This issue is still available! Click here.

By Dave McCracken

The efficiency with which the over-sized material is moved out of the way has a direct impact upon how much gravel and gold will be directed up the suction nozzle!

Dredging technique in gold-bearing streambeds mainly is focused upon removing the over-sized rocks (any rock which is too large to be sucked up the suction nozzle) from the work area of the dredge-hole. In most hard-packed streambeds, this removal of the over-sized material is the bulk of the dredger’s work. From a production standpoint, a large portion of this work has to do with freeing and removing the over-sized rocks from the streambed in an orderly fashion.

Hard-packed streambeds are laid down in horizontal layers during major flood storms. Generally, the streambed is put together like a puzzle, with different rocks locking other rocks into place. Usually, because of gravity, rocks higher up in the streambed (laid down later) are locking lower rocks (laid down earlier) into their position within the streambed.

Because of this, we have found the best means of production is to dredge the hole down a layer at a time. We call this a “top cut.” If you take down a broad horizontal area of the streambed all at once, you uncover a whole strata of rocks which are interconnected like a puzzle. Then, you can see which rocks must be removed first so that you can free the others more easily. This really is the key to production dredging!

Generally, there are two things that drastically slow down the production of less-experienced gold dredgers: (1) plug-ups and (2) “nitpicking.”

The time and energy spent freeing plug-ups from the hose and power-jet cuts directly into how much progress will be made in the dredge-hole.

Plug-ups are caused by rocks jamming in the dredge’s suction hose or power-jet. Everyone gets a few of these. Inexperienced dredgers get many! This comes from not understanding which types of rocks, or combination of rocks, to avoid sucking up the nozzle. Basically, this knowledge comes from hard-won experience in knocking out hundreds or thousands of plug-ups until you reach the point where you become more careful about what goes into the nozzle. I have covered this area quite thoroughly in my “Gold Dredger’s Handbook”

Plug-ups are caused by rocks jamming in the dredge’s suction hose or power-jet. Everyone gets a few of these. Inexperienced dredgers get many! This comes from not understanding which types of rocks, or combination of rocks, to avoid sucking up the nozzle. Basically, this knowledge comes from hard-won experience in knocking out hundreds or thousands of plug-ups until you reach the point where you become more careful about what goes into the nozzle. I have covered this area quite thoroughly in my “Gold Dredger’s Handbook”

During the past several years, some dredge manufacturers have started building dredges using over-sized power-jets. This means that the inside-diameter of the jet-tube is not reduced in size from the inside diameter of the suction hose, helping to greatly reduce the number of plug-ups a dredger will get while in production. Because of this, an oversized jet would be high on my personal priority list if I were in the market for a dredge!

So, the combination of some practice in learning which types of rocks to avoid sucking up the nozzle, and the over-sized power-jet on modern dredges, will eliminate most of the plug-ups that would otherwise hinder production.

The other main loss of production, which we are all guilty of to some extent, comes from a poor production technique which we call “nitpicking”. Nitpicking is when you are trying to free rocks from the streambed which are not yet ready to come out. Nitpicking is dredging around and around rocks which are locked in place by other rocks that need to be freed-up first. Nitpicking is when you are doing things out of the proper order!

When you find yourself making little progress, the key is almost always to widen your dredge-hole.

Production dredging means moving gravel through the nozzle at optimum speed. This is accomplished by making your hole wide enough to allow the over-sized rocks to be easily removed. As soon as you find the rocks are too tight to come apart easily, it is usually time to widen the hole again or take the next top cut. “Top cut” is the term we use to describe when we take a bite off the top-front section of a dredge hole to move the working face forward. “Working face” is the portion of the excavation that we are mining.

An underwater dredging helper can be a big help to remove over-sized material from the dredge-hole. Basically, there are two completely different jobs in an underwater mining operation: (1) nozzle operator (N/O) and (2) rock person (R/P). The nozzle operator is responsible for getting as much material up the nozzle as possible during the production day. Therefore, it is his or her responsibility to direct how the dredge-hole is being taken apart. The rock person has the responsibility to help the nozzle operator by removing those rocks that are immediately in the way of production.

Since there are plenty of oversized rocks that can be removed from a production dredging operation’s work area, it is important that the R/P have some judgment as to which rocks ought to be moved first. Ideally, he will pay attention to what the N/O is doing, and focus his or her efforts primarily on those rocks which are immediately in the nozzle’s way.

The rock person should be moving the very next rock that is in the nozzle’s way.

The rock person should be moving the very next rock that is in the nozzle’s way.

Silt is usually released when a rock is moved out of the streambed. So an R/P must be careful to not “cloud-out” the hole (loss of visibility). This can be avoided by concentrating on (a) moving those rocks that are near to where the N/O is working (this is the first priority), or (b) moving those rocks that have already been freed from the streambed, but not yet removed from the hole.

On occasion, an R/P unwittingly takes over the production operation by randomly moving whatever rocks he or she happens to see. This then causes the N/O to have to follow the R/P around, sucking up the silt which would otherwise cloud-out the dredge hole. This generally results in slowing down production. We have found that it is much better if the R/P accepts the position of being the N/O’s assistant, which allows the latter to direct the progress of the dredge-hole.

The nozzle-operator should communicate with his helpers where he wants to take a cut off the front of the hole.

The nozzle-operator should communicate with his helpers where he wants to take a cut off the front of the hole.

Since production is controlled by how efficiently rocks can be removed from the dredge-hole, it is important to understand that they must also be strategically discarded in a manner which, if possible, will not require them to be moved a second or third time. Generally, this means getting each rock well out of the hole–as far back as necessary. Good judgment is important on this point. You only have so much time and energy available. How far that over-sized rocks will need to be removed from the hole is somewhat dependent upon how deep the excavation is going to go. Early on, we often must guess about this. Sometimes, the streambed turns out to be deeper than we thought it would be. Then, we find ourselves turning around and throwing all the cobbles further back away from the hole. This is not unusual.

We also must use our best judgment to not waste our limited time and energy resources. We really do not want to move all those tons and tons of rocks any further than necessary to allow a safe, orderly progression in the dredge-hole.

As we move our hole forward, and as we dredge layers (“top cuts”) off the front of the hole, we try to leave a taper to prevent rocks from rolling in on top of us. This is an important safety factor. Also, since the N/O’s attention is generally focused on looking for gold, the R/P should be extra vigilant in watching out for safety concerns. Any rocks or boulders that potentially could roll in and injure a team-mate should be removed long  before they have a chance to do so.

before they have a chance to do so.

The rock-person’s attention should always be on safety. If there is danger, he or she should point it out immediately to the Nozzle-operator.

Some rocks will be too large and heavy to throw out of the hole. Therefore, it is good technique to leave a tapered path to the rear of your hole so that boulders can be rolled up and out. If you cannot remove boulders from your hole, the hole may become “bound-up” with over-sized material. This can create a nitpicking situation. It is important to plan your excavation to allow you a certain amount of (safe) working area along the bottom of your dredge hole so you can stay in balance while working.

If you see boulders being uncovered which are too large to roll out of the hole, you should immediately start making room for them on the bedrock at the back of your hole. You normally accomplish this by throwing or rolling other rocks further behind. This takes planning in advance.

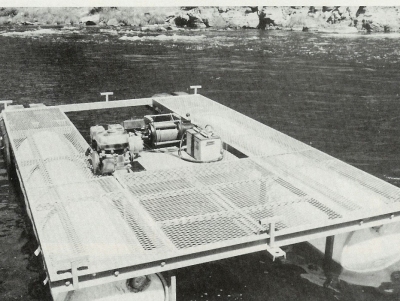

Winch Operator Watching Closely For Diver Signals

Boulder In Sling

Sometimes winching is necessary to remove large boulders or an abundance of large rocks from a dredge-hole. However, because winching takes additional time, the pay-streak usually must contain more gold to justify the time and effort that is required.

The amount of streambed material that you are able to process through a gold dredge will determine the volume of gold that you will recover. Actually, this volume-to-recovery ratio is true of any type of mining operation, whether it is a large-scale lode mine, a small-scale miner using a gold pan, or anything in-between.

The smaller the amount of material that a dredging program has the capacity to process, the richer the pay-dirt must be to recover the same amount of gold. Consequently, a smaller-volume operation often needs to invest more time and energy into sampling to find the more-scarce, higher-grade pay-streaks. For this reason, smaller-volume operations generally spend more time sampling, less time in production; and, therefore, usually recover less gold. But not always!

Having said that, I should also say that successful gold recovery depends upon more than the size of the dredge. A lot has to do with the skill of the operator(s).

As a general rule, gold mining on any scale is volume-sensitive. If you can dredge twice the volume of streambed material, not only can you recover twice the amount of gold, but you may find (many) more lower-grade gold deposits which can be productive when developed. You can also dredge deeper sample holes. This allows you to reach deeper pay-streaks. This is why we always advise beginning gold dredgers to go out and find an easy location where they can practice their basic gold dredge production techniques to improve their speed before they begin a serious sampling program.

It is a good idea to practice your dredging skills, so that you can operate the nozzle efficiently while moving your own oversize material out of the way.

It is a good idea to practice your dredging skills, so that you can operate the nozzle efficiently while moving your own oversize material out of the way.

An inexperienced dredge-miner will sometimes be so slow in volume-production, that he or she may miss valuable pay-streaks simply for lack of being able to process enough gravel, or lack of ability to dredge his or her sample holes large or deep enough during sampling. An inexperienced dredge operator also may not even be aware this is the problem.

When you dredge a sample hole, you must evaluate how much gold you recover against the amount of time and work it took to complete the test hole. If you are only moving at 20% of your potential production speed, you easily can make the mistake of walking away from excellent pay-streaks just because you will believe they are not paying well enough.

When we run larger-sized (8-inch or larger) gold dredges, we almost always have at least two divers working together underwater. The reason for this is because running an eight or ten-inch dredge in six feet or more of streambed material requires that an overwhelming number of over-sized rocks must be moved all the way out of the dredge-hole by hand. This varies from one location to the next. But generally, in hard-packed, natural stream-beds, somewhere between 60 and 75 percent of the material is too large to process through an eight-inch dredge. This is where second and third persons become a big help. A sole-operator in this type of material, when it is deeper than five or six feet, is going to spend a great deal of time throwing rocks out of the hole, rather than operating the suction nozzle.

The smaller the dredge, the shallower the material that a single operator will be able to manage efficiently. Also, some hard-packed streambeds require that most of the over-sized rocks be broken free with the use of a pry bar. This further decreases the amount of nozzle-time on a single-person dredging operation.

In the final analysis, it is the volume of material that is sucked up the nozzle (in any given location) that determines gold production. However, the efficiency with which the over-sized material is moved out of the way has a direct impact upon how much gravel and gold will be directed up the suction nozzle. So, gold production ultimately is controlled by how well the over-sized material (rocks too large to pass into the suction nozzle) is managed. The nozzle-operator’s focus, therefore, should be on directing the nozzle to suck up the gravel that will make it easier to free more over-sized rocks, rather than indiscriminately sucking up any gravel in the hole. In other words, the Nozzle operator should be actively pursuing a plan that keeps the Rock person busy right there where the action is happening!

If a rock person(s) is added to the operation, he or she must increase the program’s efficiency by at least as much as the percentage of gold which he/they is going to receive. This is not difficult to accomplish if conditions are right and the dredging team is organized.

On the other hand, if you are operating a dredge in two or three feet of hard-packed streambed, adding a second person may not increase your production speed enough to make it worthwhile to pay him for his time. This is because the material is shallow, and you may not have to toss the over-sized rocks very far behind in the dredge hole (less effort required to make progress).

When I am operating a production dredge in five or six feet (or more) of streambed material, I can literally bury a rock person with over-sized rocks, and make my helper work like an animal all day long. I also have to work like an animal to accomplish this. The result is a good-paying job for my helper and a substantial increase in my own gold recovery.

When I find myself working in eight or ten feet (or more) of material, I must have at least one or two (or more) rock person(s) to help me. Otherwise, I will be completely buried with cobbles and over-sized rocks all day long and will get in very little nozzle-time.

All of this also applies to smaller-dredge operations. Your ultimate success will be directly proportional to how much material you can get up the nozzle of your dredge in the right locations. The more efficiently you can make that happen, the quicker you will get your nozzle into pay-dirt.

Large-rock management is important! Since most of the material in a natural, hard-packed streambed will be too large to go through the suction nozzle, the progress and speed of your operation will directly depend upon how quickly and efficiently the oversize (cobbles and boulders) materials are moved out of the N/O’s way. Dredging is not just a matter of sucking up some gravel; at least not in the places where most pay-streaks are found.

As shown in the following important video segment, in most pay-streaks, the only gravel that gets sucked up is that which is found between the over-sized rocks. So the key to continued progress depends upon management of over-sized material:

A cutter-head consists of a rotating series of hardened-steel blades that are designed to cut into sand, clay or classified gravel. It does not have the capability to cut through hard-packed streambeds that are made up of over-sized rocks and boulders.This is the reason that cutter-head dredges do not work well in hard-packed streambeds; because they are continuously up against rocks that must be moved out of the way by divers. But it is too dangerous to put divers in a dredge excavation where a cutter-head is operating.

A cutter-head consists of a rotating series of hardened-steel blades that are designed to cut into sand, clay or classified gravel. It does not have the capability to cut through hard-packed streambeds that are made up of over-sized rocks and boulders.This is the reason that cutter-head dredges do not work well in hard-packed streambeds; because they are continuously up against rocks that must be moved out of the way by divers. But it is too dangerous to put divers in a dredge excavation where a cutter-head is operating.

So, there is a lot of good to be said about organizing a system to get the rocks moved out of your way as quickly and efficiently as possible. This is true in dredging on any scale and regardless of whether you are working alone or with a team.

The reason why larger dredges can get more accomplished in gold-bearing streambeds is usually not because they will suck up more gravel. It is because a larger hose and nozzle will suck up a bigger rock. Every rock that can go up the nozzle is a rock that does not need to be packed out of the dredge-hole by hand. This is the primary factor that speeds things up with a larger dredge.

Another major advantage of a two-person team is the substantial amount of emotional support which a second person can add to the operation—especially when you are dredging in deep material, or when you are sampling around for deposits and have not found any in awhile.

On the other hand, the wrong person can inhibit the operation, either physically or emotionally. So, you must be especially careful to select teammates who have work ethics, moral standards and emotional endurances that are similar to your own.

In my own operations, we have found that the key to good teamwork is in establishing standard operating procedures for nearly everything we do. We also work out standard underwater signals. This takes quite a bit of planning and communication in advance, and it is an ever-continuing process. We have standard procedures for removing plug-ups from the hose and jet. We have standard procedures for moving the dredges forward and backward during operation. And, we have standard procedures for every facet of the underwater work — from moving the raw material that is in front of us, to the placement of tailings and cobbles behind our dredge-hole.

As noted above, volume is the key to success—at least to the degree of success. We take this aspect of the work quite seriously in my own operations — to the point where every single moment and every single physical effort is regarded as important to the operational-moment while we are dredging. You will never find the members of my team socializing or goofing-off during the underwater production hours. We allow ourselves to relax during the off-work hours and lunch break. But during production-time, we are entirely focused on the needs of the operation. We treat the dredging-portion of the operation like a competitive team athletic sport. We are not competing against each other. In a team effort, we compete against the barriers that Mother Nature has constructed for us to overcome so that we can recover volume-amounts of gold. To us, our teamwork is kind of like running a relay race. It is rewarding this way when we really synchronize our efforts.

We try to spend a minimum of six hours doing production-dredging or sampling each day. In our operation, this is normally done in two three-hour dives. Other commercial operators prefer three or four shorter dives. I know one commercial dredger in New Zealand who prefers a straight six, seven or eight- hour dive. What an animal!

I like lunch. But, I also agree with the concept of long dives; the reason being that it takes a while to get a good momentum going underwater. Every time you take a break, you need to get that momentum going all over again. What do I mean by “momentum?” Momentum in dredging is very similar to the beat of the drum in driving music. It is the continuous flow of gravel up the nozzle, with the over-sized rocks being moved out of the way in their proper order at just the right moment so that the flow of material into the nozzle is never slowed down. It is everyone doing whatever is necessary to keep that flow happening. It is about synchronizing the right rhythm at optimum speed, and keeping the beat going!

In fact, team-dredging can be kind of like an art form. It is similar to playing music. Only, instead of notes being played on several instruments to form a harmonious melody, the team produces a stream of coordinated effort, using their bodies to move the suction nozzle and the over-sized rocks, in concert, so that all of the effort works together to achieve optimum momentum and harmony.

In his or her initial enthusiasm, an inexperienced R/P may, rather than move the next rock in the path of the N/O, instead, move the wrong rock and cloud-out the dredge-hole with silt. This causes the N/O to be slowed down (1) because of the decreased visibility, and (2) because he or she must now take the time to move the proper rock out of his own way. This is the equivalent of “playing off key,” or playing the wrong musical selection. Everybody else is playing one song, while the new guy is doing something entirely different. The bottom-line for your dredging operation: less volume through the suction nozzle, and less gold at the end of the day.

On the other hand, there is enormous personal and team-satisfaction to operating within a well-structured team-dredging system. Such a system functions best when the N/O is the conductor, and the R/P plays a supporting role, anticipating in advance and taking every possible action to contribute to the N/O’s momentum.

Four-man team on Author’s commercial operation. Notice how everyone is involved up where the action is happening at the suction nozzles.

Four-man team on Author’s commercial operation. Notice how everyone is involved up where the action is happening at the suction nozzles.

This is not just about the next rock which is in the way of the nozzle. It is also about moving the dredge forward a bit as necessary to give the N/O a little more suction hose when it is needed. It is also about the dozen or so other things that are necessary to keep the flow going without a lag.

Volume-momentum is lost every time the N/O has to put the nozzle down to take care of something. That will impact directly upon the success of the operation. Every effort should be made to keep this “down time” to a minimum.

Since volume is really the key, in my own operations, we try to treat dredging pretty-much like a team sport – competitive and physical! When I give my R/P the plug-up signal, he races to the surface to quickly clear the obstruction. He doesn’t just mosey on up there. He moves up there, like running for a touchdown or rounding the bases for the winning home run. This is also the sense of urgency with which he returns to the hole as soon as the plug-up is free. When he sees that rocks are stacking up in the hole, he doubles his pace to catch up. When caught up, he looks around to see where other cobbles might be moved out of the way, without clouding the hole. Or, he might grab the pry bar and start breaking rocks free for the nozzle operator. At the same time, when I am operating the nozzle, I am doing my own job—getting as much material through the nozzle as humanly possible while uncovering new rocks to be moved by the R/P, with the minimum number of plug-ups. And, I do not stop for anything if I can help it. If something else needs to be done, I delegate it to my R/P or other helpers so that I can keep pumping gravel up the nozzle. That’s my job! Everyone’s gold-income depends directly upon how much material is sucked up.

While this statement is also true when you work alone, every effort counts for something in production team dredging. Therefore, everyone needs to pay attention to what is going on in the dredge-hole. R/P’s particularly have to be able to switch gears quickly. At one point, there may be a pile of rocks which needs to be thrown out of the way. The next moment, even before the R/P has moved many of those rocks, he or she may notice something else that is directly impeding the N/O’s progress—like a boulder that needs to be rolled out of the way, or a particularly-difficult cobble which needs to be broken free with the pry bar. The main objective in everyone’s mind should be to support the N/O’s progress. Whatever impedes his progress should be the priority and get immediate attention.

While this statement is also true when you work alone, every effort counts for something in production team dredging. Therefore, everyone needs to pay attention to what is going on in the dredge-hole. R/P’s particularly have to be able to switch gears quickly. At one point, there may be a pile of rocks which needs to be thrown out of the way. The next moment, even before the R/P has moved many of those rocks, he or she may notice something else that is directly impeding the N/O’s progress—like a boulder that needs to be rolled out of the way, or a particularly-difficult cobble which needs to be broken free with the pry bar. The main objective in everyone’s mind should be to support the N/O’s progress. Whatever impedes his progress should be the priority and get immediate attention.

The key to a productive underwater support person is having him or her work to help keeping gravel flowing into the suction nozzle.

The only time I intentionally slow things down is when I am uncovering the gold. I have to keep an eye on that to follow the pay-streak. However, as explained in the following important two video segments, you can also slow down too much by looking. You have to find the proper balance between looking and getting volume up your nozzle:

If the pay-streak is good, I also point out the gold to my helpers as I uncover it. There is emotional gain from this. Everyone deserves the boost. The gold eventually gets spent or hidden away. The memories last your entire lifetime! As demonstrated in the following video sequence, there are few things in life that will give you a bigger emotional boost than finding one of Mother Nature’s rich golden treasures:

As the following video segment demonstrates, once you locate a high-grade pay-streak, it is also very important to invest enough time to locate the downstream and left and right outside boundaries of the deposit. This is to make sure that you are able to develop the whole deposit without burying part of it under tailings or cobbles:

When things get too confused inside the dredge-hole, sometimes the N/O must put down the nozzle and help organize in the hole (move cobbles and boulders out of the hole). But, everyone should be keenly aware of the operational situation that actual production momentum (gravel up the nozzle) has stopped and that it needs to get underway again just as soon as possible.

As noted earlier, and demonstrated in the following video sequence, we take top-cuts off the front of the dredge-hole in production dredging, and we take the material down to the bedrock in layers. We do this because it is the fastest, safest, and most organized method of production dredging:

Sometimes, when conditions are right for it, an R/P may be working right next to the nozzle, breaking the next rock free and quickly throwing it behind in the hole. However, on every top-cut, there comes a time when the N/O decides to drop back and begin a new cut to take off the next layer. The R/P has to pay close attention to this and follow the N/O’s lead. Otherwise, he or she might finish breaking free a rock up in the front of the hole when there is no-longer a nozzle there to suck up the silt. That would be an error.

In other words, the R/P has to keep one eye on what the N/O is doing all the time. Because, if the N/O is a dynamic and energetic person, he or she certainly will not be following the R/P around the dredge-hole. The N/O has to orchestrate the effort. So all of the support-players should be paying close attention and assisting in the N/O’s next move. A good nozzle operator takes apart the hole with an organized method that is easy to follow by the others.

Teamwork also extends up to the dredge-tender on the surface, if you have one. The dredge-tender should continuously monitor the water-volume flowing through the sluice box. If it visibly slows down, he should suspect a plug-up and take steps to locate and clear it. Sometimes, the water-volume has been reduced simply because the N/O has temporarily set the nozzle down over a large rock in the hole. But, on the occasions when there is a plug-up, it is a mark of great teamwork to have a tender handling the problem immediately without having to be told. Volume through the sluice box should also be continuously on the tender’s mind. When gravel stops flowing, he or she should be thinking that something might be wrong.

Teamwork also extends up to the dredge-tender on the surface, if you have one. The dredge-tender should continuously monitor the water-volume flowing through the sluice box. If it visibly slows down, he should suspect a plug-up and take steps to locate and clear it. Sometimes, the water-volume has been reduced simply because the N/O has temporarily set the nozzle down over a large rock in the hole. But, on the occasions when there is a plug-up, it is a mark of great teamwork to have a tender handling the problem immediately without having to be told. Volume through the sluice box should also be continuously on the tender’s mind. When gravel stops flowing, he or she should be thinking that something might be wrong.

When the flow slows down through the recovery system, the tender should just assume there is a plug-up that needs to be freed up from the surface.

That same level of anticipation and teamwork should also apply in other areas, as well. When the tender sees that the dredgers are moving forward in the hole, he should ensure that the dredge is being moved forward accordingly. This is so the N/O will always have a comfortable amount of suction hose to work with. As demonstrated in the following video sequence, different-sized dredges require different lengths of suction hose to allow the nozzle operator a comfortable amount of movement and flexibility:

Good teamwork involves a lot of close observation and timely anticipation to minimize the number of actual orders that need to be given and the consequent amount of down-time. Most of the activity is handled by standard operating procedures which require some planning and communication in advance.

As you might imagine, there are some different opinions about all of this. Some people are simply not running any races. This is fine; but they must understand that they do not have the same gold-recovery potential as others who are working at a faster pace—or, with a more organized system.

Generally, you will not hear anyone on my team complaining—especially when it is time to split-up the gold that we have recovered.

There is not anything difficult to understand about successful gold dredging techniques. The process is quite simple. Serious dredging on any scale is a lot of hard work. Volume is the game! The faster, deeper and more efficiently you can dredge the sample holes, the faster you will find the pay-streaks—and, the better you will make them pay. Even with smaller dredges.

At the times when you are not finding commercial amounts of gold, there is at least the satisfaction of knowing that you are accomplishing optimum performance. And, when you do locate the deposits, the sky is the limit!

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy Gold Prospecting Equipment & Supplies.

- Prospecting for Gold in Hard-packed Streambeds

- Hard Work

- Tuning Into the Wavelength of Success

- More About Sampling

- Schedule of Events

- Books & Videos by this Author

One of our first stops in Baguio was at the Department of Mining & Geology. We were looking for information and maps concerning the historical gold mining areas. Our hope was to find a sizable gold bearing river where local technology has not allowed deeper river

One of our first stops in Baguio was at the Department of Mining & Geology. We were looking for information and maps concerning the historical gold mining areas. Our hope was to find a sizable gold bearing river where local technology has not allowed deeper river

In Legaspi, our guide first took us to the beach, where local miners were recovering small amounts of gold from the beach sands using sluicing devices which were built on stilts to position them above the small waves washing up on the beach. Here follows a video segment that I captured which demonstrates the beach mining activity:

In Legaspi, our guide first took us to the beach, where local miners were recovering small amounts of gold from the beach sands using sluicing devices which were built on stilts to position them above the small waves washing up on the beach. Here follows a video segment that I captured which demonstrates the beach mining activity:

I have to say that these were perhaps the most qualified underwater prospectors I have

I have to say that these were perhaps the most qualified underwater prospectors I have  goodly amounts of gold for their effort, John and I still could

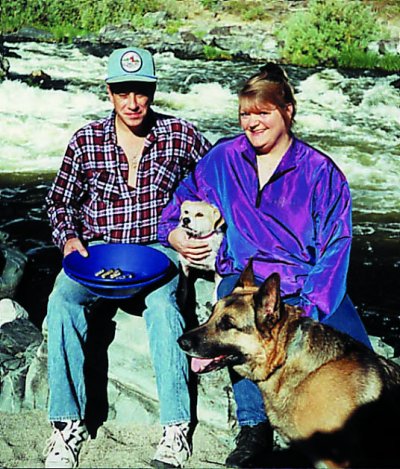

goodly amounts of gold for their effort, John and I still could  It was spring, and John and I were ready for another adventure on the

It was spring, and John and I were ready for another adventure on the  The next day we took our two dogs and climbed down the mountain with the help of a rope tied at the top of the trail.We chose a likely place to start

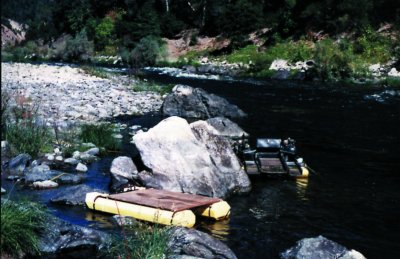

The next day we took our two dogs and climbed down the mountain with the help of a rope tied at the top of the trail.We chose a likely place to start  Then, as the rope burned through my fingers again, John (who was still trying to hold onto it) was dragged over the rocks on his stomach. He saw that the dredge was beginning to sink from the strain we were putting on the rope as it fought against the current, and yelled for me to let it go. What a sick, helpless feeling it was to watch our dredge rushing down the river, out of control!

Then, as the rope burned through my fingers again, John (who was still trying to hold onto it) was dragged over the rocks on his stomach. He saw that the dredge was beginning to sink from the strain we were putting on the rope as it fought against the current, and yelled for me to let it go. What a sick, helpless feeling it was to watch our dredge rushing down the river, out of control! They paddled hard and caught up with it, and pulled it up onto a sand bar on the other side of the river, tying it off on a rock. Thank God for rafters! Without their help, our summer would have been ruined. Our dredge would have surely been smashed up as it went through the next set of rapids, only yards away from where they pulled it out. We decided we’d had enough excitement for the day and went back to our tent camp.

They paddled hard and caught up with it, and pulled it up onto a sand bar on the other side of the river, tying it off on a rock. Thank God for rafters! Without their help, our summer would have been ruined. Our dredge would have surely been smashed up as it went through the next set of rapids, only yards away from where they pulled it out. We decided we’d had enough excitement for the day and went back to our tent camp. We spent our downtime doing some sightseeing. But after being out of the water for a little more than a month, John was dying to get back to dredging. Every little bump and jar caused him a lot of pain, but he managed to work the nozzle. We finished off the spot we were in, getting good gold right to the finish. That took about a week. But under better circumstances, it might only have taken a day or so. We then moved forward between the next set of boulders. The amount of gold we were finding dropped drastically, and we decided we probably should have dropped further back on the river, instead. The strange currents in this area probably dropped the gold differently from normal.

We spent our downtime doing some sightseeing. But after being out of the water for a little more than a month, John was dying to get back to dredging. Every little bump and jar caused him a lot of pain, but he managed to work the nozzle. We finished off the spot we were in, getting good gold right to the finish. That took about a week. But under better circumstances, it might only have taken a day or so. We then moved forward between the next set of boulders. The amount of gold we were finding dropped drastically, and we decided we probably should have dropped further back on the river, instead. The strange currents in this area probably dropped the gold differently from normal. Things were going good and looking better. Yesterday had been a long day, but not as long as I was able to work; about three and a half tanks of gasoline or seven hours. Today, as planned after the gold weigh-up last night, I was at the river early, determined to put in at least a four-tank day . . . and pull my first half-ounce of gold in a day!

Things were going good and looking better. Yesterday had been a long day, but not as long as I was able to work; about three and a half tanks of gasoline or seven hours. Today, as planned after the gold weigh-up last night, I was at the river early, determined to put in at least a four-tank day . . . and pull my first half-ounce of gold in a day!

A partner and I were

A partner and I were

Author’s note: This story is dedicated to Alan Norton (“Alley”), the lead underwater mining specialist who participated in this project. Under near-impossible conditions, Alan made half of the key dives which enabled us to make this a very successful venture.

Author’s note: This story is dedicated to Alan Norton (“Alley”), the lead underwater mining specialist who participated in this project. Under near-impossible conditions, Alan made half of the key dives which enabled us to make this a very successful venture. The dual engine aircraft was

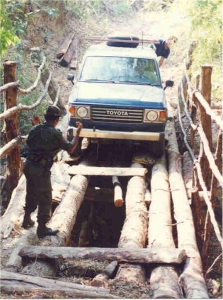

The dual engine aircraft was  It took about an hour to pack the airplane completely full of mining equipment. Since we had to remove the seats to make room for gear, Alley and I were directed to lay up on top of the gear that was stacked up in the belly of the plane. No seat belts! And the plane was loaded so heavily, even the pilot was not sure whether or not we were going to make it off the runway when we took off. We barely made it, and the plane was very sluggish to fly for the remainder of that trip.

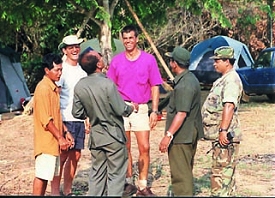

It took about an hour to pack the airplane completely full of mining equipment. Since we had to remove the seats to make room for gear, Alley and I were directed to lay up on top of the gear that was stacked up in the belly of the plane. No seat belts! And the plane was loaded so heavily, even the pilot was not sure whether or not we were going to make it off the runway when we took off. We barely made it, and the plane was very sluggish to fly for the remainder of that trip. After quite some time, at a point when the clouds cleared away just long enough to see, Sam pointed down to a short runway cut out of the jungle. At first, we could not believe we truly were going to try and land there. Sure enough, it was the base camp for the concession. We made one low pass over it. The base camp looked large and well equipped. There was also a small local village right near the base camp. The landing strip was filled with puddles and looked to be mostly mud. Alley and I were a little nervous after Sam’s big buildup, and we had very good reason to be nervous.

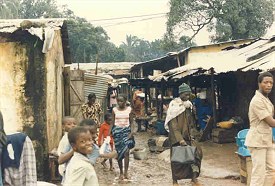

After quite some time, at a point when the clouds cleared away just long enough to see, Sam pointed down to a short runway cut out of the jungle. At first, we could not believe we truly were going to try and land there. Sure enough, it was the base camp for the concession. We made one low pass over it. The base camp looked large and well equipped. There was also a small local village right near the base camp. The landing strip was filled with puddles and looked to be mostly mud. Alley and I were a little nervous after Sam’s big buildup, and we had very good reason to be nervous. Local villagers came out to help us unload the plane. They all seemed like very nice people. After having a chance to load our gear into the bungalow, Sam gave us a short tour of the base camp. The whole area was fenced in. There were numerous screened-in bungalows for the various crew member sleeping quarters, a large kitchen, an office, and a large screened-in workshop area. The company had spent a lot of money getting it all set up. There was a jeep and two off-road motorcycles—all in a poor state of repair. They operated, but without any brakes.

Local villagers came out to help us unload the plane. They all seemed like very nice people. After having a chance to load our gear into the bungalow, Sam gave us a short tour of the base camp. The whole area was fenced in. There were numerous screened-in bungalows for the various crew member sleeping quarters, a large kitchen, an office, and a large screened-in workshop area. The company had spent a lot of money getting it all set up. There was a jeep and two off-road motorcycles—all in a poor state of repair. They operated, but without any brakes. We met the chief, who looked totally wasted on something–probably the Cochili drink. And immediately upon our arrival, the chief ordered some children to bring glasses and drink for everyone. Promptly, our glasses were filled to the rims. Sam quickly downed his first glass, licked his lips, smiled and said, “This is all in the name of good local public relations!” To be polite, I downed half my glass and did my best to choke back my gag. The stuff tasted terrible! I realized my mistake right away when one of the kids immediately took my glass and refilled it to the brim. Alley was paying close attention and slowly sipped his drink, and I followed suit. There was no place to spit if out without being seen, so we had to drink it down. Sam put down three or four more glasses and shortly was slurring his Spanish in final negotiations with the chief. I’m not really sure they understood each other concerning any of the details, but everyone seemed happy with the negotiation.

We met the chief, who looked totally wasted on something–probably the Cochili drink. And immediately upon our arrival, the chief ordered some children to bring glasses and drink for everyone. Promptly, our glasses were filled to the rims. Sam quickly downed his first glass, licked his lips, smiled and said, “This is all in the name of good local public relations!” To be polite, I downed half my glass and did my best to choke back my gag. The stuff tasted terrible! I realized my mistake right away when one of the kids immediately took my glass and refilled it to the brim. Alley was paying close attention and slowly sipped his drink, and I followed suit. There was no place to spit if out without being seen, so we had to drink it down. Sam put down three or four more glasses and shortly was slurring his Spanish in final negotiations with the chief. I’m not really sure they understood each other concerning any of the details, but everyone seemed happy with the negotiation. One very interesting thing about this jungle is that huge trees, for no apparent reason at all, come crashing down. At least several times a day, we would hear huge trees crashing down in a deafening roar. On one occasion, Alan and I were returning to base camp on the jeep trail. We had just come up that trail fifteen minutes before. As we were going down a muddy hill and rounding a bend, we ran smack right into a huge tree which had just fallen across the trail. Good thing I was driving! We smashed into the tree with both of us flying off the bike. Luckily, neither of us were hurt more than just a few bumps and bruises, although the front-end of the motorcycle was damaged. Chalk up one more for the jungle.

One very interesting thing about this jungle is that huge trees, for no apparent reason at all, come crashing down. At least several times a day, we would hear huge trees crashing down in a deafening roar. On one occasion, Alan and I were returning to base camp on the jeep trail. We had just come up that trail fifteen minutes before. As we were going down a muddy hill and rounding a bend, we ran smack right into a huge tree which had just fallen across the trail. Good thing I was driving! We smashed into the tree with both of us flying off the bike. Luckily, neither of us were hurt more than just a few bumps and bruises, although the front-end of the motorcycle was damaged. Chalk up one more for the jungle. We had a three hundred-foot roll of half-inch nylon rope with us for the mining operation. The following day, Alley and I allocated one hundred and fifty feet of that rope to be used to tie our cots up into the shelter beams to keep us well away from the ground. Our Indian guides were quite amused by this. The rest of the rope was used in the dredging operation.

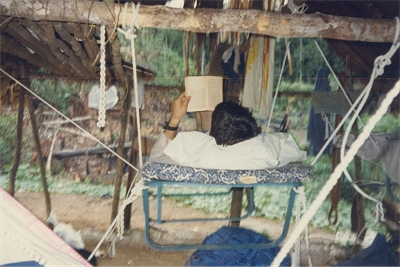

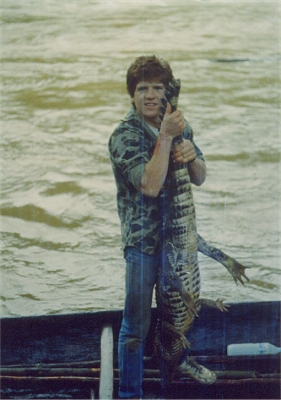

We had a three hundred-foot roll of half-inch nylon rope with us for the mining operation. The following day, Alley and I allocated one hundred and fifty feet of that rope to be used to tie our cots up into the shelter beams to keep us well away from the ground. Our Indian guides were quite amused by this. The rest of the rope was used in the dredging operation. On top of that, the natives caught a hundred-pound Cayman (alligator) with a net out of one of our dredge holes where they had been fishing. It was certainly big enough to take a man’s arm off. At that point, the natives told us these animals came much larger on the river.

On top of that, the natives caught a hundred-pound Cayman (alligator) with a net out of one of our dredge holes where they had been fishing. It was certainly big enough to take a man’s arm off. At that point, the natives told us these animals came much larger on the river. The diving was extremely dangerous. Each time one of us went down, we did so knowing there was a definite possibility that we would not live through it. The only other option was to

The diving was extremely dangerous. Each time one of us went down, we did so knowing there was a definite possibility that we would not live through it. The only other option was to  Our main native guide was named Emilio. He was a real jungle man in every sense of the word. He walked with a limp because of an earlier airplane crash in which he was the sole survivor. His family hut had been hit by lightning several years before, and everyone in the hut was killed except Emilio. He was a real survivor! One night, he went hunting with our shotgun–which was only loaded with a single round of light bird shot. In the darkness of the jungle at three o’clock in the morning, Emilio snuck right up on a five-hundred pound female wild boar and shot it dead–right in the head. We had good meat for several days, and even the disgruntled cook cooperated with some excellent meals.

Our main native guide was named Emilio. He was a real jungle man in every sense of the word. He walked with a limp because of an earlier airplane crash in which he was the sole survivor. His family hut had been hit by lightning several years before, and everyone in the hut was killed except Emilio. He was a real survivor! One night, he went hunting with our shotgun–which was only loaded with a single round of light bird shot. In the darkness of the jungle at three o’clock in the morning, Emilio snuck right up on a five-hundred pound female wild boar and shot it dead–right in the head. We had good meat for several days, and even the disgruntled cook cooperated with some excellent meals.

canoes over top of submerged logs and through rapids. A lot of the time the boats were loaded so heavily that there was only about a half-inch of freeboard on each side. Yet, we never swamped a boat.

canoes over top of submerged logs and through rapids. A lot of the time the boats were loaded so heavily that there was only about a half-inch of freeboard on each side. Yet, we never swamped a boat. While we were hauling our gear along the mile and a half-long trail to the landing strip, I was swarmed by African killer bees. It was terrifying! I heard them coming from quite some distance away. It sounded like a bus coming through the jungle. First, there were only a few bees around me, then a whole bunch. In panic, I was running down the trail at full speed like a mad man out of control, swinging my hat about. Then they were gone. I put my hat back on only to get stung right on top of the head. I felt completely spent. It was time to go home.

While we were hauling our gear along the mile and a half-long trail to the landing strip, I was swarmed by African killer bees. It was terrifying! I heard them coming from quite some distance away. It sounded like a bus coming through the jungle. First, there were only a few bees around me, then a whole bunch. In panic, I was running down the trail at full speed like a mad man out of control, swinging my hat about. Then they were gone. I put my hat back on only to get stung right on top of the head. I felt completely spent. It was time to go home.

It was difficult to see into the deep canyon, because it dropped off so steeply, and because the driver was veering around the bends in the road so fast, racing the Toyota Land Cruiser down the mountain road. This road had no guard rails to prevent us from plunging a thousand feet into the abyss. So, while I would like to have taken a better look at the breath-taking scenery, and I should have captured this part of the adventure with my video camera, all of my personal attention was riveted on the bumpy, narrow, winding road in front of us. I was scared that we were going to fly out over the edge to a certain and violent end! Once in a while, though, I did get a glimpse of a large river cascading down a steady series of natural falls. What an wonderfully-spectacular place! And I did manage to capture the incredible, wild river in the following video segment at one place where we stopped for a moment so I could relieve myself:

It was difficult to see into the deep canyon, because it dropped off so steeply, and because the driver was veering around the bends in the road so fast, racing the Toyota Land Cruiser down the mountain road. This road had no guard rails to prevent us from plunging a thousand feet into the abyss. So, while I would like to have taken a better look at the breath-taking scenery, and I should have captured this part of the adventure with my video camera, all of my personal attention was riveted on the bumpy, narrow, winding road in front of us. I was scared that we were going to fly out over the edge to a certain and violent end! Once in a while, though, I did get a glimpse of a large river cascading down a steady series of natural falls. What an wonderfully-spectacular place! And I did manage to capture the incredible, wild river in the following video segment at one place where we stopped for a moment so I could relieve myself: I was holding on for dear life!

I was holding on for dear life! This was my fourth expedition to Madagascar in search of gold. Madagascar is the world’s fourth largest island. It is located about 400 miles off the south-east coast of mainland Africa. The country is approximately 1,200 miles long by 400 miles wide (at its longest and widest points). So it is no small country. The country is extremely poor, one of the poorest nations on earth. It is also extremely rich in mineral wealth. Especially in

This was my fourth expedition to Madagascar in search of gold. Madagascar is the world’s fourth largest island. It is located about 400 miles off the south-east coast of mainland Africa. The country is approximately 1,200 miles long by 400 miles wide (at its longest and widest points). So it is no small country. The country is extremely poor, one of the poorest nations on earth. It is also extremely rich in mineral wealth. Especially in  This

This  As this area was accessible by road, the

As this area was accessible by road, the

Ernie and his team capturing a little video…

Ernie and his team capturing a little video…

The following video segment shows the gold we recovered from this sample, and captures my summation of what we needed to do to complete our preliminary sampling program on this part of the river:

The following video segment shows the gold we recovered from this sample, and captures my summation of what we needed to do to complete our preliminary sampling program on this part of the river:

I’ll never forget Ernie’s first deep, dirty-water dredging dive. I could see that he was pretty nervous about taking the dive, so I offered to walk (crawl) him out into the river for the first time. He agreed to this. After everything was up and running, I took Ernie by the hand and crawled alongside of him in total darkness out to the middle of the river. It was a

I’ll never forget Ernie’s first deep, dirty-water dredging dive. I could see that he was pretty nervous about taking the dive, so I offered to walk (crawl) him out into the river for the first time. He agreed to this. After everything was up and running, I took Ernie by the hand and crawled alongside of him in total darkness out to the middle of the river. It was a

My BH (Big Hubby) and I became interested in

My BH (Big Hubby) and I became interested in

Because every project is different, relative levels of importance will change depending upon local circumstances. To give you some idea about this, I encourage you to read several articles about the challenges we have faced on different types of projects from

Because every project is different, relative levels of importance will change depending upon local circumstances. To give you some idea about this, I encourage you to read several articles about the challenges we have faced on different types of projects from  In other words, you might not want to buy or lease a mineral property until you are certain for yourself that a commercial opportunity exists for you there. And you also probably will not want to invest the resources to prove-out a deposit unless you are certain you can develop a project if something valuable is found. Balancing these two needs is a challenge that must be overcome.

In other words, you might not want to buy or lease a mineral property until you are certain for yourself that a commercial opportunity exists for you there. And you also probably will not want to invest the resources to prove-out a deposit unless you are certain you can develop a project if something valuable is found. Balancing these two needs is a challenge that must be overcome. In some countries, dealing with the officials can be the biggest challenge to your project manager.

In some countries, dealing with the officials can be the biggest challenge to your project manager.

Any mining program will find itself interacting with government officials and people who reside in the area where the activity will take place. The politics involved with these various relationships is important to maintain, and always will depend, in large part, upon good judgment and emotional flexibility by the project manager. This is even more true when local people will be hired to help support the mining project.

Any mining program will find itself interacting with government officials and people who reside in the area where the activity will take place. The politics involved with these various relationships is important to maintain, and always will depend, in large part, upon good judgment and emotional flexibility by the project manager. This is even more true when local people will be hired to help support the mining project.

It takes very specialized people to recover good samples off the bottom of a muddy river.

It takes very specialized people to recover good samples off the bottom of a muddy river.

This is all about how you are going to do the sampling or production-part of the program. This is the mission-plan. What are you going to do? Where? For how long? Exactly how are you going to accomplish it? Who is going to participate? With the use of what gear and supplies?

This is all about how you are going to do the sampling or production-part of the program. This is the mission-plan. What are you going to do? Where? For how long? Exactly how are you going to accomplish it? Who is going to participate? With the use of what gear and supplies? How deep is the water and streambed material? This will affect the type and size of dredge you will need to accomplish the job, how much dredge-power you will need, and how long the suction hose and air lines need to be.

How deep is the water and streambed material? This will affect the type and size of dredge you will need to accomplish the job, how much dredge-power you will need, and how long the suction hose and air lines need to be.

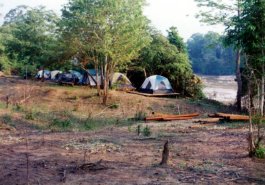

Sometimes, the most important part of shelter is to get off the ground.

Sometimes, the most important part of shelter is to get off the ground. On many of the projects that I have been involved with, we hired several helpers from the local village that were also good at hunting and fishing. This reduced the amount of food that we needed to bring along.

On many of the projects that I have been involved with, we hired several helpers from the local village that were also good at hunting and fishing. This reduced the amount of food that we needed to bring along. It is

It is

Being thoughtful in advance can be far less costly than the loss of key gear or equipment by theft, once you are committed to a sampling program.

Being thoughtful in advance can be far less costly than the loss of key gear or equipment by theft, once you are committed to a sampling program.

This secrecy-concept also extends to the gold you recover on a mining program. Especially during production! We always set up the final processing structure well away from local traffic, and only allow those near that should or must be involved. The product is

This secrecy-concept also extends to the gold you recover on a mining program. Especially during production! We always set up the final processing structure well away from local traffic, and only allow those near that should or must be involved. The product is  A lot depends upon how inaccessible the project site is. When there are villages nearby, you can sometimes find some local medical assistance for matters that are not of a serious nature.

A lot depends upon how inaccessible the project site is. When there are villages nearby, you can sometimes find some local medical assistance for matters that are not of a serious nature.

A) Accidents: While accidents do happen, they mostly can be avoided by planning things out well in advance and having responsible people involved who are being careful. Good management and responsible people can generally stay a few steps ahead of Murphy’s Law (Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong, at the worst possible time!).

A) Accidents: While accidents do happen, they mostly can be avoided by planning things out well in advance and having responsible people involved who are being careful. Good management and responsible people can generally stay a few steps ahead of Murphy’s Law (Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong, at the worst possible time!). Because we dredge in the water during the sampling phase, it is

Because we dredge in the water during the sampling phase, it is

The best way to avoid continuous problems with sanitation (can be very serious), is to set up your own camp some distance away from local communities and bring in your own cook. This can be someone from the same country who lives in an environment where sanitary-measures are a normal way of life. Then, your cook

The best way to avoid continuous problems with sanitation (can be very serious), is to set up your own camp some distance away from local communities and bring in your own cook. This can be someone from the same country who lives in an environment where sanitary-measures are a normal way of life. Then, your cook  An enthusiastic interpreter will dig for the information that you want to obtain. When communicating with local people on the river, sometimes it is necessary to ask many questions in different ways, to different people, to bring them around to the same concepts that you are trying to express. When you work with people from different cultures who have radically-different backgrounds, often you find that they just do not conceptualize things the same way that you do. A good interpreter is able to bridge this gap and help you get the information you want with some degree of accuracy. He will also help you avoid misconceptions or misunderstandings that can build up stress with locals along the river.

An enthusiastic interpreter will dig for the information that you want to obtain. When communicating with local people on the river, sometimes it is necessary to ask many questions in different ways, to different people, to bring them around to the same concepts that you are trying to express. When you work with people from different cultures who have radically-different backgrounds, often you find that they just do not conceptualize things the same way that you do. A good interpreter is able to bridge this gap and help you get the information you want with some degree of accuracy. He will also help you avoid misconceptions or misunderstandings that can build up stress with locals along the river. Longer-range radios are often used between the base camp and civilization. Although atmospheric conditions sometimes make this mode of communication unreliable.

Longer-range radios are often used between the base camp and civilization. Although atmospheric conditions sometimes make this mode of communication unreliable. I saved this section for last, because it is really the most important. If you study all of the material on this web site, you should realize over and over again that it is the personnel on your project that determine the final outcome. They are the key factor that makes it all happen.

I saved this section for last, because it is really the most important. If you study all of the material on this web site, you should realize over and over again that it is the personnel on your project that determine the final outcome. They are the key factor that makes it all happen.