to avoid problems. But one thing we should never get lazy about is maintenance action on our air systems. If it even looks like it could be a problem, fix it now! And use quality repairs! Clamping copper tubing between two pieces of airline is not the way to do it! Some have said that the pen is mightier than the sword, and I am sure that on occasions this has truly been the case. Throughout the ages, man has used words to explain, convince and cajole his fellows about one thing or another. Advertising executives are no exception to the rule; and in their deft hands, a word can become downright dangerous or at least costly to some of us. I am, of course, speaking about the use of the language without explaining the meaning of the terms used.

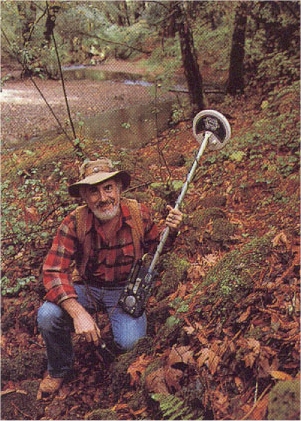

Some have said that the pen is mightier than the sword, and I am sure that on occasions this has truly been the case. Throughout the ages, man has used words to explain, convince and cajole his fellows about one thing or another. Advertising executives are no exception to the rule; and in their deft hands, a word can become downright dangerous or at least costly to some of us. I am, of course, speaking about the use of the language without explaining the meaning of the terms used. But with the advent of meter identification on many detectors, the user was no-longer locked into searching in a discriminate mode with limited depth. He or she could finally search in an all-metal mode if desired and check the meter for probability of target identification. This is where the definition of terms is becoming important and what I have been leading up to. I have recently heard it said that this or that detector is better for prospecting because it doesn’t discriminate, and many a treasure hunter has set aside his or her perfectly good multipurpose unit and bought another unit just for prospecting. I am not suggesting that these new units are not worthy of the task; but in many instances, it was costly and unnecessary to buy two units. First of all, the original unit should be able to cancel the ground effectively; and secondly, the owner must learn the skills necessary to operate it in a prospecting environment. Every company makes such units, and all are capable of finding the elusive gold nugget. The meter should work independently of the all-metal audio signal. That is, you should be able to operate the detector in the all-metal mode and hear every target that the loop passes over. The meter should respond to these targets in some sort of predictable fashion.

But with the advent of meter identification on many detectors, the user was no-longer locked into searching in a discriminate mode with limited depth. He or she could finally search in an all-metal mode if desired and check the meter for probability of target identification. This is where the definition of terms is becoming important and what I have been leading up to. I have recently heard it said that this or that detector is better for prospecting because it doesn’t discriminate, and many a treasure hunter has set aside his or her perfectly good multipurpose unit and bought another unit just for prospecting. I am not suggesting that these new units are not worthy of the task; but in many instances, it was costly and unnecessary to buy two units. First of all, the original unit should be able to cancel the ground effectively; and secondly, the owner must learn the skills necessary to operate it in a prospecting environment. Every company makes such units, and all are capable of finding the elusive gold nugget. The meter should work independently of the all-metal audio signal. That is, you should be able to operate the detector in the all-metal mode and hear every target that the loop passes over. The meter should respond to these targets in some sort of predictable fashion.