Something we have known for quite some time is that pay-streaks, often very rich pay-streaks, exist in the fast water.

Something we have known for quite some time is that pay-streaks, often very rich pay-streaks, exist in the fast water.

At first, this may seem contradictory to our general understanding that high-grade gold deposits form in areas of the waterway where the water slows down. However, we must keep in mind that pay-streaks are created during major floods. During a major flood, a sudden drop in the bedrock can cause a very good gold trap, like the riffles in a sluice box, but on a very large scale.

If you turn on a garden hose at slow speed, the fast-water area is found directly where the water flows out of the hose. But when you turn the water-pressure up, momentum forces the water farther out. This condition also occurs within the river during a major flood. Areas where the water runs fast during low-water periods are likely to be drop-zones for gold during high water. The heavy momentum/velocity area will be forced farther downstream, leaving a drop-zone for gold just below the bedrock drop. This explains why you can often find pay-streaks under rapids when the river is flowing at low-water levels. It also explains why you seldom find pay-streaks within the first slow-water area below a set of rapids when the river is running at low levels.

Another reason why you are likely to find gold in fast water is because dredging in fast water is more difficult. Therefore, others are less likely to have mined there before you – including the old-timers. For this reason, fast-water areas can often be virgin territory — meaning places where the original streambed material remains in place from thousands of years of natural geologic activity.

What exactly is “fast water?” This depends upon each individual person’s viewpoint. It is primarily a matter of the diver’s comfort level. To some people, if the water is moving at all, it is already too fast to dredge. Other dredgers are able to dredge in water moving so fast that the air bubbles created by the turbulence eliminate all visibility. After diving in really turbulent water, a person’s equilibrium can become so disoriented that he/she can hardly stand up without weaving around, as if intoxicated.

Several years ago, a friend and I were operating a five-inch dredge in some very fast, shallow water. Because of the extreme turbulence, one of us would work the nozzle, while the other would hold onto the dredge to keep it from flipping over. The water was so swift that my friend was swept out of the dredge hole time after time. Once, he was carried away so fast, he didn’t have time to untangle himself from his air line before he reached the end of it. The air line was tangled around his neck! There he was, flopping around in the current, like a flag snapping in a stiff breeze, tethered by the air line around his neck and struggling, unsuccessfully, to regain his footing in three feet of water. After he got safely to the bank, we both laughed so hard that tears were streaming down our faces. That was emotional stress blowing off. Fifteen minutes later, I was the one bouncing in the current behind the dredge, facing backwards at the end of an air line caught between my legs. Needless to say, my friend thought this was pretty funny, too! Dredging in fast water can be fun and exciting (not to mention the gold you can find). But, you must be aware of and prepared for the dangers involved. There is very little margin for error if you get into a situation that is beyond your ability to manage. We all have our limits!

SAFETY

Notwithstanding all the excitement and gold, safety should always be the most important personal consideration. You are the one out there in the field with the responsibility for using good judgment about what you can safely do, without cutting your margin for error too close. The river does not have any sympathy for people who “get in over their heads.” I’ve known several dredgers who lost their lives by over-stepping their personal safety boundaries. It only takes a single mistake. The rest can happen very quickly. Even I have come close to drowning on more than one occasion! All the gold in the world is not worth dying over!

Notwithstanding all the excitement and gold, safety should always be the most important personal consideration. You are the one out there in the field with the responsibility for using good judgment about what you can safely do, without cutting your margin for error too close. The river does not have any sympathy for people who “get in over their heads.” I’ve known several dredgers who lost their lives by over-stepping their personal safety boundaries. It only takes a single mistake. The rest can happen very quickly. Even I have come close to drowning on more than one occasion! All the gold in the world is not worth dying over!

For the sake of safety, it makes good sense for you to not dredge in water that is faster than you are comfortable with. You will have to decide what that is. It is best to practice first in slower water, to gain experience and confidence.

One important thing you should remember about working underwater: Everything may be calm and under control right now; but five seconds later, you can find yourself in the most life-threatening emergency you have ever experienced! This is even true in slow water. But, fast water gives you less margin for safety if you make an error or anything goes wrong. You should not dredge in fast water if you are unable to control the various problem-situations that could develop. You need to anticipate each problem that could possibly arise and work out your response, in advance.

Contrary to what many people believe, being swept down river by the current is not the major concern. This is a normal-happening in fast-water dredging. As long as you have your mask clear and your regulator in your mouth, being swept down river by the current is generally no big deal. That is, of course, unless you are dredging directly above a set of falls or extremely fast water.

In most cases, the “fast water” you are in is not a steady flow of current. It is usually turbulent, varying in direction and intensity. A swirl can hit you from the side and knock you off balance. Or, sometimes it can even hit you from underneath and lift you out of the dredge-hole and into the faster flow. If you get swept down river in fast water, you usually just need to grab hold of the river bottom and work your way over to the slower water, nearer to the stream bank. This movement is normally best-done by continuing to face upstream, into the current, while you point your head and upper-body towards the river-bottom. That posture will nearly always drive you to the bottom where you can get a handhold on rocks or cobbles to anchor yourself down. Then, you can work your way upstream, through the more slack current near the stream bank, and back out to your work-site again. This is all pretty routine in fast-water dredging.

In most cases, the “fast water” you are in is not a steady flow of current. It is usually turbulent, varying in direction and intensity. A swirl can hit you from the side and knock you off balance. Or, sometimes it can even hit you from underneath and lift you out of the dredge-hole and into the faster flow. If you get swept down river in fast water, you usually just need to grab hold of the river bottom and work your way over to the slower water, nearer to the stream bank. This movement is normally best-done by continuing to face upstream, into the current, while you point your head and upper-body towards the river-bottom. That posture will nearly always drive you to the bottom where you can get a handhold on rocks or cobbles to anchor yourself down. Then, you can work your way upstream, through the more slack current near the stream bank, and back out to your work-site again. This is all pretty routine in fast-water dredging.

Getting a hole started is one of the most difficult challenges in fast-water dredging. Once you even get just a small hole started into the surface of the streambed, the suction nozzle in the hole can serve as an anchor to help hold you there against the current. There will also be several cobbles behind you to use as footholds, which also make it easier to hold a position there. After the hole has been expanded to the point where you can get at least part of your body inside, you will find significant relief from the effects of the current’s flow. But, it can sometimes be a real challenge until you do get to that point! At times, you may find it necessary to start your hole in slower water, then gradually work your way out into the faster current.

One of the main concerns when dredging in fast water is having your mask and/or your regulator swept or knocked off your face. This situation is one that can cause a person to panic, especially when both mask (vision) and regulator (air) are lost at the same time.

PANIC

There is not a single a person among us who won’t panic, given the right (wrong) situation. People who say they will never panic under any circumstances are just not facing reality and, obviously, have never come close to drowning. I believe it is better to understand and acknowledge your limitations before you get into trouble. The closer you cut your safety margin on safety issues, the more aware of your limitations you should be. And, the more important it is to plan in advance how you will react to certain types of emergencies. It is already too late to make such plans the moment something bad happens!

There is not a single a person among us who won’t panic, given the right (wrong) situation. People who say they will never panic under any circumstances are just not facing reality and, obviously, have never come close to drowning. I believe it is better to understand and acknowledge your limitations before you get into trouble. The closer you cut your safety margin on safety issues, the more aware of your limitations you should be. And, the more important it is to plan in advance how you will react to certain types of emergencies. It is already too late to make such plans the moment something bad happens!

For me, it takes a lot of personal discipline to stay under control when an unexpected rush of turbulent water jerks my mask off and drags me, blindly and chaotically, down river. This has happened to me on several occasions. I know that under those circumstances, it would not take much more confusion (e.g., air line getting snagged, my body being banged against something, losing my balance, getting a breath full of water from my regulator, etc…) for me to totally lose control and freak out (panic).

I have worked with several guys who have a higher tolerance from panic in the water than I do. And, I know others who feel panicky as soon as they put their heads underwater, even under perfectly-controlled conditions. We are all different, and we each have our own particular point at which we will panic in different circumstances. Everyone has a limit. These limits can actually change from day-to-day, depending upon what other things are happening in our lives. It is better that we not delude ourselves about this. If you allow yourself to get overly-confident, and continually put yourself into situations that can take you beyond your limit, sooner or later you will almost-certainly find yourself tested in a life or death situation.

Panic is a survival-mechanism that takes over when your mind is convinced that your life is in grave danger. At this point, your animal instincts take charge and deprive your intellect of the ability to reason things out. Panic tells you that there is no time left, that you are literally fighting for life just before unconsciousness. The situation demands that you spend your last/maximum physical effort to remove yourself from the danger that is about to mortally injure you or cause you to lose your life. Panic is a horrible, terrifying, and, sometimes, embarrassing experience that happens when your normal, rational self loses control, and the animal-part of you takes over.

There are milder versions of panic. Someone might “panic” and do something silly or foolish in a business or a personal setting. That is not the type of panic that I am talking about here. I’m talking about the raw physical panic that grips you at the moment you realize you may be at the point of losing your life.

There is always a chance of getting into serious trouble any time you are working under the water. Trouble underwater is serious because humans cannot breathe water. There is no margin. You are either breathing air or you are not. It is an immediate emergency when there is no air. Such emergencies can happen in a split second, any time you are in a dredging environment.

TAKING EXTRA PRECAUTIONS

Other types of underwater vulnerabilities are especially present during fast-water dredging activity. Some of this vulnerability is because it is sometimes necessary to weigh yourself down more-heavily with lead weights to stay on the river bottom. Extra weight is needed to give you the necessary stability and leverage to control the suction hose and nozzle and to move rocks and obstacles out of your way. The demands of dredging activity require divers to be so heavily weighted down, that it is impossible to swim at the surface without first discarding the weights that hold you to the bottom.

Other types of underwater vulnerabilities are especially present during fast-water dredging activity. Some of this vulnerability is because it is sometimes necessary to weigh yourself down more-heavily with lead weights to stay on the river bottom. Extra weight is needed to give you the necessary stability and leverage to control the suction hose and nozzle and to move rocks and obstacles out of your way. The demands of dredging activity require divers to be so heavily weighted down, that it is impossible to swim at the surface without first discarding the weights that hold you to the bottom.

One of the most serious dangers to a dredger is the possibility of being pinned to the bottom by a heavy rock or boulder. All of the oversized rocks that cannot be sucked through the dredge nozzle must be moved out of the hole by hand or with the use of winching equipment. When undercutting the streambed, or taking apart the dredge hole, there is the possibility of larger rocks rolling in on top of you. This possibility increases when you are working in turbulent, fast water. The erratic changes in the pressure that the water exerts on the exposed streambed material, inside and around the dredge-hole, can cause boulders to loosen up and roll into the hole. These same boulders, if located in a streambed where the water is running more slowly, might not loosen up the same way, if at all. For this reason, a fast-water dredger must take extra precautions to remove all larger-sized rocks when they are exposed. One of our mottos is: “You have to get the boulders before they have a chance to get you!”

When working in fast water, all of your normal safety precautions, preventative maintenance measures, and common sense instincts must be scrupulously observed. Fast water may be thought of as a liquid flow of energy that is constantly challenging you and your equipment. Murphy’s Law (“anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”) is always at work in fast water. It is hard enough to deal with the things that you cannot anticipate will happen. You will have enough of these as it is. But, if you neglect to take action with respect to those things that you can reasonably expect to go wrong, you will almost certainly fail in your efforts to dredge in fast water. If it is wrong, fix it now, before it gets worse!

When working in fast water, all of your normal safety precautions, preventative maintenance measures, and common sense instincts must be scrupulously observed. Fast water may be thought of as a liquid flow of energy that is constantly challenging you and your equipment. Murphy’s Law (“anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”) is always at work in fast water. It is hard enough to deal with the things that you cannot anticipate will happen. You will have enough of these as it is. But, if you neglect to take action with respect to those things that you can reasonably expect to go wrong, you will almost certainly fail in your efforts to dredge in fast water. If it is wrong, fix it now, before it gets worse!

OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

My dredging partners and I have found that it is physically possible to dredge in water that is too fast for the safety of our dredge — even the kind of dredge that has been designed for fast water. Therefore, the need to operate in an environment that is safe for your dredge is one of the major limiting factors in fast-water dredging.

Most fast-water dredgers add more flotation to their dredge platforms to give more stability. This can be done in different ways, including additional pontoons, inflated tire inner tubes, PVC pipe material, Styrofoam, etc.

One of the main considerations when adding more flotation to a dredge is to avoid increasing the drag against the current. Additional drag causes problems in two ways:

1) The fast-water current puts more strain on your dredge, frame, and tie-off lines.

2) More importantly, the surface-tension caused by all that additional water dragging around the dredge makes it difficult to work near the dredge when you are in the water (which can be a particular problem when you are trying to knock out plug-ups from the suction hose near the dredge).

Another goal when adding flotation is to keep the floats as narrow as possible. A wide set of floats is more likely to be tossed or dragged around by the turbulent flow of fast water.

Generally, when working in fast water, I try to find a location for the dredge where the water is a bit slower, just next to the fast water where I plan to work. This way, I can enter the river in slower water and work my way out underneath the faster water, adding suction hose as necessary.

Otherwise, if we position the dredge directly in the fast water, it will become necessary for the divers to contend with fast water when entering the water from the dredge. This can be done; but it makes the operation more difficult – especially, when the dredgers need to climb back onto the dredge.

Otherwise, if we position the dredge directly in the fast water, it will become necessary for the divers to contend with fast water when entering the water from the dredge. This can be done; but it makes the operation more difficult – especially, when the dredgers need to climb back onto the dredge.

Also, the buildup of cobbles and tailings near the dredge can add to the surface-tension and create an even faster current flow under and around the dredge.

When you are set up with the dredge positioned off to the side in some pocket of slower water, your suction hose will be running perpendicular, at least to some degree, to the flow of the fast water. That much hose exposed broadside to the current creates enormous drag, which can cause the suction hose to kink usually within a foot or so of where it attaches to your power jet. Hose-kinks will cause continuous plug-up problems, so they must be avoided. Therefore, you may find it necessary to disconnect the suction hose and cut off the section that has been kinked. However, you cannot shorten your suction hose very much before you lose the amount of operational flexibility you need for freedom of movement while dredging.

Suction-hose kinks can usually be avoided by setting up a special harness to support the hose in fast water. This is often done by rigging one or two extra ropes down from your main tie-off line. The ropes are fastened to the suction hose at points which will allow the hose to be flexed back by the current, but not to the critical kinking point. You must allow the hose to flex back. It is the bend in the suction hose which allows you the movement to expand the size of your dredge hole.

It is best, when rigging a fast-water harness, to rig it in conjunction with your main dredge tie-off line. This way, the entire dredge and suction-hose harness will move together, as a unit, when you need to move the equipment forward as your dredge-hole progresses.

Suction hose support booms are standard equipment on the commercial Pro-Mack dredges.

Suction hose support booms are standard equipment on the commercial Pro-Mack dredges.

Larger and commercial dredges may be equipped with booms, which can be extended out in front and used to secure a suction-hose safety harness. In this manner, when the dredge moves forward, the suction-hose safety harness moves with it, as in the situation above.

Another concern in fast-water dredging is to keep your suction nozzle and hose from being swept out of your dredge hole. Sometimes, the current will put so much drag on the suction hose that it takes all of your strength and energy to get any nozzle-work done at all! In such a case, you can relieve the main strain of the drag by tying a section of the suction hose to a large rock at the rear of the dredge hole or some other anchor point further upstream. When doing this, always leave enough slack in the hose to allow you to move the suction nozzle forward as your dredge-hole progresses. Also, be sure to remember to untie the suction hose from the river-bottom before you move the dredge. Otherwise, you can damage the hose by causing kinks in the middle! If you kink the hose in the middle, you will have to replace the hose!

We have also worked out a way to extend the suction hose, swing it out on a pendulum line, and anchor it in place using a spare weight belt. This method nearly eliminates all of the hose drag for the person managing the nozzle.

When you take a lunch-break or knock off for the day, you can anchor your hose and nozzle by either piling rocks on the suction nozzle or by tying the nozzle to a large rock in the bottom of the dredge hole. It is not any fun to start a production-dive by having to work against the current to get your suction hose back up into your dredge hole, because the fast water blew it out after your previous dive. But, of course, all fast-water dredgers get many chances to experience this. It is a normal part of the routine!

One important safety point: When using ropes underwater, it is a bad idea to use any more than is absolutely necessary. A lose rope is poison to divers underwater, especially in swift water! Always cut off any excess rope or pile rocks on top to hold it down. If there is a length of loose rope flopping around in the current, something (like your air line) always seems to get tangled in it. Loose rope under water is dangerous!

Your air line can be another source of problems when dredging in fast water. Always be sure to get all the loops out of your air line before starting your dive. Otherwise, the current can pull these loops into kinks, which can immediately cut off your air supply. Not fun!

When you turn around in your dredge hole to roll boulders, toss cobbles, or do any of the many other things associated with production dredging or sampling, get into the habit of exactly reversing your turn when you face forward again (turning back counterclockwise is “cancelled out” by turning forward clockwise). This practice will help prevent you from putting lots of loops in your air line during the course of the dive. Each loop is a potential kink that can cut off your air supply in fast water. Each loop also increases the amount of drag being brought to bear on your air line in fast water.

If you should get a kink in your air line that cuts off your air supply, you can usually get some immediate relief by pulling your air line in toward your body and letting it go. When you let it go, the pressure is temporarily removed from the kink, and you can usually get a single breath of air. I always try this once, quickly, when my own air is suddenly cut off. If that does not give me immediate relief, I crawl right over to the surface so I can properly correct the problem.

If you are experiencing any difficulty with a kinking air line, your best course of action is to immediately remove every single loop in the line. Getting rid of the loops will require you to rotate yourself in circles, going in the appropriate direction, until the air line is straight again.

Several years ago, I was dredging in fast water with a guy who had to repeatedly dive out of our dredge hole because of a kinking air line. After about the fifth time, I suggested that he take the time to straighten out his air line to fix this problem. This remedy only worked for a short time, because he had developed the habit of turning around and around in the dredge hole as he was moving rocks, which just created more and more loops in his line. Fifteen minutes later, he was diving right back out of the dredge hole again.

These days, you can buy a heavier-type of “safety” airline that will prevent kinking in all but the swiftest of fast water. I recommend this heavier air line to anyone who plans to dredge in swift current.

By the way, your air line is also your direct connection to the dredge and to safety. When you connect your air line to the dredge, even in slow water, it should be wrapped around the dredge frame several times before being attached to the air fitting on the dredge. Most air fittings are made of brass. If you should need to use your air line to pull yourself to the dredge in an emergency, it is better that you not have to depend solely upon the strength of a brass fitting!

Nearly all experienced dredgers are aware of the fact that their air lines are an extension of themselves while under water. Especially in fast water, it is very important that you not allow your air line to tangle around parts of the dredge, underwater obstacles, and/or the air lines of other divers in the dredge hole. If you cross over the top of another diver’s air line, keep that in mind, so you will be sure to cross back over it again when you return. Each time you go to the surface, to remove a plug-up or for whatever reason, take a moment to untangle your line from anything it may have wrapped around. As a standard practice, all dredgers should always untangle your air lines each time you return to the surface for any reason. I personally never end a dive without first freeing my airline completely, so it will be ready for the next dive.

One of the persistent problems of dredging in fast water is the heavy drag on your air line. This can normally be solved by pulling some slack-line into the dredge hole and anchoring it against the current with a single cobble placed on top. This will allow some slack air line between you and the cobble. You want to be sure that your cobble-anchor is not so large that you cannot quickly free your air line in an emergency. Also, when you leave the dredge hole, don’t forget to first disconnect your air line from your anchor.

One of the persistent problems of dredging in fast water is the heavy drag on your air line. This can normally be solved by pulling some slack-line into the dredge hole and anchoring it against the current with a single cobble placed on top. This will allow some slack air line between you and the cobble. You want to be sure that your cobble-anchor is not so large that you cannot quickly free your air line in an emergency. Also, when you leave the dredge hole, don’t forget to first disconnect your air line from your anchor.

Full face masks are generally not well-suited for diving in swift water. Since they are larger, with substantially more surface area, they are more likely to get accidentally dislodged from your face. This can happen when the mask is bumped on another diver, or an obstacle, or when turbulent water catches it, especially from the side. To further complicate matters, when a full face mask fills with water, the regulator usually does as well. Having to clear the water out of your mask and regulator at the same time can be more difficult and contribute to a panic situation. I personally find that I am more prone to feeling panicky when something goes wrong inside of a full face mask. If your reactions are similar to mine, you may want to avoid using a full face mask in fast water.

DO’S AND DON’TS!

In any kind of a dredging operation, fast or slow water, it is wise to become familiar with your surroundings as your first priority. Before you begin work, make sure you know the easiest and most direct route to crawl over to the surface in the case of an emergency. Don’t wait until an emergency happens before you think about this. By then, it is too late!

Here is some really good advice: Do not tie yourself into a dredge hole in fast water to keep from being swept down river. It is bad enough having a heavy load of lead attached to your body! If you have to tie something, tie the suction nozzle from a point further up river (with no loose rope flapping in your face). Then hold onto the nozzle to keep yourself steady and in place, while you get the hole started. Get rid of the rope as soon as you have a hole started!

Generally, the most effective way to maintain your position in fast water is to streamline your body properly, with your head and chest close to the river-bottom and your rear-end slightly elevated. This posture allows the water-flow to push you down, toward the bottom, so you can get a better footing. Begin creating your dredge hole as soon as you can. The hole will help anchor you in place. The larger you dredge the hole, the easier it gets.

Some dredgers try to solve their stability problem by putting a lot more lead on their weight belts. Sometimes in turbulent water, more lead can be a help. But, be extra careful when walking out of the water on the slippery bottom, so you don’t overload your ankles and knees and injure yourself.

Most importantly, it is very unwise to solve your fast-water buoyancy/stability problem by adding a bunch of additional weight belts. Take it from me; it is hard enough to get one belt off in a hurry, without compounding the emergency with three of them! Sometimes, you cannot manage the needed extra weight without 2 weight belts, but you must understand that a second belt substantially reduces safety margin in an emergency. Additional belts tend to shift around so that the quick releases are in different places, often behind you where it is more difficult to release them during an emergency. Difficulty in finding them in an emergency can contribute to a panic situation and put your life at risk.

Whatever else you do, early in your dredging career, it is wise to discipline yourself to never try and swim for the surface in an emergency while wearing your heavy weight belt. It just doesn’t work! In a panic situation, your body will want to go immediately for the surface instead of removing the weight belt. I have personally saved two people from drowning who were trying to ”swim for it” with their weight belts on. By the time they realized swimming was not going to work, they were in too much trouble (panic) to get their own belts off!

This does not mean you can’t get a good footing on the bottom and jump up to the surface for one quick breath of air. You can do that in an emergency, as long as the water is not too deep or fast. But, if you cannot crawl over to the surface quickly, your first priority should always be to get the lead weights off as soon as possible.

Keep in mind that you usually cannot see the quick-release buckle on your weight belt while underwater. This is because your face mask blocks your vision at that angle. So, it is important to practice locating the quick-release buckle by feeling for it. It is also very important to keep your belt from shifting around, so that the buckle always remains directly on the front of your body. One of the problems we already noted when wearing more than one belt, is that the top one tends to shift around. There is not much you can do about that. So with two belts, you should be prepared to find the top buckle behind your body!

You may also find that it is better to first remove your work glove before trying to release your buckle in an emergency. When I get in trouble, the first thing I do is get rid of the glove on my right hand!

These are all things you must be able to do quickly and instinctively before venturing into fast water. A wise skydiver would never jump out of an airplane without first receiving enough practice and instruction in how to find his rip cord. Similarly, a dredger’s life should be just as well protected by having a confident ability to release your weight belt quickly in an emergency.

Some of the weight belts on the market also include a suspender harness. The only ones I recommend are the ones that have a quick-release, D-ring on one of the suspenders that allows the shoulder harness to come loose on one side when you release a single waist belt buckle. Otherwise, in an emergency, you may find it too difficult to get out of the suspenders, even if the waist belt is released.

All this advice is coming from a guy that has devoted a large part of my life living on the edge. You can sit there in the comfort of your computer reading this stuff and feel quite certain that you can manage any or all of these things if they should come to pass when you are out dredging. But when the severe emergency happens, you are not the same person. You are a maniac!

You should always keep an eye on your diving buddy while dredging in fast water. When we dive with multiple dredgers on an operation, it is standard policy for us all to keep track of each other. If one person needs to leave the dredge-hole or go to the surface for some reason, he always lets someone know he is leaving. Otherwise, when a diver suddenly disappears, we immediately go looking for him. A person in serious trouble underwater only has about 30 seconds to get it together. This is not much time. What good is diving with someone else for the sake of safely, if you are not paying attention to what is happening with him/her, especially in fast water where there is so very little margin for error? A tender, or anyone else resting at the water’s surface, should be paying close attention without distraction when there are dredgers down working in fast water.

You should always keep an eye on your diving buddy while dredging in fast water. When we dive with multiple dredgers on an operation, it is standard policy for us all to keep track of each other. If one person needs to leave the dredge-hole or go to the surface for some reason, he always lets someone know he is leaving. Otherwise, when a diver suddenly disappears, we immediately go looking for him. A person in serious trouble underwater only has about 30 seconds to get it together. This is not much time. What good is diving with someone else for the sake of safely, if you are not paying attention to what is happening with him/her, especially in fast water where there is so very little margin for error? A tender, or anyone else resting at the water’s surface, should be paying close attention without distraction when there are dredgers down working in fast water.

If all of this has frightened you, that’s good! That means I have accomplished my goal of alerting you to the dangers inherent in fast-water dredging. Being alert to, and fearful of, those dangers is the starting-point for making your own preparations and contingency plans for dealing with them – before you start working in fast water.

What is fast water? It depends upon the individual. An experienced dredger might be much safer in a typhoon of fast, turbulent water, than an inexperienced person would be in slow, shallow water near the bank. The key for each person is to begin learning in a safe and comfortable environment, gain valuable experience over time, and never attempt to do anything that you cannot easily manage, with safety.

What is fast water? It depends upon the individual. An experienced dredger might be much safer in a typhoon of fast, turbulent water, than an inexperienced person would be in slow, shallow water near the bank. The key for each person is to begin learning in a safe and comfortable environment, gain valuable experience over time, and never attempt to do anything that you cannot easily manage, with safety.

This is not only a matter of following through with a single plan. Sometimes, people are unwilling to depart from some course of action once they get started into it. Sampling requires more emotional flexibility than this. Many times, we are just guessing, or hoping, when we begin a sampling operation. Then, as we sink our sample holes, if we are paying attention, we learn more about the area and are able to adjust our sampling plan accordingly. We learn where the gold path (the highway that gold follows in the waterway) is more likely to be by finding out where it isn’t. We find out that the streambed is too deep in some sections of the river by dredging test holes in places where we can’t reach the bottom. We have to be prepared to adjust our sample plan each time we learn something new.

This is not only a matter of following through with a single plan. Sometimes, people are unwilling to depart from some course of action once they get started into it. Sampling requires more emotional flexibility than this. Many times, we are just guessing, or hoping, when we begin a sampling operation. Then, as we sink our sample holes, if we are paying attention, we learn more about the area and are able to adjust our sampling plan accordingly. We learn where the gold path (the highway that gold follows in the waterway) is more likely to be by finding out where it isn’t. We find out that the streambed is too deep in some sections of the river by dredging test holes in places where we can’t reach the bottom. We have to be prepared to adjust our sample plan each time we learn something new. Sampling technology is easy. Gold follows a path in the waterway and deposits at the bottom of hard-packed streambed layers. You find the deposits by first completing sample holes across the waterway to establish where (laterally) the gold path is located, and in what layer (depth) of the streambed it is found. Then, you sample down to the depth of that layer, along that path, until you find the deposit you are looking for. That is the essence of sampling technology, wrapped up in the last three sentences.

Sampling technology is easy. Gold follows a path in the waterway and deposits at the bottom of hard-packed streambed layers. You find the deposits by first completing sample holes across the waterway to establish where (laterally) the gold path is located, and in what layer (depth) of the streambed it is found. Then, you sample down to the depth of that layer, along that path, until you find the deposit you are looking for. That is the essence of sampling technology, wrapped up in the last three sentences. Stop and think about this for a moment: If we already knew where the gold was, we would not have to sample. We could just go into production! But, if it were that easy, someone else would have already taken all the gold. The reason there is so much gold remaining in today’s waterways is because it is not visible. And, since no one can see it, most people believe it is not there.

Stop and think about this for a moment: If we already knew where the gold was, we would not have to sample. We could just go into production! But, if it were that easy, someone else would have already taken all the gold. The reason there is so much gold remaining in today’s waterways is because it is not visible. And, since no one can see it, most people believe it is not there. I often see people get discouraged when they fail to find a rich gold deposit in the first sample hole. We all experience this to some extent. But, this happens only because we have allowed ourselves to set unreasonably-high expectations. The sampling process is never about a single sample hole. Rather, it requires us to spread out across a waterway to find the “gold path,” no matter how many sample holes that may take. That’s the mission. Sometimes it takes 4 or 5 samples. Sometimes it takes more. How can you expect to guess it right on the first try? Isn’t that an unfair and unrealistic expectation?

I often see people get discouraged when they fail to find a rich gold deposit in the first sample hole. We all experience this to some extent. But, this happens only because we have allowed ourselves to set unreasonably-high expectations. The sampling process is never about a single sample hole. Rather, it requires us to spread out across a waterway to find the “gold path,” no matter how many sample holes that may take. That’s the mission. Sometimes it takes 4 or 5 samples. Sometimes it takes more. How can you expect to guess it right on the first try? Isn’t that an unfair and unrealistic expectation? Then, your focus will be where it belongs.

Then, your focus will be where it belongs.

Because every project is different, relative levels of importance will change depending upon local circumstances. To give you some idea about this, I encourage you to read several articles about the challenges we have faced on different types of projects from

Because every project is different, relative levels of importance will change depending upon local circumstances. To give you some idea about this, I encourage you to read several articles about the challenges we have faced on different types of projects from  In other words, you might not want to buy or lease a mineral property until you are certain for yourself that a commercial opportunity exists for you there. And you also probably will not want to invest the resources to prove-out a deposit unless you are certain you can develop a project if something valuable is found. Balancing these two needs is a challenge that must be overcome.

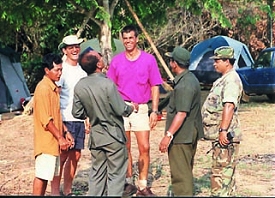

In other words, you might not want to buy or lease a mineral property until you are certain for yourself that a commercial opportunity exists for you there. And you also probably will not want to invest the resources to prove-out a deposit unless you are certain you can develop a project if something valuable is found. Balancing these two needs is a challenge that must be overcome. In some countries, dealing with the officials can be the biggest challenge to your project manager.

In some countries, dealing with the officials can be the biggest challenge to your project manager.

Any mining program will find itself interacting with government officials and people who reside in the area where the activity will take place. The politics involved with these various relationships is important to maintain, and always will depend, in large part, upon good judgment and emotional flexibility by the project manager. This is even more true when local people will be hired to help support the mining project.

Any mining program will find itself interacting with government officials and people who reside in the area where the activity will take place. The politics involved with these various relationships is important to maintain, and always will depend, in large part, upon good judgment and emotional flexibility by the project manager. This is even more true when local people will be hired to help support the mining project.

It takes very specialized people to recover good samples off the bottom of a muddy river.

It takes very specialized people to recover good samples off the bottom of a muddy river.

This is all about how you are going to do the sampling or production-part of the program. This is the mission-plan. What are you going to do? Where? For how long? Exactly how are you going to accomplish it? Who is going to participate? With the use of what gear and supplies?

This is all about how you are going to do the sampling or production-part of the program. This is the mission-plan. What are you going to do? Where? For how long? Exactly how are you going to accomplish it? Who is going to participate? With the use of what gear and supplies? How deep is the water and streambed material? This will affect the type and size of dredge you will need to accomplish the job, how much dredge-power you will need, and how long the suction hose and air lines need to be.

How deep is the water and streambed material? This will affect the type and size of dredge you will need to accomplish the job, how much dredge-power you will need, and how long the suction hose and air lines need to be.

Sometimes, the most important part of shelter is to get off the ground.

Sometimes, the most important part of shelter is to get off the ground. On many of the projects that I have been involved with, we hired several helpers from the local village that were also good at hunting and fishing. This reduced the amount of food that we needed to bring along.

On many of the projects that I have been involved with, we hired several helpers from the local village that were also good at hunting and fishing. This reduced the amount of food that we needed to bring along. It is

It is

Being thoughtful in advance can be far less costly than the loss of key gear or equipment by theft, once you are committed to a sampling program.

Being thoughtful in advance can be far less costly than the loss of key gear or equipment by theft, once you are committed to a sampling program.

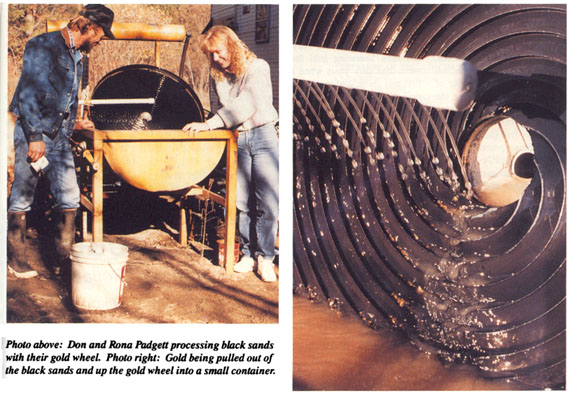

This secrecy-concept also extends to the gold you recover on a mining program. Especially during production! We always set up the final processing structure well away from local traffic, and only allow those near that should or must be involved. The product is

This secrecy-concept also extends to the gold you recover on a mining program. Especially during production! We always set up the final processing structure well away from local traffic, and only allow those near that should or must be involved. The product is  A lot depends upon how inaccessible the project site is. When there are villages nearby, you can sometimes find some local medical assistance for matters that are not of a serious nature.

A lot depends upon how inaccessible the project site is. When there are villages nearby, you can sometimes find some local medical assistance for matters that are not of a serious nature.

A) Accidents: While accidents do happen, they mostly can be avoided by planning things out well in advance and having responsible people involved who are being careful. Good management and responsible people can generally stay a few steps ahead of Murphy’s Law (Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong, at the worst possible time!).

A) Accidents: While accidents do happen, they mostly can be avoided by planning things out well in advance and having responsible people involved who are being careful. Good management and responsible people can generally stay a few steps ahead of Murphy’s Law (Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong, at the worst possible time!). Because we dredge in the water during the sampling phase, it is

Because we dredge in the water during the sampling phase, it is

The best way to avoid continuous problems with sanitation (can be very serious), is to set up your own camp some distance away from local communities and bring in your own cook. This can be someone from the same country who lives in an environment where sanitary-measures are a normal way of life. Then, your cook

The best way to avoid continuous problems with sanitation (can be very serious), is to set up your own camp some distance away from local communities and bring in your own cook. This can be someone from the same country who lives in an environment where sanitary-measures are a normal way of life. Then, your cook  An enthusiastic interpreter will dig for the information that you want to obtain. When communicating with local people on the river, sometimes it is necessary to ask many questions in different ways, to different people, to bring them around to the same concepts that you are trying to express. When you work with people from different cultures who have radically-different backgrounds, often you find that they just do not conceptualize things the same way that you do. A good interpreter is able to bridge this gap and help you get the information you want with some degree of accuracy. He will also help you avoid misconceptions or misunderstandings that can build up stress with locals along the river.

An enthusiastic interpreter will dig for the information that you want to obtain. When communicating with local people on the river, sometimes it is necessary to ask many questions in different ways, to different people, to bring them around to the same concepts that you are trying to express. When you work with people from different cultures who have radically-different backgrounds, often you find that they just do not conceptualize things the same way that you do. A good interpreter is able to bridge this gap and help you get the information you want with some degree of accuracy. He will also help you avoid misconceptions or misunderstandings that can build up stress with locals along the river. Longer-range radios are often used between the base camp and civilization. Although atmospheric conditions sometimes make this mode of communication unreliable.

Longer-range radios are often used between the base camp and civilization. Although atmospheric conditions sometimes make this mode of communication unreliable. I saved this section for last, because it is really the most important. If you study all of the material on this web site, you should realize over and over again that it is the personnel on your project that determine the final outcome. They are the key factor that makes it all happen.

I saved this section for last, because it is really the most important. If you study all of the material on this web site, you should realize over and over again that it is the personnel on your project that determine the final outcome. They are the key factor that makes it all happen. As all gold hunters know, we are blessed with

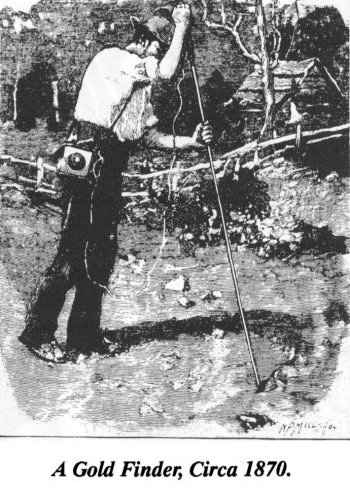

As all gold hunters know, we are blessed with  In 1879, Professor D.E. Hughes demonstrated to the Royal Society in London his Induction Balance (I.B.). Its purpose was to study the molecular structure of metals and alloys. However, Hughes and his instrument maker, William Groves, soon recognized the potential of the I.B. as a metal locator, and several were supplied to various London Hospitals for locating metal objects in human bodies. The Royal Mint used the Induction Balance for assaying metals and detecting forgeries.

In 1879, Professor D.E. Hughes demonstrated to the Royal Society in London his Induction Balance (I.B.). Its purpose was to study the molecular structure of metals and alloys. However, Hughes and his instrument maker, William Groves, soon recognized the potential of the I.B. as a metal locator, and several were supplied to various London Hospitals for locating metal objects in human bodies. The Royal Mint used the Induction Balance for assaying metals and detecting forgeries. This company also developed an underwater spear-type detector which was used in locating gold bars in the wreck of the LAURENTIC, which was torpedoed during World War 1. This was a discriminating-type detector which could distinguish between gold and other metals. Unfortunately, the patent specifications are very brief and no illustrations are enclosed, hence we lack full information of how this detector worked.

This company also developed an underwater spear-type detector which was used in locating gold bars in the wreck of the LAURENTIC, which was torpedoed during World War 1. This was a discriminating-type detector which could distinguish between gold and other metals. Unfortunately, the patent specifications are very brief and no illustrations are enclosed, hence we lack full information of how this detector worked.

Successful mining in streambeds is generally accomplished in two steps: (1)

Successful mining in streambeds is generally accomplished in two steps: (1)

When hard-packed streambed is being mined, the cobbles and boulders (i.e., rocks that are too large to pass through the recovery system) are tossed back onto a pile behind the production area. As the production area moves forward, piles of boulders and cobbles are left behind in place of the original hard-packed streambed. Sometimes, sand, silt and gravel that is processed through the recovery system is dropped on top of the cobbles. Later, winter storms also wash sand, silt and gravel across the top of the cobbles. The sand, silt and light gravel then filters down and fills in most of the space between the cobbles. Therefore, tailings usually end up as loose stacks of cobbles with sand, silt or light gravel filling the spaces.

When hard-packed streambed is being mined, the cobbles and boulders (i.e., rocks that are too large to pass through the recovery system) are tossed back onto a pile behind the production area. As the production area moves forward, piles of boulders and cobbles are left behind in place of the original hard-packed streambed. Sometimes, sand, silt and gravel that is processed through the recovery system is dropped on top of the cobbles. Later, winter storms also wash sand, silt and gravel across the top of the cobbles. The sand, silt and light gravel then filters down and fills in most of the space between the cobbles. Therefore, tailings usually end up as loose stacks of cobbles with sand, silt or light gravel filling the spaces.

Each summer, thousands of prospectors head for the high country in search of

Each summer, thousands of prospectors head for the high country in search of  These elements are Strength, Ability, Flexibility and Endurance. While everyone is born with ability, the other three elements are the things that must be worked on.

These elements are Strength, Ability, Flexibility and Endurance. While everyone is born with ability, the other three elements are the things that must be worked on. The key to finding high-grade gold is in knowing how to

The key to finding high-grade gold is in knowing how to  The mountains have been a home away from home for my family for 100 years. They have seen my grandfather, my dad, and myself enjoy all that they have to offer, providing us with an understanding of what it takes to be responsible and self-reliant.

The mountains have been a home away from home for my family for 100 years. They have seen my grandfather, my dad, and myself enjoy all that they have to offer, providing us with an understanding of what it takes to be responsible and self-reliant. To become a successful gold prospector, research must top your list of things to do. Research will provide you with a never-ending source of future prospects. Experiencing the joy of being in the field, while enjoying these exciting and rewarding activities, should be a major priority for everyone. Furthermore, repeated trips going into the field, being successful, attaining your goals, and coming home with

To become a successful gold prospector, research must top your list of things to do. Research will provide you with a never-ending source of future prospects. Experiencing the joy of being in the field, while enjoying these exciting and rewarding activities, should be a major priority for everyone. Furthermore, repeated trips going into the field, being successful, attaining your goals, and coming home with  The meaning of “Good Gold” is a matter of perspective and experience. This phrase is generally used in terms of quantity and ease of extraction. A couple of old-timers, sitting around the fire talking gold, will often have enough shared-experiences to know what the other means by “good.”

The meaning of “Good Gold” is a matter of perspective and experience. This phrase is generally used in terms of quantity and ease of extraction. A couple of old-timers, sitting around the fire talking gold, will often have enough shared-experiences to know what the other means by “good.” Building a workable dry-washer would be a snap. I have always been good at figuring out how machines work and how they should be constructed. Ten minutes with a friends’ bellows dry-washer was enough to get me started on our own machine. A few days later, we were packed and driving to the desert with our newly-built dry-washer and an old 3-horsepower Briggs and Stratton engine. I just had to test my new creation. When it comes to gold, to me,

Building a workable dry-washer would be a snap. I have always been good at figuring out how machines work and how they should be constructed. Ten minutes with a friends’ bellows dry-washer was enough to get me started on our own machine. A few days later, we were packed and driving to the desert with our newly-built dry-washer and an old 3-horsepower Briggs and Stratton engine. I just had to test my new creation. When it comes to gold, to me,

I have found, to be most effective, it is best to attack a gold-dredging operation with a rigid work schedule, just like any other job or business-activity. I personally prefer to “pour on the steam” for three straight days. Then, I take one day off from dredging to allow my body to recuperate. The work is physically exhausting on the body if you really pour out the energy. You need to find the appropriate rest-interval that works best for you. Otherwise, your body will get overworked and start breaking down. I use my day-off to perform gear maintenance and the many other miscellaneous chores that are needed to keep the operation running smoothly. I try to get some much-needed free time out of it, as well.

I have found, to be most effective, it is best to attack a gold-dredging operation with a rigid work schedule, just like any other job or business-activity. I personally prefer to “pour on the steam” for three straight days. Then, I take one day off from dredging to allow my body to recuperate. The work is physically exhausting on the body if you really pour out the energy. You need to find the appropriate rest-interval that works best for you. Otherwise, your body will get overworked and start breaking down. I use my day-off to perform gear maintenance and the many other miscellaneous chores that are needed to keep the operation running smoothly. I try to get some much-needed free time out of it, as well.

Something we have known for quite some time is that

Something we have known for quite some time is that

Notwithstanding all the excitement and

Notwithstanding all the excitement and  In most cases, the “fast water” you are in is not a steady flow of current. It is usually turbulent, varying in direction and intensity. A swirl can hit you from the side and knock you off balance. Or, sometimes it can even hit you from underneath and lift you out of the dredge-hole and into the faster flow. If you get swept down river in fast water, you usually just need to grab hold of the river bottom and work your way over to the slower water, nearer to the stream bank. This movement is normally best-done by continuing to face upstream, into the current, while you point your head and upper-body towards the river-bottom. That posture will nearly always drive you to the bottom where you can get a handhold on rocks or cobbles to anchor yourself down. Then, you can work your way upstream, through the more slack current near the stream bank, and back out to your work-site again. This is all pretty routine in fast-water dredging.

In most cases, the “fast water” you are in is not a steady flow of current. It is usually turbulent, varying in direction and intensity. A swirl can hit you from the side and knock you off balance. Or, sometimes it can even hit you from underneath and lift you out of the dredge-hole and into the faster flow. If you get swept down river in fast water, you usually just need to grab hold of the river bottom and work your way over to the slower water, nearer to the stream bank. This movement is normally best-done by continuing to face upstream, into the current, while you point your head and upper-body towards the river-bottom. That posture will nearly always drive you to the bottom where you can get a handhold on rocks or cobbles to anchor yourself down. Then, you can work your way upstream, through the more slack current near the stream bank, and back out to your work-site again. This is all pretty routine in fast-water dredging. There is not a single a person among us who won’t panic, given the right (wrong) situation. People who say they will never panic under any circumstances are just not facing reality and, obviously, have never come close to drowning. I believe it is better to understand and acknowledge your limitations before you get into trouble. The closer you cut your safety margin on safety issues, the more aware of your limitations you should be. And, the more important it is to plan in advance how you will react to certain types of emergencies. It is already too late to make such plans the moment something bad happens!

There is not a single a person among us who won’t panic, given the right (wrong) situation. People who say they will never panic under any circumstances are just not facing reality and, obviously, have never come close to drowning. I believe it is better to understand and acknowledge your limitations before you get into trouble. The closer you cut your safety margin on safety issues, the more aware of your limitations you should be. And, the more important it is to plan in advance how you will react to certain types of emergencies. It is already too late to make such plans the moment something bad happens! Other types of underwater vulnerabilities are especially present during fast-water dredging activity. Some of this vulnerability is because it is sometimes necessary to weigh yourself down more-heavily with lead weights to stay on the river bottom. Extra weight is needed to give you the necessary stability and leverage to control the suction hose and nozzle and to move rocks and obstacles out of your way. The demands of dredging activity require divers to be so heavily weighted down, that it is impossible to swim at the surface without first discarding the weights that hold you to the bottom.

Other types of underwater vulnerabilities are especially present during fast-water dredging activity. Some of this vulnerability is because it is sometimes necessary to weigh yourself down more-heavily with lead weights to stay on the river bottom. Extra weight is needed to give you the necessary stability and leverage to control the suction hose and nozzle and to move rocks and obstacles out of your way. The demands of dredging activity require divers to be so heavily weighted down, that it is impossible to swim at the surface without first discarding the weights that hold you to the bottom. When working in fast water, all of your normal safety precautions, preventative maintenance measures, and common sense instincts must be scrupulously observed. Fast water may be thought of as a liquid flow of energy that is constantly challenging you and your equipment. Murphy’s Law (“anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”) is always at work in fast water. It is hard enough to deal with the things that you cannot anticipate will happen. You will have enough of these as it is. But, if you neglect to take action with respect to those things that you can reasonably expect to go wrong, you will almost certainly fail in your efforts to dredge in fast water. If it is wrong, fix it now, before it gets worse!

When working in fast water, all of your normal safety precautions, preventative maintenance measures, and common sense instincts must be scrupulously observed. Fast water may be thought of as a liquid flow of energy that is constantly challenging you and your equipment. Murphy’s Law (“anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”) is always at work in fast water. It is hard enough to deal with the things that you cannot anticipate will happen. You will have enough of these as it is. But, if you neglect to take action with respect to those things that you can reasonably expect to go wrong, you will almost certainly fail in your efforts to dredge in fast water. If it is wrong, fix it now, before it gets worse! Otherwise, if we position the dredge directly in the fast water, it will become necessary for the divers to contend with fast water when entering the water from the dredge. This can be done; but it makes the operation more difficult – especially, when the dredgers need to climb back onto the dredge.

Otherwise, if we position the dredge directly in the fast water, it will become necessary for the divers to contend with fast water when entering the water from the dredge. This can be done; but it makes the operation more difficult – especially, when the dredgers need to climb back onto the dredge. Suction hose support booms are standard equipment on the commercial

Suction hose support booms are standard equipment on the commercial  One of the persistent problems of dredging in fast water is the heavy drag on your air line. This can normally be solved by pulling some slack-line into the dredge hole and anchoring it against the current with a single cobble placed on top. This will allow some slack air line between you and the cobble. You want to be sure that your cobble-anchor is not so large that you cannot quickly free your air line in an emergency. Also, when you leave the dredge hole, don’t forget to first disconnect your air line from your anchor.

One of the persistent problems of dredging in fast water is the heavy drag on your air line. This can normally be solved by pulling some slack-line into the dredge hole and anchoring it against the current with a single cobble placed on top. This will allow some slack air line between you and the cobble. You want to be sure that your cobble-anchor is not so large that you cannot quickly free your air line in an emergency. Also, when you leave the dredge hole, don’t forget to first disconnect your air line from your anchor. You should always keep an eye on your diving buddy while dredging in fast water. When we dive with multiple dredgers on an operation, it is standard policy for us all to keep track of each other. If one person needs to leave the dredge-hole or go to the surface for some reason, he always lets someone know he is leaving. Otherwise, when a diver suddenly disappears, we immediately go looking for him. A person in serious trouble underwater only has about 30 seconds to get it together. This is not much time. What good is diving with someone else for the sake of safely, if you are not paying attention to what is happening with him/her, especially in fast water where there is so very little margin for error? A tender, or anyone else resting at the water’s surface, should be paying close attention without distraction when there are dredgers down working in fast water.

You should always keep an eye on your diving buddy while dredging in fast water. When we dive with multiple dredgers on an operation, it is standard policy for us all to keep track of each other. If one person needs to leave the dredge-hole or go to the surface for some reason, he always lets someone know he is leaving. Otherwise, when a diver suddenly disappears, we immediately go looking for him. A person in serious trouble underwater only has about 30 seconds to get it together. This is not much time. What good is diving with someone else for the sake of safely, if you are not paying attention to what is happening with him/her, especially in fast water where there is so very little margin for error? A tender, or anyone else resting at the water’s surface, should be paying close attention without distraction when there are dredgers down working in fast water. What is fast water? It depends upon the individual. An experienced dredger might be much safer in a typhoon of fast, turbulent water, than an inexperienced person would be in slow, shallow water near the bank. The key for each person is to begin learning in a safe and comfortable environment, gain valuable experience over time, and never attempt to do anything that you cannot easily manage, with safety.

What is fast water? It depends upon the individual. An experienced dredger might be much safer in a typhoon of fast, turbulent water, than an inexperienced person would be in slow, shallow water near the bank. The key for each person is to begin learning in a safe and comfortable environment, gain valuable experience over time, and never attempt to do anything that you cannot easily manage, with safety.