By Dave McCracken

“When to do a clean-up”

Some miners like to “clean-up” their sluice boxes after every hour of operation. Some prefer to do clean-up at the end of the day. Others will go for days at a time before cleaning up. This is all a matter of preference and seldom has much to do with the actual needs of the sluice box.

Some miners like to “clean-up” their sluice boxes after every hour of operation. Some prefer to do clean-up at the end of the day. Others will go for days at a time before cleaning up. This is all a matter of preference and seldom has much to do with the actual needs of the sluice box.

More commonly these days, a dredger only cleans-up the “high-grade” section of riffles in his or her dredge after each sample or at the end of a production day. That is a special small section of riffles which catch most of the gold near the head of the sluice. The full recovery system is usually only cleaned-up when enough gold has accumulated to make the effort worthwhile, or it is time to take the dredge out of the water.

There is a method of determining when a sluice box needs to be cleaned up, so that you can keep it operating at its utmost efficiency. If the majority of gold is catching in the upper-third section of the sluice box, then the recovery system is working well.

There is a method of determining when a sluice box needs to be cleaned up, so that you can keep it operating at its utmost efficiency. If the majority of gold is catching in the upper-third section of the sluice box, then the recovery system is working well.

After a sluice box has been run for an extended period of time without being cleaned, the riffles will be substantially concentrated with heavy materials behind them. Sometimes an abundance of heavily-concentrated material in a sluice box can reduce the efficiency of the riffles. This is not always the case. Much depends upon the type of riffles being used and how they are set up in the box. The true test of when a set of riffles is losing its efficiency because of being loaded down with heavy concentrates is when an important amount of gold starts being trapped further down the length of the box than where it normally catches. When this occurs, it is definitely time to clean up your box. Otherwise, clean the box when you like.

Expanded-metal riffles, being short, will tend to load up with heavy black sands faster than the larger types of riffles. Still, a large, visible amount of black sand being present is not necessarily a sign that you are losing gold. Gold is about four times heavier than black sand. As long as there remains fluid action behind the riffles, the black sand might have little or no effect upon gold recovery. The best way to evaluate your recovery system is by direct observation of where the gold is being trapped.

DUMPING OFF

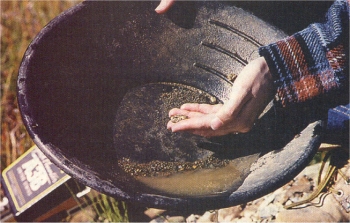

The concentrates which have accumulated in a sluice box can be removed by unsnapping the riffles, carefully removing the carpet underlay, and washing everything into a washtub or bucket. The contents can easily be rinsed out of the carpet underlay inside the washtub.

A medium-wide plastic putty knife can be very helpful in removing lingering concentrates from the high-grade section of a sluice box when that is the only place in the recovery system being cleaned-up.

The concentrates can then be screened into another wash-tub or into a bucket, depending upon what type of screens you are using. Classification of the concentrates into several sizes will allow you to process each more efficiently. The size-classifications that you want to use will depend largely upon how you will process the final concentrates. No matter how you process the final material, you almost always want to begin with a ½-inch or ¼-inch screen, just to eliminate all the larger-sized material from your concentrates. The following video segment demonstrates this preliminary screening, reminding you to carefully remove any gold nuggets which stay on top of the screen before discarding the larger-sized material:

There are several types of final clean-up devices on the market which can help you process the final concentrates, including different kinds of wheels, bowls and miniature sluicing systems. They all work pretty well when set up properly. Here is a video sequence demonstrating the use of a gold wheel to facilitate final clean-up:

Each device has its own instructions about the proper classification-size of concentrates for optimum performance. So you will want to buy or make your screens accordingly. The following video sequence demonstrates a second screening through a common sieve about the size of window screen – which is about normal for splitting concentrates into two sizes:

In my own operations, when we accumulate more than just a small amount of concentrates to clean-up, we have had very good results by first running the concentrates through a plastic Le Trap Sluice. First, though, we screen the concentrates through 8-mesh or 12-mesh screen to remove larger material. The following video sequence shows the Le Trap being used to help with a final clean-up:

Or, rather than use a special device (wheel, bowl, etc), you can work your concentrates completely or nearly down to the gold with the use of a gold pan. In this case, I would suggest that you first classify the material through 8-mesh (8 openings per linear inch) and then through 20 mesh (20 openings per linear inch) screens to break it up into three sizes: 1) the material which stays on top of the 8-mesh screen; 2) the material which passes through the 8-mesh screen but stays on top of the 20-mesh screen; 3) and the material which passes through the 20-mesh screen.

Under normal circumstances, the larger two classifications of concentrate will pan down to gold by themselves quite fast. Because of this, even a final clean-up device is usually only used in the field on that material which will pass through the smallest classification screen.

I have thoroughly demonstrated the panning process in a separate article, so I won’t repeat that here.

FINAL DRY SEPARATION

These final clean-up steps can be done at camp, preferably in a dry environment, where the wind is not blowing much and where there is a table top or some other flat surface available to you for a work space.

Important: Before you do the first step of this process, it is best to work your concentrates down as far as possible, to remove all of the black sands that you possibly can. The more black sand you can remove while the material is wet, the less you have to deal with after it is dried. Sometimes you can remove more black sand with the careful use of a finishing pan (small steel gold pan about 6-inches in diameter) inside of a small wash tub.

Important: Before you do the first step of this process, it is best to work your concentrates down as far as possible, to remove all of the black sands that you possibly can. The more black sand you can remove while the material is wet, the less you have to deal with after it is dried. Sometimes you can remove more black sand with the careful use of a finishing pan (small steel gold pan about 6-inches in diameter) inside of a small wash tub.

A Gold Extractor will allow you to work all of your gold down with no loss, and only about a tablespoon of black sands remaining.

Important Note: The best finishing device I have ever seen for working concentrates down to only about a tablespoon of remaining black sand, with zero loss of your gold, is called a “Gold Extractor.” Once your final concentrates are worked down to a very small amount of black sand remaining, you are ready to go on to the next step.

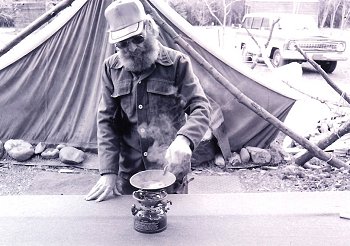

STEP 1: First dry out your final concentrates. This can be accomplished by pouring them into a small metal pan (finishing pan is best) and slowly heating them over an open fire or gas stove-whichever is at hand.

STEP 1: First dry out your final concentrates. This can be accomplished by pouring them into a small metal pan (finishing pan is best) and slowly heating them over an open fire or gas stove-whichever is at hand.

Dry out the concentrates.

CAUTION: Heating the concentrates from a gold mining program should not be done inside of a closed environment. Heating should be done outside and/or in a well-ventilated location, where any and all vapors given off by the various steps will be swept away from you and other bystanders.

You do not want to heat the concentrates too much at this stage. This is because they may still contain some lead. Excessive heat can melt the lead onto some of the gold within the concentrates. Pay attention to heat just enough to thoroughly dry out your concentrates. Be careful that boiling or bubbling during heating is not allowed to spatter gold out of the pan. The following video segment demonstrates this step:

STEP 2: Once the concentrates have cooled enough that they can be handled, they should be screened through a piece of window screen (about 12-mesh). A small piece of window screen, about 6-inches square, is handy to use for this purpose.

STEP 2: Once the concentrates have cooled enough that they can be handled, they should be screened through a piece of window screen (about 12-mesh). A small piece of window screen, about 6-inches square, is handy to use for this purpose.

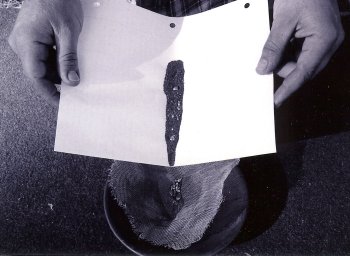

STEP 3: Take the larger-sized concentrates (the material which would not pass through the window screen), and pour them onto a clean piece of paper. If there is a lot of this sized concentrate, this step will have to be done in stages, handling a little at a time. Once the concentrates are poured onto the paper, it is easy to separate the pieces of gold from the impurities. The impurities should be swept off the paper and the gold should be poured into a gold sample bottle. This is where a funnel comes in handy.

STEP 4: Once the larger-sized concentrates have been separated, the remaining concentrates can be classified through a finer-mesh screen. A stainless steel, fine tea strainer (about 20-mesh) works well for this. Tea strainers can be found in just about any grocery store.

STEP 5: Take the larger classification of concentrates from the second screening, pour them onto a clean sheet of paper, and separate the gold from the impurities in the same way that it was done with the larger material in Step 3 above.

Use of a magnet on each size-classification of concentrates can be very helpful to remove those impurities which are magnetic.

Some prefer to use a fine painter’s brush to separate out the non-magnetic impurities. Separation can also be accomplished by using your fingers. This step goes faster if you only do small amounts of concentrate at a time. Pour the gold recovered in this step into the gold sample bottle.

STEP 6: Take the fine concentrates which passed through the final screening and spread them out over a clean sheet of paper. Use a magnet to separate the magnetic black sands from these final concentrates. The magnetic black sands should be dropped onto another sheet of clean paper, spread out, and then gone through with the magnet at least one more time. The reason for this is that some gold can be carried off with the magnetic black sands. They tend to clump together. Once the magnetic black sands have been thoroughly separated from the gold to your satisfaction, pour them into your black sand collection. There may still be some small gold values left with them which can be recovered by other methods at another time.

NOTE: There is a really nice set of final clean-up screens on the market that are made just for the purpose of separating your final concentrates into the ideal size-fractions for final dry separation. I highly recommend them, because they separate your final material into multiple size classifications which make the final dry process go even faster.

STEP 7: Now, all that should be left is your fine gold, possibly some platinum, and a small amount of non-magnetic black sand. These final black sands can be separated by blowing lightly over them while vibrating the sheet of paper. Since the sand is about 4 times lighter than the gold, it will blow off the paper a little at a time, leaving the gold behind. Once all the black sands are gone, you can pick out the pieces of platinum if present, and separate them from the gold. Pour the gold into the same gold sample jar used in the earlier steps.

This dry process (Steps 1-7) goes very quickly if an effort was made during the final wet stages to get as much black sand and other waste material as possible separated from the gold.

CLEANING GOLD

Sometimes placer gold just out of a streambed is very clean and shiny. If this is the case with your gold, after the final dry cleanup procedure is completed, your gold is ready to be weighed and sold or displayed or stored away in a safe place.

Sometimes, gold will come out of a streambed with some impurities attached to it. When this happens, it will be necessary to perform a final cleaning process to make the gold’s natural beauty stand out.

If your gold is not clean and shiny, and you want to get it that way, place it in a small non-breakable water-tight jar about half full of water and add a little dishwashing liquid. It does not seem to matter what kind is used. Fasten the top on the jar and shake the contents vigorously until the gold changes to somewhat of an unnatural glittery color. Sometimes this happens quickly and sometimes it takes a little longer. This mostly depends upon how much gold is in the jar. The more gold, the faster the process. This is because it is the friction of gold against gold which facilitates the cleaning process. Once the gold is glittery, rinse the soapy water out of the jar, pour the gold into a small (metal) finishing pan, and heat it up (outside and down wind) until the gold takes on a deep, natural, shiny luster. It is important to make sure that all of the soap has been rinsed away from the gold using clean water before you dry the gold.

Gold has a tendency to turn a dull color after having been stored in an airtight container for an extended period of time. For this reason, some gold miners and dealers store their gold in water-filled jars, and dry it out just before displaying it or making a sale.

If you should happen to store your gold in an airtight container and notice that its color does not seem to be as bright as it once was, wash it with soap and water and re-heat it, as in the above steps. This process will bring back the beautiful color and luster of the gold.

The best time to weigh your gold to get the most accurate measurement is after you have completed all of the final cleanup steps.

SELLING GOLD

There are numerous markets where you can sell your gold. Refineries will pay you for the fineness (purity) of the gold itself and subtract a few percent for refining charges. In this case, you will receive a little less than the actual value of the gold. Refineries usually will not pay for the silver and platinum contained within your placer gold unless you are delivering it in large quantities. Refineries prefer that you bring your gold to them in large amounts. They will often charge less for refining, and sometimes pay just a bit more for the gold, when it is brought to them in larger quantities.

There are numerous markets where you can sell your gold. Refineries will pay you for the fineness (purity) of the gold itself and subtract a few percent for refining charges. In this case, you will receive a little less than the actual value of the gold. Refineries usually will not pay for the silver and platinum contained within your placer gold unless you are delivering it in large quantities. Refineries prefer that you bring your gold to them in large amounts. They will often charge less for refining, and sometimes pay just a bit more for the gold, when it is brought to them in larger quantities.

Flakes of gold and nuggets have jewelry value on a different market. If marketed to the right buyers, flakes and nuggets can usually bring in more than a refinery will pay-or sometimes even much more.

If you are in gold country and ask around, you can nearly always find someone who is buying placer gold from the local miners. These individuals usually pay cash. Unless the fineness of the gold within the area is lower than normal, there is no reason to settle for less than 70% of the market-value of the gold for that day. This means that the gold is weighed and the buyer pays you for the weight of what you deliver. Impurities are never calculated into this type of deal. If you enquire around, you can usually find someone who is willing to pay 75% of weight. Sometimes you can find an 80% straight-out buyer-which is good.

There are also people out there who are ready to gyp you out of your gold if they can get away with it. It is wise to bring your own pocket calculator along when dealing with a new buyer.

If you go to a dealer who starts figuring a certain percentage of the fineness, and his final figures end up lower than a straight out 70% of the bulk weight of your gold as it is, go find another dealer. This is not to say that 70% is the going rate. You can do better if you look around. Although, you should never have to accept less than 70% of the going market price for your gold. If a dealer starts to tell you all sorts of reasons why your gold is not worth what you want for it, go find someone else. There are plenty of gold buyers around who will at least admire your gold. So there is no reason to hang around and listen to someone who is trying to steal it from you.

Local miners will know who pays the most! Or go up on our web forum and ask. Someone there is sure to turn you onto a good deal!

Cleaning your gold well before you take it somewhere to be sold can help a lot.

Sometimes dentists will give you a good price for your gold, and a phone call or two can pay off. Also, some lawyers and businessmen like to invest in gold. Sometimes you can get up to 100% of spot for your fines (fine gold) when dealing with them.

Some jewelers will pay well for your flakes when they have a demand for them. It is not uncommon to get as much as 90% or better when you make such contacts.

The best way to get top dollar for your gold is to do a lot of inquiring, always with the intention to find more and better markets. Then, when you need some cash, you can sell to the buyer who pays the most.

The yawns being given off by my friend permeated the room so heavily that they clearly placed an uncomfortable shadow over the enthusiasm all the rest of us were feeling. We were on one of the most exciting treasure hunting expeditions I have ever been engaged in, and I was thanking my lucky stars just to be part of the expedition. All of the people involved were very good at their jobs and were enthusiastically involved with this project except my friend. He was bored. In fact, he was so caught up in his own personal boredom, that he was certain everyone else, and the whole world, was also seeing the world in the same mundane way. Talk about being on a different wavelength!

The yawns being given off by my friend permeated the room so heavily that they clearly placed an uncomfortable shadow over the enthusiasm all the rest of us were feeling. We were on one of the most exciting treasure hunting expeditions I have ever been engaged in, and I was thanking my lucky stars just to be part of the expedition. All of the people involved were very good at their jobs and were enthusiastically involved with this project except my friend. He was bored. In fact, he was so caught up in his own personal boredom, that he was certain everyone else, and the whole world, was also seeing the world in the same mundane way. Talk about being on a different wavelength! I asked if someone was sick in his family, or if he had financial or other personal problems that were holding him back. He said there was nothing like that holding him back. To him, for as long as he could remember, he was not able to experience real enthusiasm.

I asked if someone was sick in his family, or if he had financial or other personal problems that were holding him back. He said there was nothing like that holding him back. To him, for as long as he could remember, he was not able to experience real enthusiasm. I suggest the impact of life upon us (how we end up being affected by it) is exactly as we choose it to be. If we decide that the way we are going to feel most of the time is due to some (or lack of) outside or hidden influence or the way others have treated us (or not treated us) in the past, naturally, that’s the way it will be for us.

I suggest the impact of life upon us (how we end up being affected by it) is exactly as we choose it to be. If we decide that the way we are going to feel most of the time is due to some (or lack of) outside or hidden influence or the way others have treated us (or not treated us) in the past, naturally, that’s the way it will be for us.

Something we have known for quite some time is that

Something we have known for quite some time is that

Notwithstanding all the excitement and

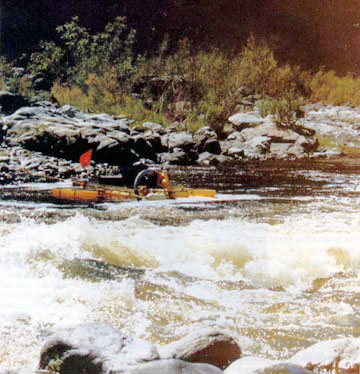

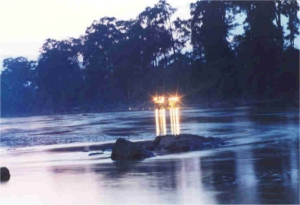

Notwithstanding all the excitement and  In most cases, the “fast water” you are in is not a steady flow of current. It is usually turbulent, varying in direction and intensity. A swirl can hit you from the side and knock you off balance. Or, sometimes it can even hit you from underneath and lift you out of the dredge-hole and into the faster flow. If you get swept down river in fast water, you usually just need to grab hold of the river bottom and work your way over to the slower water, nearer to the stream bank. This movement is normally best-done by continuing to face upstream, into the current, while you point your head and upper-body towards the river-bottom. That posture will nearly always drive you to the bottom where you can get a handhold on rocks or cobbles to anchor yourself down. Then, you can work your way upstream, through the more slack current near the stream bank, and back out to your work-site again. This is all pretty routine in fast-water dredging.

In most cases, the “fast water” you are in is not a steady flow of current. It is usually turbulent, varying in direction and intensity. A swirl can hit you from the side and knock you off balance. Or, sometimes it can even hit you from underneath and lift you out of the dredge-hole and into the faster flow. If you get swept down river in fast water, you usually just need to grab hold of the river bottom and work your way over to the slower water, nearer to the stream bank. This movement is normally best-done by continuing to face upstream, into the current, while you point your head and upper-body towards the river-bottom. That posture will nearly always drive you to the bottom where you can get a handhold on rocks or cobbles to anchor yourself down. Then, you can work your way upstream, through the more slack current near the stream bank, and back out to your work-site again. This is all pretty routine in fast-water dredging. There is not a single a person among us who won’t panic, given the right (wrong) situation. People who say they will never panic under any circumstances are just not facing reality and, obviously, have never come close to drowning. I believe it is better to understand and acknowledge your limitations before you get into trouble. The closer you cut your safety margin on safety issues, the more aware of your limitations you should be. And, the more important it is to plan in advance how you will react to certain types of emergencies. It is already too late to make such plans the moment something bad happens!

There is not a single a person among us who won’t panic, given the right (wrong) situation. People who say they will never panic under any circumstances are just not facing reality and, obviously, have never come close to drowning. I believe it is better to understand and acknowledge your limitations before you get into trouble. The closer you cut your safety margin on safety issues, the more aware of your limitations you should be. And, the more important it is to plan in advance how you will react to certain types of emergencies. It is already too late to make such plans the moment something bad happens! Other types of underwater vulnerabilities are especially present during fast-water dredging activity. Some of this vulnerability is because it is sometimes necessary to weigh yourself down more-heavily with lead weights to stay on the river bottom. Extra weight is needed to give you the necessary stability and leverage to control the suction hose and nozzle and to move rocks and obstacles out of your way. The demands of dredging activity require divers to be so heavily weighted down, that it is impossible to swim at the surface without first discarding the weights that hold you to the bottom.

Other types of underwater vulnerabilities are especially present during fast-water dredging activity. Some of this vulnerability is because it is sometimes necessary to weigh yourself down more-heavily with lead weights to stay on the river bottom. Extra weight is needed to give you the necessary stability and leverage to control the suction hose and nozzle and to move rocks and obstacles out of your way. The demands of dredging activity require divers to be so heavily weighted down, that it is impossible to swim at the surface without first discarding the weights that hold you to the bottom. When working in fast water, all of your normal safety precautions, preventative maintenance measures, and common sense instincts must be scrupulously observed. Fast water may be thought of as a liquid flow of energy that is constantly challenging you and your equipment. Murphy’s Law (“anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”) is always at work in fast water. It is hard enough to deal with the things that you cannot anticipate will happen. You will have enough of these as it is. But, if you neglect to take action with respect to those things that you can reasonably expect to go wrong, you will almost certainly fail in your efforts to dredge in fast water. If it is wrong, fix it now, before it gets worse!

When working in fast water, all of your normal safety precautions, preventative maintenance measures, and common sense instincts must be scrupulously observed. Fast water may be thought of as a liquid flow of energy that is constantly challenging you and your equipment. Murphy’s Law (“anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”) is always at work in fast water. It is hard enough to deal with the things that you cannot anticipate will happen. You will have enough of these as it is. But, if you neglect to take action with respect to those things that you can reasonably expect to go wrong, you will almost certainly fail in your efforts to dredge in fast water. If it is wrong, fix it now, before it gets worse! Otherwise, if we position the dredge directly in the fast water, it will become necessary for the divers to contend with fast water when entering the water from the dredge. This can be done; but it makes the operation more difficult – especially, when the dredgers need to climb back onto the dredge.

Otherwise, if we position the dredge directly in the fast water, it will become necessary for the divers to contend with fast water when entering the water from the dredge. This can be done; but it makes the operation more difficult – especially, when the dredgers need to climb back onto the dredge. Suction hose support booms are standard equipment on the commercial

Suction hose support booms are standard equipment on the commercial  One of the persistent problems of dredging in fast water is the heavy drag on your air line. This can normally be solved by pulling some slack-line into the dredge hole and anchoring it against the current with a single cobble placed on top. This will allow some slack air line between you and the cobble. You want to be sure that your cobble-anchor is not so large that you cannot quickly free your air line in an emergency. Also, when you leave the dredge hole, don’t forget to first disconnect your air line from your anchor.

One of the persistent problems of dredging in fast water is the heavy drag on your air line. This can normally be solved by pulling some slack-line into the dredge hole and anchoring it against the current with a single cobble placed on top. This will allow some slack air line between you and the cobble. You want to be sure that your cobble-anchor is not so large that you cannot quickly free your air line in an emergency. Also, when you leave the dredge hole, don’t forget to first disconnect your air line from your anchor. You should always keep an eye on your diving buddy while dredging in fast water. When we dive with multiple dredgers on an operation, it is standard policy for us all to keep track of each other. If one person needs to leave the dredge-hole or go to the surface for some reason, he always lets someone know he is leaving. Otherwise, when a diver suddenly disappears, we immediately go looking for him. A person in serious trouble underwater only has about 30 seconds to get it together. This is not much time. What good is diving with someone else for the sake of safely, if you are not paying attention to what is happening with him/her, especially in fast water where there is so very little margin for error? A tender, or anyone else resting at the water’s surface, should be paying close attention without distraction when there are dredgers down working in fast water.

You should always keep an eye on your diving buddy while dredging in fast water. When we dive with multiple dredgers on an operation, it is standard policy for us all to keep track of each other. If one person needs to leave the dredge-hole or go to the surface for some reason, he always lets someone know he is leaving. Otherwise, when a diver suddenly disappears, we immediately go looking for him. A person in serious trouble underwater only has about 30 seconds to get it together. This is not much time. What good is diving with someone else for the sake of safely, if you are not paying attention to what is happening with him/her, especially in fast water where there is so very little margin for error? A tender, or anyone else resting at the water’s surface, should be paying close attention without distraction when there are dredgers down working in fast water. What is fast water? It depends upon the individual. An experienced dredger might be much safer in a typhoon of fast, turbulent water, than an inexperienced person would be in slow, shallow water near the bank. The key for each person is to begin learning in a safe and comfortable environment, gain valuable experience over time, and never attempt to do anything that you cannot easily manage, with safety.

What is fast water? It depends upon the individual. An experienced dredger might be much safer in a typhoon of fast, turbulent water, than an inexperienced person would be in slow, shallow water near the bank. The key for each person is to begin learning in a safe and comfortable environment, gain valuable experience over time, and never attempt to do anything that you cannot easily manage, with safety.

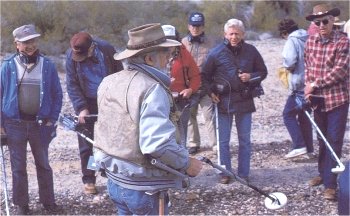

The title of this article can mean different things to different people and thereby add to the mystique surrounding the entire field of metal detecting, for that is what “Electronic Treasure Hunting” is all about. The word electronic should mean the same to everyone. What goes on in that metal box may be a mystery to most of us, but we all know it isn’t magic.

The title of this article can mean different things to different people and thereby add to the mystique surrounding the entire field of metal detecting, for that is what “Electronic Treasure Hunting” is all about. The word electronic should mean the same to everyone. What goes on in that metal box may be a mystery to most of us, but we all know it isn’t magic. I first wanted one when I read about a million-dollar nugget found in Australia by an “

I first wanted one when I read about a million-dollar nugget found in Australia by an “

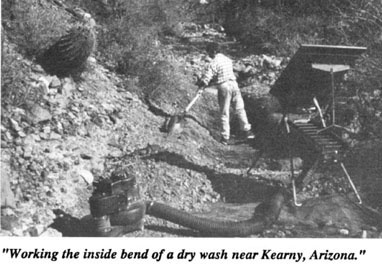

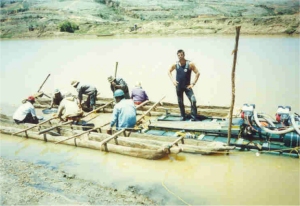

where accessibility is only available by helicopter; it would be wise to first send in a sampling-team to confirm the existence of commercial deposits that will allow you to make a reasonable return on your investment. Knowing that most of the capitalization into this kind of mining project is unlikely to be diverted to some other program at a later time, how much sampling would be enough? It should be enough to:

where accessibility is only available by helicopter; it would be wise to first send in a sampling-team to confirm the existence of commercial deposits that will allow you to make a reasonable return on your investment. Knowing that most of the capitalization into this kind of mining project is unlikely to be diverted to some other program at a later time, how much sampling would be enough? It should be enough to:

4) As mineral deposits can be found at different strata’s within a

4) As mineral deposits can be found at different strata’s within a

9) Ultimately, only the values that can be recovered during production should be included in the final business projections.

9) Ultimately, only the values that can be recovered during production should be included in the final business projections. The second step is to sample the deposit(s) enough to gain a perception of its value. And that’s what this article is really about; how much quantification is necessary? The answer to this question largely depends upon the additional investment that will be required to gear-up for the desired volume of production.

The second step is to sample the deposit(s) enough to gain a perception of its value. And that’s what this article is really about; how much quantification is necessary? The answer to this question largely depends upon the additional investment that will be required to gear-up for the desired volume of production. The reason we can do this, is that under these circumstances, there is no substantial amount of increased financial risk when we transition from sampling into production.

The reason we can do this, is that under these circumstances, there is no substantial amount of increased financial risk when we transition from sampling into production.

4) Doing a series of controlled samples, an equal distance apart, for some distance across an entire section of river, to quantify the average-value of the river gravels. This almost certainly would be accomplished under the guidance of a consulting geologist(s) who will certify the results, in preparation of financial instruments for investment bankers or a public trading company.

4) Doing a series of controlled samples, an equal distance apart, for some distance across an entire section of river, to quantify the average-value of the river gravels. This almost certainly would be accomplished under the guidance of a consulting geologist(s) who will certify the results, in preparation of financial instruments for investment bankers or a public trading company.